From the Archives: Presidents’ Day Is a Weird Holiday. It Has Been Since the Beginning.

How should a republic honor its leaders?

On February 15, 1798, First Lady Abigail Adams wrote to her sister, outraged. “They are about to celebrate, not the Birth day of the first Majestrate of the union as such, but of General Washingtons Birth day!” Even worse, they had invited President John Adams to attend. Imagine the horror, she sputtered in rage, “The President of the united states to attend the celebration of the birth day in his publick Character, of a private Citizen! for in no other light can General Washington be now considerd.”

The Adamses were right. Celebrating one individual’s birthday was a weird activity for a new republic. Despite Abigail’s protests, celebrations for Washington’s birthday continue to this day, often under the umbrella of Presidents’ Day.

For centuries before John Adams’s presidency, Britons had been celebrating the monarch’s birthday, although the date wasn’t made an official holiday until 1748, under King George III’s grandfather. After declaring independence, most Americans stopped observing this holiday, but felt keenly the loss of the celebration.

By the winter of 1778, Americans had found an alternative. Soldiers encamped at Valley Forge threw celebrations in honor of George Washington’s birthday. The irony was not lost on some observers that Americans who had toasted George III just a few years prior were now shouting rowdy huzzahs for the commander-in-chief of the Continental Army fighting to dethrone the king in the American colonies.

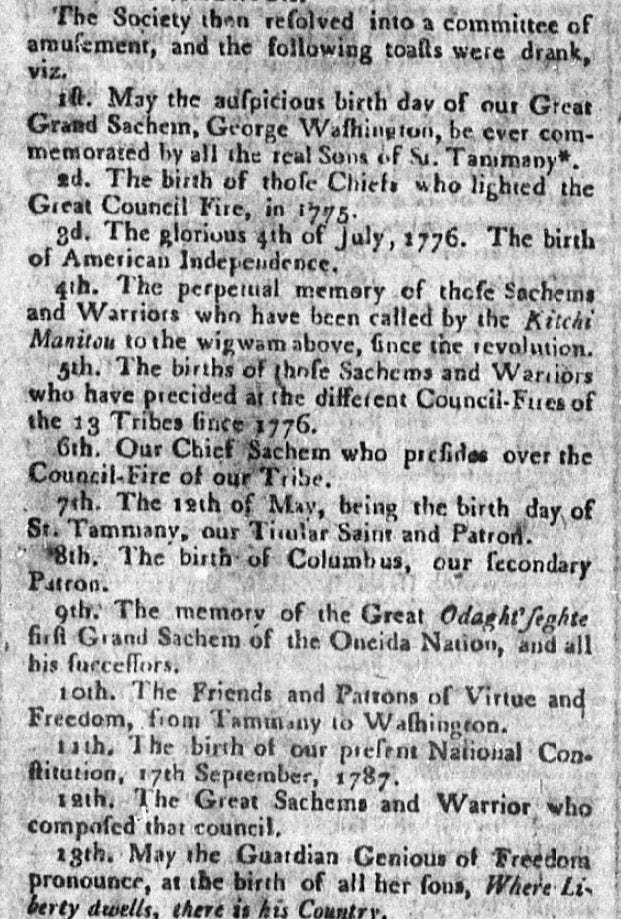

The celebrations continued for the duration of the war and Americans quickly resumed the practice after Washington was inaugurated as the first president of the United States in 1789. For example, on February 22, 1790, ten months into Washington’s presidency, the Society of St. Tammany held an elaborate celebration in New York City, featuring thirteen toasts including “The glorious 4th of July, 1776. The birth of American Independence.”

These observances were not limited to the city of Washington’s residence. Gadsby’s Tavern in Alexandria, Virginia—a town with which he had had a close association for forty years since his days as a surveyor—held an annual birthnight ball in his honor, regardless of whether he was able to attend. Other taverns across the country did likewise.

After Washington retired from the presidency in 1797, these celebrations became more contested as they acquired new meaning. No longer were the commemorations about Washington’s office or the position, but rather a glorification of the person. Washington and Adams’s contemporaries immediately understood the difference and squabbled over the significance.

Adams and his supporters, including his wife, viewed the event on February 22, 1798 at Oillers Hotel as inappropriate for a republic and an insult to the sitting president. Many fans of Washington insisted they were simply recognizing his enormous contributions to the nation. Democratic-Republicans were happy to both criticize the valorization of the first president and gloat over the tensions in the Federalist party.

