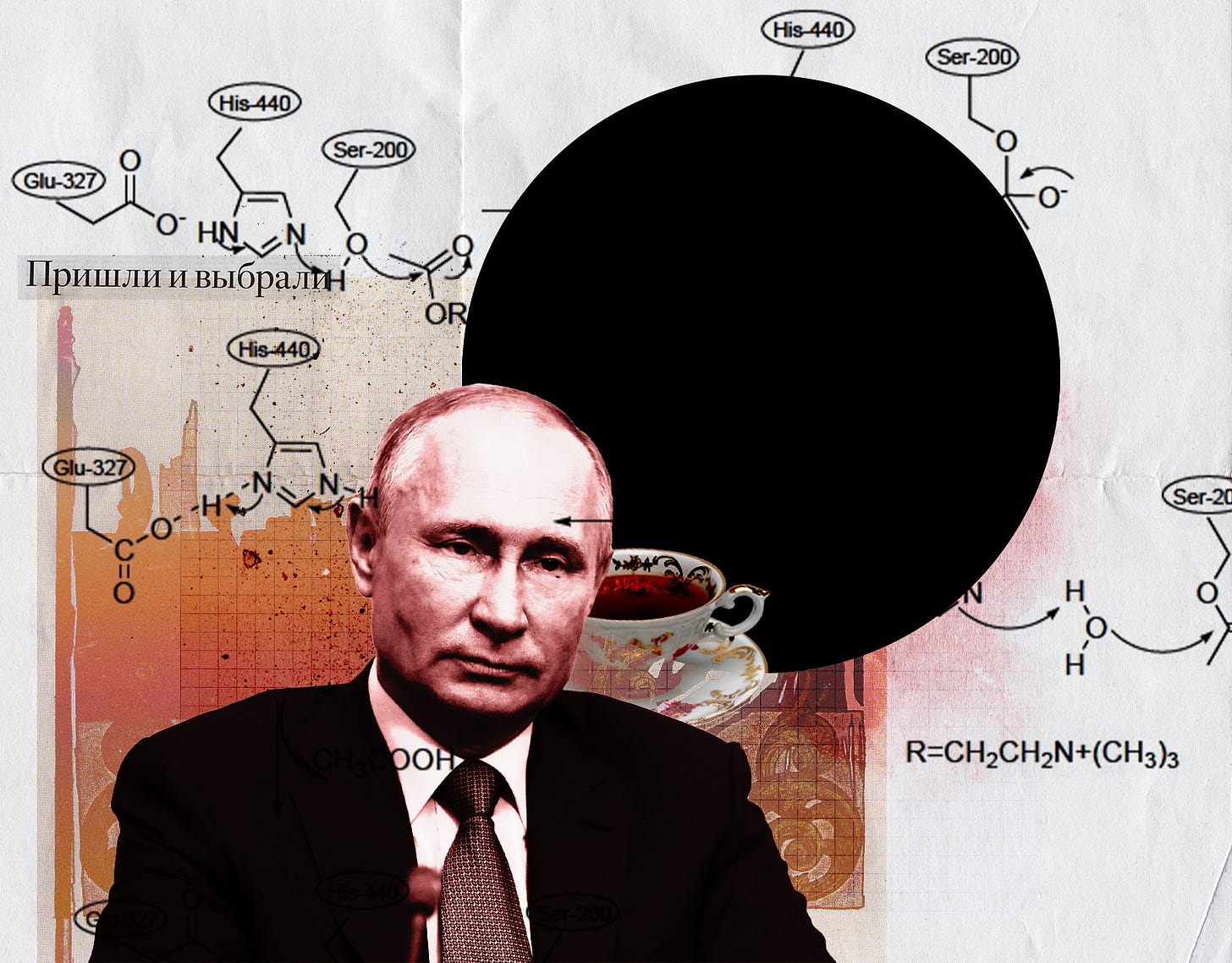

Putin’s Poison

He’s done it again, this time to Alexei Navalny.

Kiev An old Russian joke: “Why did the security services agent cross to the other side of the Tomsk airport terminal?”

Answer: “To poison Alexei Navalny’s tea.”

Navalny is the 44-year old leader of the Russian opposition Progress Party and the most prominent opponent of Russian President Vladimir Putin. Navalny has been arrested and jailed some 13 times by Russian authorities with the international community declaring on each occasion that the charges were fabricated.

During periods that he was incarcerated for his political activism, the Moscow-based Memorial Human Rights Center categorized Navalny as a political prisoner.

This distinction is depressingly ironic since the MHRC was founded in the waning days of the Soviet Union to research and publicize the millions of summary executions, incidences of torture, and other human rights atrocities committed by the secret police apparatus. By documenting and exposing these brutal excesses, the Memorial Human Rights Center had hoped to prevent them from happening again.

Instead, barely a generation later, Russia is run by an alumnus of that same infamous security apparatus.

And torture and murder are back on the menu.

