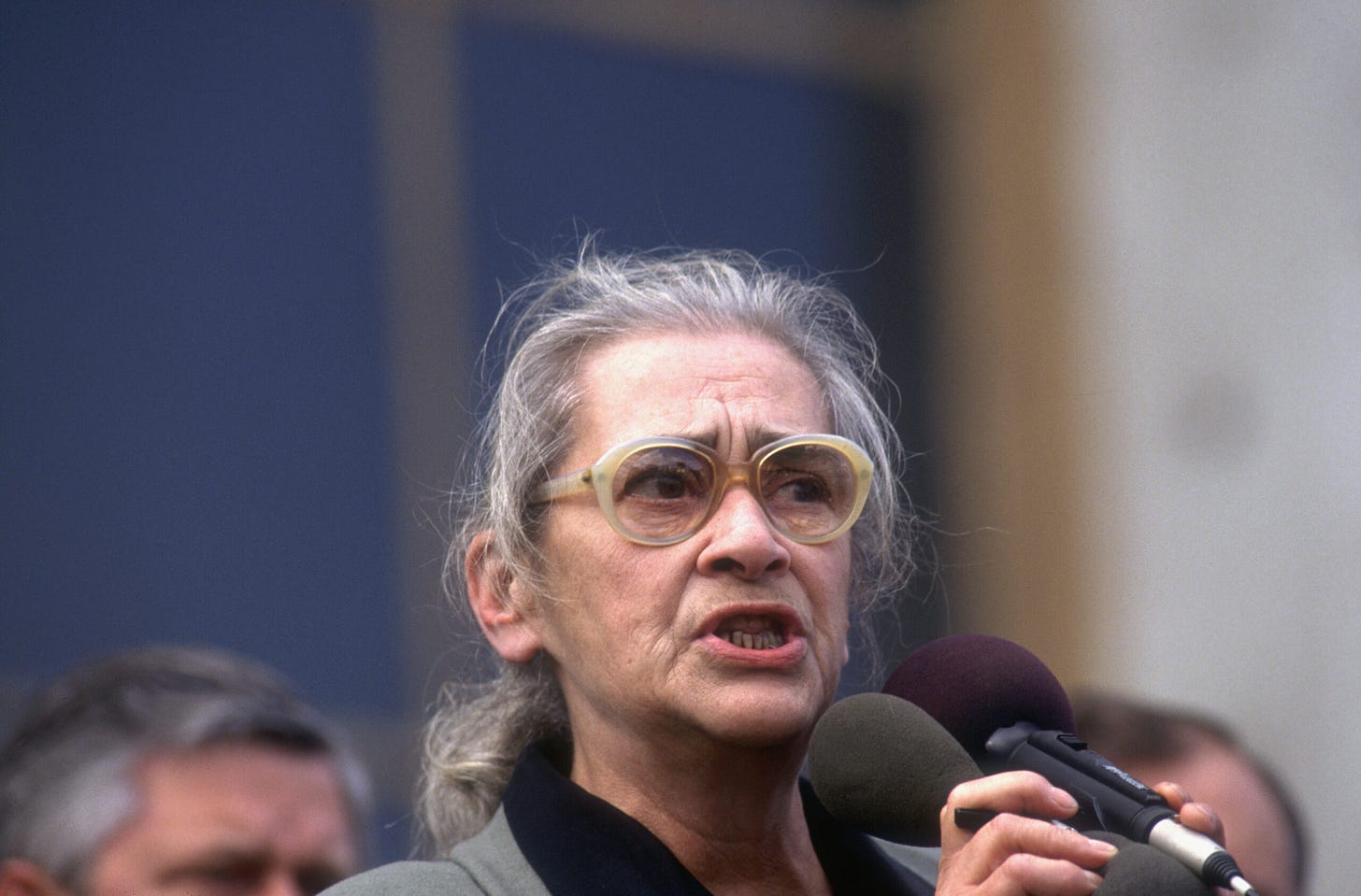

Elena Bonner at 100

The late Soviet dissident was, with her husband Andrei Sakharov, a courageous fighter for liberalism. But what is her legacy in Putin’s Russia?

Last Wednesday, amid the bleak landscape of Moscow in 2023, a building on the edge of a public park near the city center became an island of a very different world, one that still treasures the liberal values of personal and political freedom, intellectual openness, and democratic government. The Sakharov Museum and Public Center hosted a bittersweet celebration of the centenary of a woman whose life embodied those values: Elena Bonner, the widow of the great nuclear physicist, dissident, and human rights activist Andrei Sakharov and a great freedom fighter in her own right. Bonner died in June 2011 at the age of 88; her legacy was never more timely than now.