A few days after the ball, James Madison wrote to Thomas Jefferson, “The late birthnight has certainly sown tares” among the Federalists. “It has winnowed the grain from the chaff. The sincerely Adamites did not go. The Washingtonians went religiously, & took the secession of the others in high dudgeon.”

Although the founding generation disagreed about the propriety of a president’s day celebration, their descendants did not. For the next sixty years, Americans continued to hold Washington birthday celebrations uninterrupted.

After the Civil War and Abraham Lincoln’s assassination, many states added a separate commemoration of the sixteenth president’s birthday as well. By 1940, twenty-nine states had two holidays in February honoring former presidents. Other states, such as Alabama, revealed their preferences and recognized the event instead as Washington and Jefferson’s birthday.

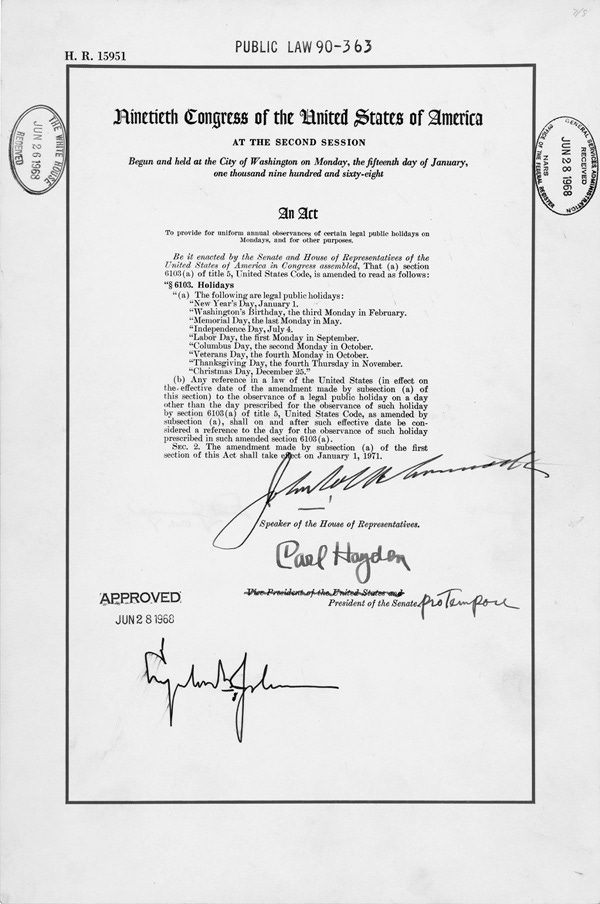

In 1968, Congress passed and Lyndon Johnson signed legislation changing the holiday to the third Monday in February. Ironically, this means that the federal holiday still formally called Washington’s Birthday can mathematically never fall on Washington’s actual birthday—although the choice of date has the happy benefit of always falling between Lincoln’s and Washington’s birthdays (respectively Feb. 12 and 22).

While Congress suggested that the holiday name be changed to Presidents’ Day to honor all presidents, the official name was never changed. But the suggestion stuck after the bill went into effect in 1971. In the popular mind, and in countless commercials advertising sales on mattresses and pickup trucks, the holiday is Presidents’ Day.

But calling the holiday Presidents’ Day, while intended to honor the sacrifices and leadership of our nation’s great chief executives, also honors some of the real duds who have held the office. We honor Millard Fillmore and James Buchanan and Richard Nixon on equal footing with George Washington.

In addition to Washington and Lincoln, the birthdays of a handful of other presidents have been widely celebrated in various ways. Democrats had a long tradition of Jefferson-Jackson dinners in roughly the same season as those two Democratic presidents’ birthdays; the tradition has waned as both men have become more controversial. The equivalent Republican fundraising dinners honor Lincoln and/or Reagan. Also, Franklin Roosevelt’s birthday was, during his years in the White House, celebrated with balls across the country as a way to raise money for the fight against polio.

If we want to take seriously the criticism that respect and gratitude for the office of the presidency are appropriate but that in a republic in which all people are understood to be equal it is not appropriate to revere and celebrate individual presidents, here is a modest proposal.

Perhaps it would make more sense to celebrate great moments of the presidency. Instead of celebrating the birthdays of Washington and Lincoln—dates which, let’s face it, they didn’t really have any say in anyway—maybe we should celebrate the anniversaries of Washington’s resignation as commander-in-chief of the Continental Army and of Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation. It would certainly be more fitting for a republic.