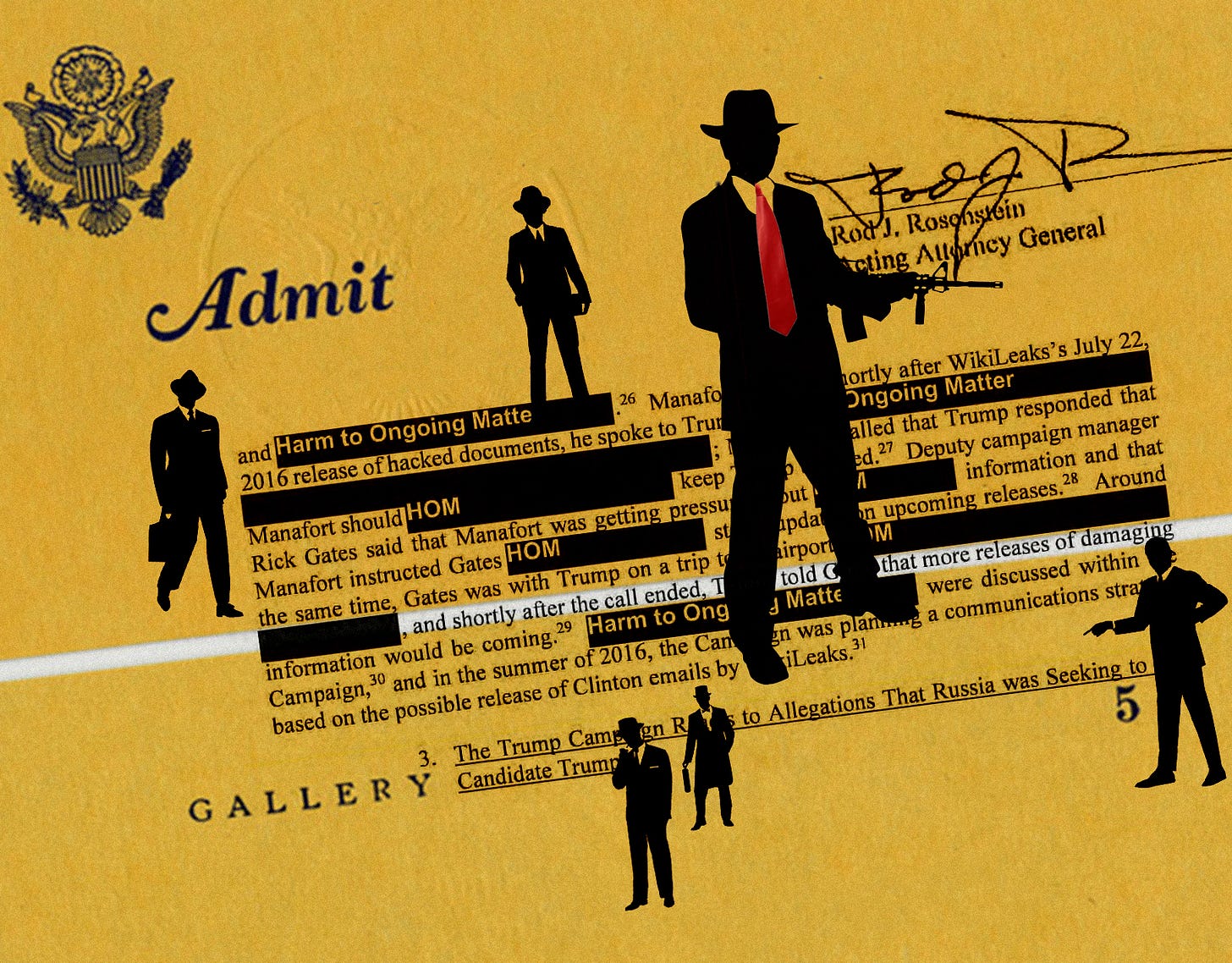

Portrait of the President as a Gangster

The Mueller report reads like the indictment of a mob boss, not an investigation of a president.

Leave aside the collusion, and the obstruction, and the legalism, and the intrigue, and one of the things the Mueller report makes clear is that Donald Trump conducts himself not as a commander in chief, but a mob boss.

The Button Men

One of the recurring themes in the report is Trump reaching out to potential witnesses in ways that are, well, I don’t even want to characterize them. I’ll let Bob Mueller do the talking. When Michael Flynn was under investigation, Trump tried to get Comey to go easy on him by dispatching Christie to butter Comey up:

Towards the end of the lunch, the President brought up Comey and asked if Christie was still friendly with him. Christie said he was. The President told Christie to call Comey and tell him that the President “really like[s] him. Tell him he’s part of the team.” (page 39)

This is merely the first in a series of instances in which the president calls a button-man and has him pass on a message. For example, when Trump is trying to get Jeff Sessions to un-recuse himself from the Russia investigation, he calls a private meeting with Corey Lewandowski—who is not a government employee—and dictates a message to Lewandowski for him to deliver to Sessions. Here’s Mueller:

The President told Lewandowski that Sessions was weak . . . The President then asked Lewandowski to deliver a message to Sessions and said “write this down.” (page 91)

Trump’s message is that Sessions is to give a speech in which he un-recuses himself and then:

The dictated message went on to state that Sessions would meet with the Special Counsel to limit his jurisdiction to future election interference.

