Rank Loyalties

Trump’s attacks on the whistleblower and other impeachment witnesses work to collapse the differences between competing kinds of loyalties. It’s the worst kind of moral relativism.

As the House opened the first public impeachment hearings on Tuesday, we’ve already previewed a key line in Trump’s defense: the attempted character assassination of impeachment witnesses. With the president, it’s always a game of loyalties, and if you’re not with him, you’re tainted. The whistleblower is a “partisan hack”; Ambassador Bill Taylor is a “Never Trumper”; and Never Trumpers are “human scum.” The federal government is saturated with dangerous “Obama holdovers” and “career bureaucrats” loyal to the dangerous “administrative state.”

The attacks on Lt. Colonel Alexander Vindman in recent weeks seem to have marked a low point. Vindman is, by all accounts, a man of integrity. He’s a decorated officer, diplomat, and scholar, with a rather incredible immigration story. But for the Trump crowd he’s just another “Never Trumper”—one who, thanks to his having been born elsewhere, they’re also happy to smear as a possible double-agent.

On the whole, these attacks confirm a lot that we already know about Trump and the Republicans who continue to support him—about, for example, their operative paranoia and their cynical reduction of politics to tribal self-interest.

But the smears also reveal and exploit a key vulnerability in our broader political culture: They leverage deep confusions about the very possibility of sound political judgment, and assume that Americans will be unable to form reasonable judgments about different kinds of loyalty. In other words, the attacks demonstrate Republicans’ willingness to kowtow to the same postmodern relativism that they profess to dislike so much.

I’m certainly not the first to point to a connection between Trumpism and postmodernism. (Aaron Hanlon wrote about it in 2018, and Sean Illing does a great job explaining the complicated character of the relationship in this recent piece.) Postmodernism is difficult to define but these days it’s usually deployed to label leftists who question the idea of eternal moral truths and standards. Setting aside the issue of postmodernism’s genuine meaning and value, it’s easy to show how the attacks on the impeachment witnesses are cultivating genuinely nihilistic terrain.

***

The attacks on Lt. Colonel Vindman are useful because they clearly demonstrate the Trumpists’ willingness to flout basic ethical realities. The suggestion that Vindman could be a double-agent taps into ugly nativist impulses, and, as Jacob Levy has shown, relies on the wrong-headed assumption that you can only be loyal to one thing at a time. But we can take it a step further. At bottom, Trump’s attacks presume that there is no meaningful way to judge such matters. His willingness to attack a man such as Vindman implies that there’s no way to discern character—not a record of service, not stated concerns about foreign security and democratic norms, nor corroborating testimony. To attack Vindman is to deny that there are authentic civic norms and truths.