Bonner was born Lusik Alikhanova in what is now Turkmenistan; both her mother Ruth Bonner and the stepfather who adopted her when she was a baby, Gevork Alikhanyan, were active and devout members of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. (Alikhanyan held a number of high-level Party posts in Armenia and then in Moscow.) Her early years, chronicled in her beautiful 1991 memoir Mothers and Daughters, were privileged by Soviet standards though often made difficult by her stepfather’s absentee parenting and her mother’s emotionally distant tough love. When “Lusya” was 14, it all came crashing down with her parents’ arrest in the 1937 purges; Alikhanyan was executed, Ruth Bonner sent to a labor camp.

Luckily for Bonner, her maternal grandparents saved her and her younger brother from removal to a prison-like orphanage. Yet being the daughter of “enemies of the people” was still a hard lot, made harder by a steely and uncompromising temperament that manifested itself early on. As a teenager, Bonner refused to renounce her parents and was expelled from the Komsomol, the Young Communist League; her first job out of high school was as a cleaning woman. Then came the war. Mobilized to serve as an army nurse at the age of 18, Bonner was badly injured in a bombing that permanently damaged her eyesight; she was also devastated by the death in combat of her former boyfriend and her first love, the young poet Vsevolod Bagritsky. (The loss stayed with her: She helped publish a posthumous collection of Bagritsky’s poems in 1964 and still wept when talking about him in a 2010 interview with Masha Gessen for the Russian online magazine Snob.)

Ironically, army service gave Bonner opportunities that would otherwise have been foreclosed: After the war was over, she was able to get into medical school. Yet in 1953, those opportunities were almost cut off a second time: In the midst of the antisemitic campaign against “rootless cosmopolitanism,” when prominent Jewish doctors were accused of murdering patients as part of a Zionist plot, Bonner was the only student in her class who refused to sign a letter calling for the doctors’ execution. For someone in her position—a woman of part-Jewish descent, a daughter of “enemies” at that—it was practically a suicidal move: she faced certain expulsion from college and likely arrest. Stalin’s death in March 1953 saved her; she got her diploma, became a pediatrician, and later taught in medical school. A gifted writer, she also contributed to several medical and general-interest publications.

In the late 1960s, when the Khrushchev-era “thaw” had given way to an increasingly repressive turn under Leonid Brezhnev, Bonner became involved in human rights activism—a life-changing decision that led to her meeting with Sakharov in 1970, when both were attending the trial of two dissidents in the provincial town of Kaluga. Sakharov had recently lost his wife Klavdia to cancer; Bonner’s marriage to Ivan Semyonov, with whom she had two children, had ended in separation and then divorce.

Two years later, Sakharov and Bonner were married, and their remarkable partnership became one of the great love stories of their time. (It was memorialized in HBO’s 1984 film Sakharov, starring Jason Robards and Glenda Jackson, one of the first works of made-for-cable prestige television—sadly unavailable on either streaming or DVD.) Some believed that Bonner radicalized Sakharov, pushing him from support for democratic socialism and East-West “convergence” to a stronger anti-Soviet, anti-Communist, pro-Western stance. It’s hard to say whether that was the case, but her strength and unflinching support were certainly essential to his work.

As Sakharov became increasingly outspoken on behalf of political prisoners and other persecuted groups, including Jewish activists who fought for the right to emigrate to Israel, he won the admiration of the world—and, in 1975, the Nobel Peace Prize, which Bonner accepted on his behalf because he was barred from foreign travel. Her opening remarks before reading his speech convey her knack for couching her scathing indignation in bitter and understated irony:

I am here today because, due to certain strange characteristics of the country whose citizens my husband and I are, my husband’s presence at the ceremony of the Nobel peace award turned out to be impossible. Today, in fact, he is not here, but in Vilnius, capital of Lithuania, where the scientist Sergei Kovalyov is being tried. Due to those same strange characteristics which made it impossible for Sakharov to be in Oslo, he is at present near the court building, not inside but standing out in the street, in the cold, for the second day, awaiting the sentence against his closest friend.

With the accolades came new hardships. In the late 1970s, as repressions against the dissident movement hardened, Sakharov and Bonner faced increasingly vicious persecution. In 1980, this culminated in internal exile to Gorky (now Nizhny Novgorod), a city off-limits to foreigners 250 miles from Moscow, where Sakharov was deported by a Politburo decree after he denounced the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. At first, Bonner remained officially a free woman; in 1984, she too was confined to Gorky after being convicted of “anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda.” The couple’s isolation was so complete that they were not even allowed a home telephone.