Like a good capo, Lewandowski wrote all of this down, but then got a little squirrelly about how to meet Sessions and pass on the message. Here’s Mueller again:

Lewandowski wanted to pass the message to Sessions in person rather than over the phone. He did not want to meet at the Department of Justice because he did not want a public log of his visit and did not want Sessions to have an advantage over him by meeting on what Lewandowski described as Sessions’s turf.

Got that? The president had a message for his own attorney general. So instead of sending an email or picking up a phone, he called in a private citizen and dictated the message to him. This private citizen didn’t want Sessions to be able to record their conversation, or have a witness to it. And he didn’t want any evidence of having met with Sessions. And he didn't want to meet on the other guy's "turf." It gets better. Like most mid-level wiseguys, Lewandowski got cold feet and decided to delegate the job to someone lower in the organization. So he went to Rick Dearborn, at the time a senior White House official. And Lewandowski tasked him with passing the note to Sessions. But—and this is the best part—Lewandowski didn’t tell Dearborn who this message was from. At which point the story goes from good to forking amazing:

The message “definitely raised an eyebrow” for Dearborn, and he recalled not wanting to ask where it came from or think further about doing anything with it. Dearborn also said that being asked to serve as a messenger to Sessions made him uncomfortable. He recalled later telling Lewandowski that he had handled the situation, but he did not actually follow through with delivering the message to Sessions . . . (page 93)

I'm going to fall asleep tonight imagining Robby Mook reading this passage and thinking, "I lost to these guys?"

They Can’t Prove Anything

Here is everything you need to know about Donald Trump’s view of the law in one scene:

The President also asked McGahn in the meeting why he had told Special Counsel’s Office investigators that the President had told him to have the Special Counsel removed. McGahn responded that he had to and these conversations with the President were not protected by attorney-client privilege. The President then asked, “What about these notes? Why do you take notes? Lawyers don’t take notes. I never had a lawyer who took notes.” McGahn responded that he keeps notes because he is a “real lawyer” and explained that notes create a record and are not a bad thing. (page 117)

What sort of man employs lawyers who intentionally don’t keep notes, you might wonder? The same sort of man who does this:

According to Hicks, Kushner said that he wanted to fill the President in on something that had been discovered in documents he was to provide to the congressional committees involving a meeting with him, Manafort, and Trump Jr. Kushner brought a folder of documents to the meeting and tried to show them to the President, but the President stopped Kushner and said he did not want to know about it, shutting the conversation down. (page 100)

Which reminds me a little bit of another family real estate mogul-patriarch.

Always Use a Cutout

The single most striking motif throughout the second volume of Mueller’s report is the extent to which Trump relies on cutouts to exercise his will. He habitually keeps a layer of separation between himself and his decisions. We’ve seen this already with Christie and Lewandowski. But it happens over and over and over. For instance, when Trump decided to fire Jeff Sessions, instead of simply firing Jeff Sessions, he commands Reince Priebus to get Sessions to resign (page 96). Why not just call Sessions himself? After it was revealed in the media that Trump had told Don McGahn to terminate the special counsel, Trump dispatched Rob Porter to request that McGahn write a letter for the record denying that Trump had given that order (page 115). Why wouldn’t Trump make that request of McGahn himself? He was clearly talking to McGahn frequently. Yet even when Trump acts, he often looks to pass the decision off as someone else’s. Consider the firing of James Comey. Mueller reports that Trump decided unilaterally to fire Comey on May 5, 2017 (page 65). He informed McGahn and Priebus of this decision on the morning of May 8 and read to them a letter he had crafted with the help of Stephen Miller that enumerated his reasons for removing Comey:

Dear Director Comey, While I greatly appreciate your informing me, on three separate occasions, that I am not under investigation with respect to the 2016 Presidential Election, please be informed that I, along with members of both political parties, and most importantly, the American Public, have lost faith in you as the Director of the FBI. (page 65)

At 5 p.m. on May 8, Trump held a previously scheduled meeting with Sessions and Rosenstein in which he asked them if they concurred with his decision to fire Comey. They both did, albeit for different reasons than Trump laid out. Trump asked Rosenstein to write a memo summarizing his own reasons for wanting to replace Comey and to have it to him the next morning. Rosenstein did. Comey was fired on May 9. Here is the press release put out by Trump’s White House:

Today, President Donald J. Trump informed FBI Director James Comey that he has been terminated and removed from office. President Trump acted based on the clear recommendations of both Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein and Attorney General Jeff Sessions. (page 69)

This statement is at best misleading and at worst an outright falsehood. But why was it necessary at all? President Trump had the right to fire Comey at any time, for any reason. Why, even here, was he trying to keep an air-gap between himself and his actions? Maybe this is just a passive-aggressive and inefficient management tic. Or maybe it’s a habit of operational security—the way the same guy in a crew never touches both the drugs and the money.