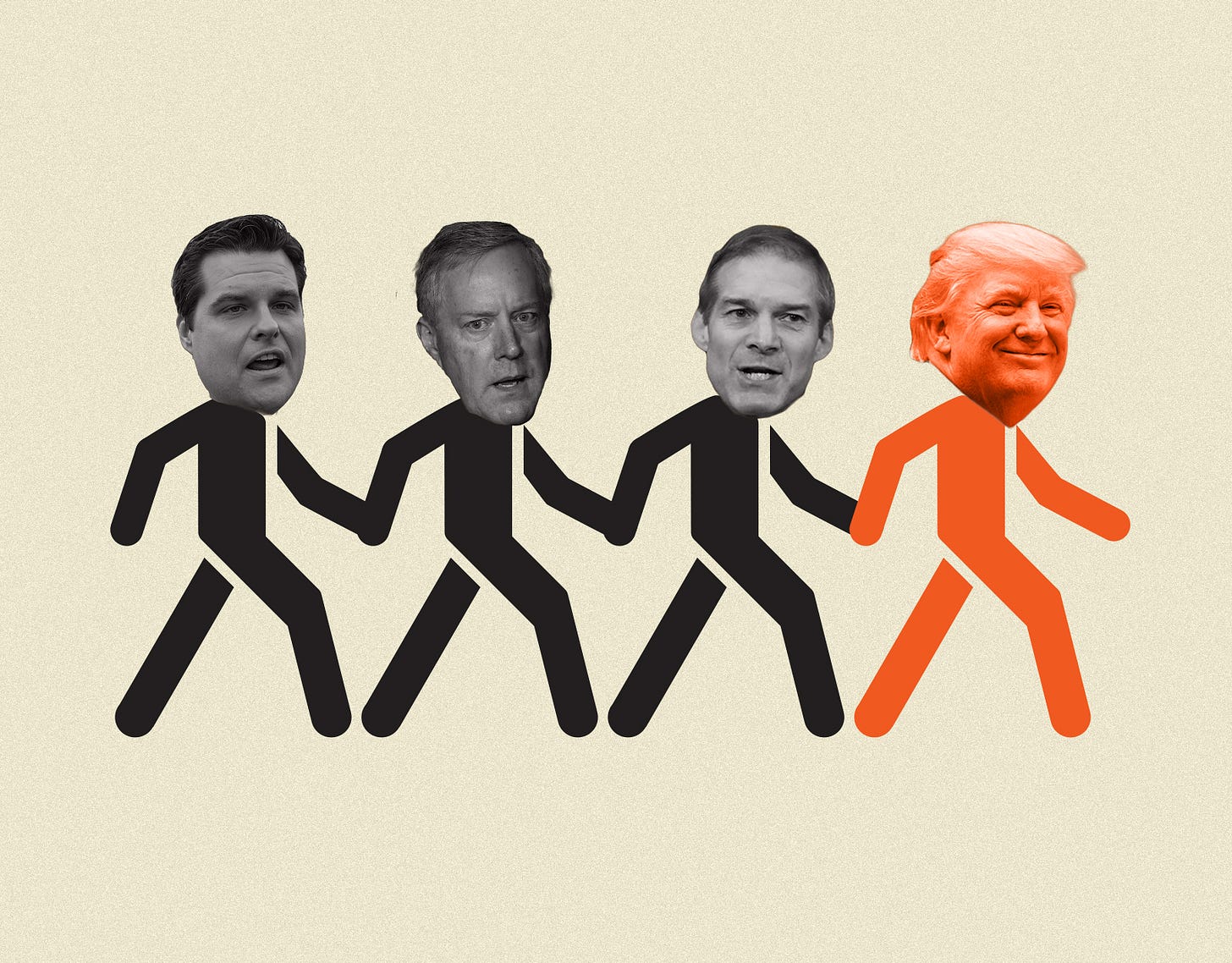

Given Trump’s own character, none of this is surprising. What continues to be surprising is the extent to which the Republican world around him falls in line.

Now, compared to the smears against Vindman, the words used against the whistleblower seem pretty benign (though the same can’t be said of the vicious efforts to expose his/her identity). Among Trumpists, the basic line is that the whistleblower is a “partisan hack job,” connected in some way to Joe Biden. Precisely because this charge is so generic—and therefore transferable—it’s worth looking at more closely.

On the face of it, the “partisan hack” smear is perfectly straightforward. It implies that the whistleblower is someone incapable of professional impartiality because he or she has been overcome by animus for Trump, and/or by love for Democrats. As with the attacks on Vindman, this is actively disinterested in the evidence, and relies on false assumptions about the possibility of plural loyalties.

It also works to conceal the structure and logic of the ideal of professionalism by conveniently ignoring the possibility of an actual “higher calling.”

These days the idea of people having devotions higher than their personal preferences seems quaint. But Trump notwithstanding, it’s still the case in this country that every profession has a set of guiding standards, and that many Americans continue to take such norms seriously. Just this past week, Bill Gates refused to say whether he’d vote for Warren over Trump (“I’m not going to make political declarations”), but he did contend that he’d like to see a “professional approach” in the White House. Doctors take something like the Hippocratic oath, vowing not to disclose the personal lives of their patients. Scientists develop elaborate methods so as not to skew their findings. Insider trading is illegal. In each case, professionals are expected to abide by norms of impartiality that take priority over their personal preferences.

We take such standards for granted, to the point that we sometimes lose sight of their governing purpose(s). The fact is that good professionals sacrifice their personal interests because they care about something else more. Good scientists, for instance, care about the idea of honest research more than they care about the particular outcomes of any given study. And America’s service men and women swear an oath to support and defend the Constitution, regardless of which party controls the apparatus of the federal government. Because they are professionals.

That’s the part the Trumpists want us to forget. They’d rather Americans believe that loyalties all have the same grubbing shape—that it’s inscrutable power-mongering and tax-contriving all the way down.

There’s a chapter in Democracy in America where Tocqueville waxes poetic about, of all things, America’s lawyerly class. He expresses a hope that the country’s lawyers might mitigate tyranny and act as a check on democracy’s excesses, by virtue of their having “made a special study of the laws.” According to Tocqueville, the law inculcates certain “habits of order, a taste for formalities, and a kind of instinctive regard for the regular connection of ideas.” This in turn makes lawyers more sober and deliberative (if somewhat resistant to innovation).

I often thought of that passage in days following Trump’s inauguration, when so many American lawyers made their way to airports to defend the country’s higher ideals in the face of the bigoted Muslim ban.

Today, some three years later, the president faces impeachment. The people called to testify won’t all be lawyers, but they will be civil and military personnel who have dedicated some part of their life to public service. That doesn't make any of them saints. But uncorroborated attacks on these individuals will assume that Americans' political judgment is so clouded and confused that they can no longer conceive of public-minded affinities and devotions.

And, at least in the case of congressional Republicans, it’s not clear that they’ll be wrong.