Putin’s apparatus has spared no effort in suppressing public exposure for Navalny. This obsessive urge to eradicate any mention of the opposition leader reached a high point of absurdity in February 2018, a month before Putin’s most recent re-election. Moscow had just been buried in a massive snowfall that was dubbed “the storm of the century,” with many residents becoming frustrated with the slow pace of the municipal snow removal crews.

Muscovites soon discovered that if they simply spray painted Navalny’s name on snowbanks or iced-over roads, then a brigade of snowplows would show up almost immediately. The opposition leader was quoted as saying his “jaw dropped” at how well the prank worked and called the reaction of the city services “state dementia at the service of man.”

On August 20 it became public that Putin’s regime had attempted a more permanent erasure via what has become the former KGB Lt. Col.’s favourite method of eliminating his enemies: poison.

Navalny had travelled to the Siberian cities of Novosibirsk and Tomsk as part of a corruption investigation and to meet with supporters in advance of upcoming local legislative elections. This made the Kremlin nervous, as its preferred candidates have suffered losses in local and regional elections in recent years. (In 2018 the Putin-backed United Russia Governor in Khabarovsk lost in a landslide to a virtual unknown, Sergei Furgal, which was seen as an anti-Putin proxy vote.)

Navalny has long been under 24-hour surveillance, as he told the Financial Times last year: “It’s been going on for quite some time, but I’d be lying if I told you it was routine and we don’t pay attention to it. Some assholes are sitting next to you all the time.”

What is curious is that in the course of this trip, Navalny had been under usual near total blanket surveillance by marked and unmarked vehicles following his movements. And then suddenly, and mysteriously, he wasn’t.

Shortly before Navalny consumed poisoned tea at a Tomsk airport café, the monitoring activity disappeared. Which has—by total coincidence—made it possible for the person or persons responsible for the poisoning to escape identification by the “authorities.”

The implication from anonymous sources within the Russian security services who spoke to the Russian outlet Moskovskiy Komsomolets is that the poisoning was carried out by orders from a higher level—high enough to order a halt to the surveillance net.

Putin’s—and the KGB’s—love of toxins is legendary.

The Soviet-era secret services had a long tradition of exotic methods for murdering persons surreptitiously—most of them involving lethal substances and inventive delivery mechanisms. One of the more such high-profile murders was carried out in the 1970s—in the U.K.—with a poison-tipped umbrella.

These assassination methods were developed in a special secret KGB laboratory—a dark, macabre, real-world version of the British intelligence services spy gadget factory from James Bond movies. Boris Yeltsin, the first post-Soviet era president of the new independent Russia, had the lab mothballed as a gesture of conciliation to the West.

However, his successor, Vladimir Putin, made re-activating the lab one of his first official acts. In early 2000, the man who gave Putin his start in politics, former St. Petersburg mayor Anatoliy Sobchak, became victim number one on what is now a long list of Putin associates and enemies who died (or came close to it) after being poisoned.

This history of murder prompted Russian writer Vikktor Shenderovich to denounce Navalny’s poisoning. “A criminal gang has been in power in the Russian Federation for a long time,” he said on his Facebook account:

The fact that members of this gang willingly use the state symbols of the state they have captured, that they wear tricolour badges, judicial robes, police uniforms, and journalist badges should not distract us from understanding the essence of the matter. The presence of the leader of the gang and his entourage of messianic and imperial hallucinations is an important psychiatric detail, but nothing more. They are deadly to life.

Deadly to life is right. After drinking the poisoned tea, Navalny fell violently ill mid-air. His flight made an emergency landing in Omsk. He was taken off the aircraft and rushed to a nearby hospital where he fell into a coma. A news blackout as to Navalny’s condition descended on the hospital after Russian security agents showed up and told his doctors to stop talking.

A standoff then ensued as an air ambulance aircraft landed in Omsk to ferry Navalny to a Berlin clinic. The aircraft was paid for by a Berlin-based charity and not the German government, but Navalny’s doctors would not release him to be airlifted until the opposition leader’s wife, Yulia, made a personal appeal to Putin himself.

Navalny remains in a coma, but the medical team treating him in Berlin state "the clinical findings indicate intoxication by a substance from the group of active substances called cholinesterase inhibitors." Cholinesterase inhibitors, also known as anti-cholinesterase, are used in several types of medications but also in pesticides and nerve agents.

The chemical blocks an enzyme that controls messages sent from nerves to muscles and leaves the muscles unable to function properly. This affects all major body functions, including breathing. It has all the hallmarks of a product lifted from a highly-sophisticated poison lab’s cookbook.

Navalny may have suffered permanent damage to his nervous system. His doctors now believe he will be out of action for at least two months. Germany, the U.K. and other E.U. members are demanding a full and transparent investigation into this incident. Good luck with that.

As Shenderovich wrote earlier this year, “Russia is a police state, with all the ensuing consequences. The level of state violence will grow: Putin and Co. drove themselves long ago into a dingy corner of illegitimacy, and they simply don’t have an agenda besides their ongoing war with the world, a parade for their subjects and massacre for those who disagree.”

“Deadly to life” in almost every way one can imagine.