Someday I Will Call Upon You to Do a Service

Let’s not get into legalisms about what is, and is not, criminally actionable witness tampering. Instead, just look at the following examples of Trump’s interactions with people in his orbit and figure out if they seem more like Ronald Reagan or Tony Soprano:

“[T]he President sent private and public messages to Flynn encouraging him to stay strong and conveying that the President still cared about him before he began to cooperate with the government.” (page 131)

“On February 22, 2017, Priebus and Bannon told McFarland that the President wanted her to resign as Deputy National Security Advisor, but they suggested to her that the Administration could make her the ambassador to Singapore. The next day, the President asked Priebus to have McFarland draft an internal email that would confirm that the President did not direct Flynn to call the Russian Ambassador about sanctions.” (page 42)

“In January 2018, Manafort told Gates that he had talked to the President’s personal counsel and they were ‘going to take care of us.’ Manafort told Gates it was stupid to plead, saying that he had been in touch with the president’s personal counsel and repeating that they should 'sit tight' and 'we’ll be taken care of'.” (page 123)

This is not normal in government.

Protect the Don

Trump seems to believe that the executive branch exists not just to serve the president, but to protect him at all costs. Like a bodyguard. Part of Trump’s frustration with Jeff Sessions is that he viewed his attorney general’s recusal as “an act of disloyalty.” (page 108) But the other part is that Trump believed that Sessions’s job was not to administer the laws, but do the president’s bidding:

The President then brought up former Attorneys General Robert Kennedy and Eric Holder and said that they had protected their presidents. The President also pushed back on the DOJ contacts policy, and said words to the effect of, “You’re telling me that Bobby and Jack didn’t talk about investigations? Or Obama didn’t tell Eric Holder who to investigate?” Bannon recalled that the President was as mad as Bannon had ever seen him and that he screamed at McGahn about how weak Sessions was.” (page 51)

Trump even views the heads of his intelligence agencies as his personal minions. He asked Dan Coats, then the director of the Office of National Intelligence, to publicly testify that there was no link between him and Russia. (page 55) He made a similar request of Michael Rogers, the director of the NSA, complaining about how hard the Russia investigation was making his life. NSA Deputy Director Richard Ledgett was present for this conversation and he was pretty freaked out because, again, none of this is even in the same ballpark as “normal”:

Deputy Director of the NSA Richard Ledgett, who was present for the call, said it was the most unusual thing he had experienced in 40 years of government service. After the call concluded, Ledgett prepared a memorandum that he and Rogers both signed documenting the content of the conversation and the President's request, and they placed the memorandum in a safe. (page 56)

My personal favorite, though, is the episode on June 17, 2017, when the president called Don McGahn at his home (page 85). He demanded that McGahn call Rod Rosenstein and insist that Rosenstein fire Mueller. If Trump wanted Mueller gone, of course, he could have called Rosenstein himself. Or simply fired Rosenstein. There was no managerial reason to launder the decision through someone else. The conversation with McGahn is instructive. The president insisted that Mueller had to be fired because he had conflicts of interest:

McGahn was perturbed by the call and did not intend to act on the request. He and other advisors believed the asserted conflicts were “silly” and “not real,” and they had previously communicated that view to the President. McGahn also had made clear to the President that the White House Counsel’s Office should not be involved in any effort to press the issue of conflicts. . . . When the President called McGahn a second time to follow up on the order to call the Department of Justice, McGahn recalled that the President was more direct, saying something like, “Call Rod, tell Rod that Mueller has conflicts and can’t be the Special Counsel.” McGahn recalled the President telling him “Mueller has to go” and “Call me back when you do it.” . . . To end the conversation with the President, McGahn left the President with the impression that McGahn would call Rosenstein. McGahn recalled that he had already said no to the President’s request and he was worn down, so he just wanted to get off the phone. (page 86)

Just picture these last two scenes for a moment. Really picture it: Rogers and Ledgett staring at each other, incredulous at what the commander-in-chief was asking them to do. Don McGahn, sitting in his house, listening to the impossible demands of the president of the United States. These are portraits of men who realize the government is being run by a gangster and do not have any idea what to do about it.