Release it. Read it.

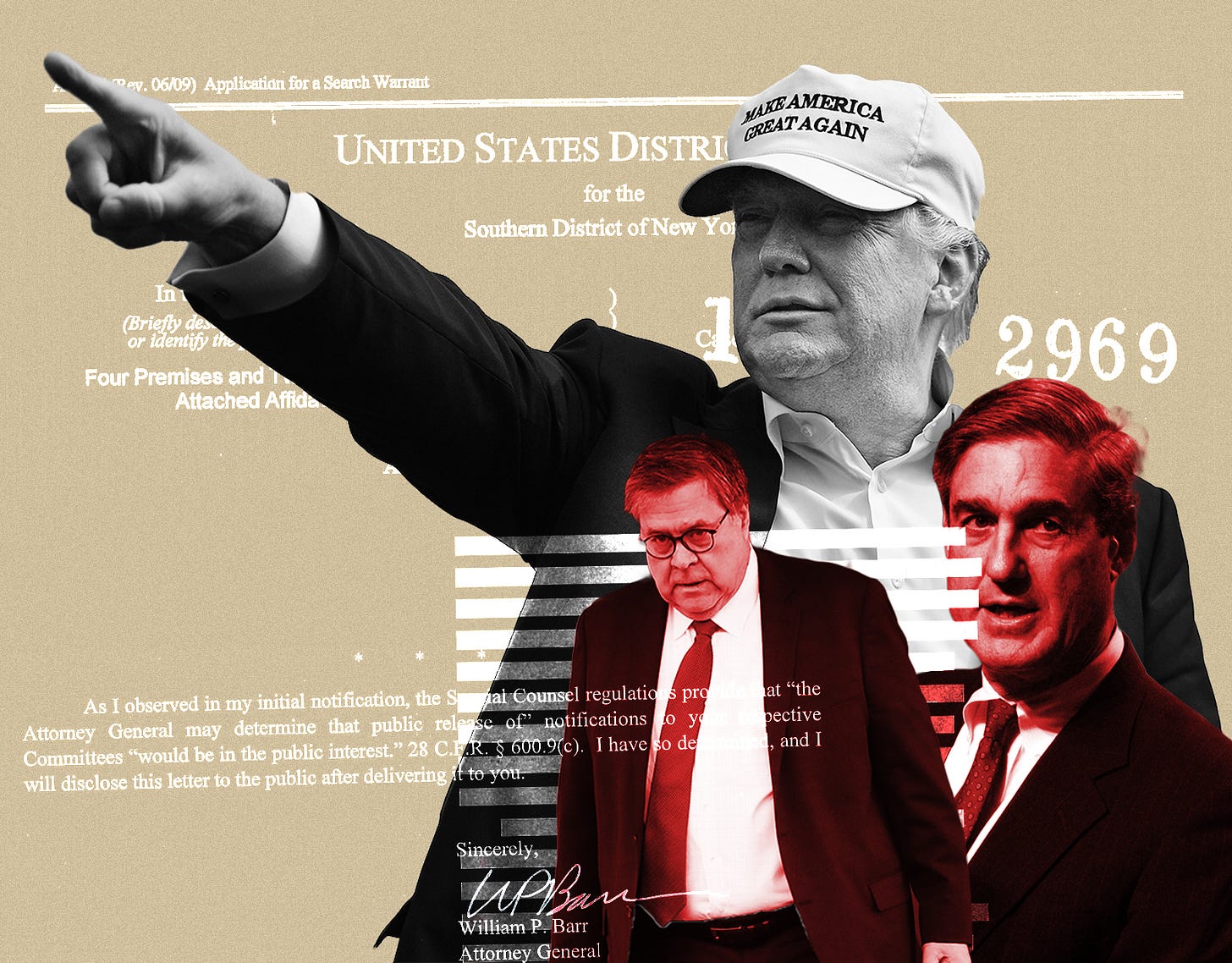

On March 24, Donald Trump tweeted out that The Mueller investigation had resulted in complete exoneration:

On Thursday, when the Department of Justice releases a redacted version of the actual Mueller report, we’ll find out how well that has aged.

President Trump would prefer that we continue to rely on Attorney General William Barr’s perfunctory four-page summary, but the full narrative in the nearly 400-page report will tell a crucially important story. The public needs to know what their president has done and why he has done it.

This is why we think two things must happen: (1) the public needs to read the report thoroughly, carefully, as citizens not as lawyers and (2) Congress must continue to push for the fullest possible transparency.

The roles of the criminal justice system and Congress overlap, but they are nevertheless distinct. Conduct that does not rise to the level of criminal prosecution can nevertheless be inconsistent with constitutional standards of conduct. One need not be indictable to be unfit for high office. The president may use his sweeping powers in ways that do not violate the law, but which constitute an abuse of power. Presidential actions may be legal, but also impeachable.

Mueller did not come to a definitive legal conclusion about whether Donald Trump criminally obstructed justice. But only by reading the report—the full report—will we learn why he deferred the decision. Perhaps his intent all along was for Congress and the public to read the evidence and make that judgment. So now it is quite literally up to us.

It is disturbing that the White House—but not Congress—has received confidential briefings on the full report. Perhaps this explains the palpable level of anxiety coming from Team Trump, which is reportedly bracing for damaging revelations in a report that the president continues to insist completely exonerates him. But if the report includes no evidence of wrongdoing? Why the renewed attacks on Mueller? Why the disquiet among the president’s inner circle?

The full narrative may connect many of the dots already on the public record and could also shed light on much that we only dimly understand, including the president’s odd fascination with currying favor with Vladmir Putin.

This is also why Congress needs to make every effort to see as much of the unredacted report as possible. Barr has said that the redactions in Thursday’s release will be color coded to reflect the various categories of redactions: grand jury material, sensitive intelligence, matters that could affect ongoing investigations, and information infringing on the privacy rights of third parties. Some of those redactions will undoubtedly be both legal and prudent.

But the stakes are high and Congress needs to have as complete a picture as possible of the president’s conduct. Members of Congress routinely see classified material and there is no reason this should be an exception; but Congress should also push for as much transparency as possible within the bounds of the law and reason.

As law professor and Bulwark contributor Kim Wehle has written here:

The grand jury ban on public disclosures is porous. It’s not unthinkable that a federal court—as happened in Watergate and Whitewater—would waive the protections under Rule 6(e) of the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure in the public interest (or alternatively, a coordinated Congress could override or amend that rule).

…

Given the massive historical and political implications at stake, if House Democrats move forward on their threat to subpoena full report, a federal judge might not go along with a Trump appointee’s unilateral redaction decisions. The law allows disclosure of criminal discovery by court order, notwithstanding privacy protections. Ultimately, it will be citizens and their representatives who will determine Donald Trump’s fate. As important as the special counsel’s role has been, it has also been limited. Donald Trump may not face criminal charges (for the time being), but he now has to face the judgment of Congress and the American people.