Constant KGB surveillance was compounded by harassment from locals who regarded Sakharov and Bonner as foreign agents, thanks to attacks by the Soviet propaganda machine. Bonner was the target of particularly vile misogynistic and antisemitic smears; blamed for Sakharov’s fall from Soviet grace, she was depicted as not only a domineering wife and a “dissolute” gold-digger but a Zionist temptress who used her sexual wiles to ensnare a naïve widowed scientist and turn him into her puppet. (In a bizarre postscript, the author of one such “exposé” had the nerve to show up on Sakharov’s doorstep in Gorky and ask for an interview for a follow-up; after a brief argument, the usually mild-mannered Sakharov slapped the man’s face.)

During this nearly seven-year ordeal, which Bonner recounted in Alone Together (1986), the spouses were fiercely protective of each other. Bonner remained Sakharov’s lifeline to the world as long as she could; Sakharov’s determination to secure permission for Bonner to travel abroad for essential heart surgery led him to go on a hunger strike and endure brutal force-feeding.

As Mikhail Gorbachev came to power, the winds of change from Moscow blew into Gorky as well. On December 15, 1986, two electricians showed up at the couple’s apartment late at night to install a telephone, accompanied by a KGB man who told them they would get a call the next day. The call came from Gorbachev himself, who said that Sakharov and Bonner could return to Moscow and that Sakharov could resume his “patriotic work.” Tragically, that “patriotic work,” which included membership in the first and only democratically elected Congress of People’s Deputies of the USSR where he was part of the liberal opposition caucus, ended on December 14, 1989. While working on a major speech for the Congress calling for criminal justice reform, Sakharov collapsed in his study with a massive heart attack; when Bonner found him, he was already dead.

It was a devastating loss for Bonner. Yet in the next 22 years, she tirelessly continued the human rights activism that was her and Sakharov’s life’s work. She had already become a major public figure in her own right; in the 1990s and 2000s, her stature only grew as she became an essential if embattled voice for true liberalism.

Bonner supported Boris Yeltsin but resigned from his Human Rights Commission in 1994 because of her objections to the war in Chechnya; a few years later, she was among the first to sound the alarm about the rise of Vladimir Putin. An open letter to George W. Bush which Bonner co-signed with four other Russian dissidents in September 2003, when Bush was about to host Putin in Camp David, feels startlingly prescient twenty years later: Its charges against Putin include not only “war crimes and genocide” (back then it was in Chechnya) but whipping up a “militaristic hysteria similar to Germany under the early Nazi regime.” The letter also accused Putin of destroying independent democratic institutions in Russia and filling key government posts with KGB veterans. It ended with an exhortation to Bush—who had famously declared that he had “looked the man in the eye,” “found him to be very straightforward and trustworthy,” and “was able to get a sense of his soul”—to use the opportunity to take a better look.

Above all, though, Bonner saw her mission in the protection of Sakharov’s legacy. She repeatedly expressed the concern, including in a 2007 interview with me for the Weekly Standard, that after her death the Kremlin regime would try to recast Sakharov as a Russian nationalist, a champion of a strong Russian state and of Russia as a great power. This apprehension was part of what motivated her intensive labor preparing the publication of Sakharov’s diaries along with her own; a three-volume edition appeared in Moscow in 2006.

The last eight years of Bonner’s life were spent mostly in Brookline, Massachusetts near her daughter Tatiana Yankelevich, an independent scholar affiliated with Harvard University’s Davis Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies. (Both of Bonner’s children from her first marriage have lived in the United States since the late 1970s.) She had always had a great affection for the United States; at the end of her trip to the U.S. in the spring of 1986 before returning to exile in Gorky, she wrote a piece titled “A Quirky Farewell to the America” expressing her sympathy for the American dream of homeownership as “a symbol of independence, spiritual and physical.” She never did become a homeowner; but her cozy Brookline apartment with a balcony became her own little corner of the free world, filled with mementoes of her struggle and her life with Sakharov.

Bonner was, by all accounts, not only a remarkably strong-willed woman but a difficult one, a fact I was able to glimpse during our brief acquaintance. (We met two or three times and had several telephone conversations and email exchanges.) She refused to quit smoking, despite several heart surgeries and frail health that left her virtually homebound. She could pronounce harsh judgments. Yet she was also capable of a very genuine warmth: despite her personal and political clashes with Gorbachev, who had berated Sakharov for exceeding his time limit while speaking in Congress the day before his death, she spoke movingly of a telephone conversation she had had with the former Soviet leader after he lost his wife Raisa to cancer and they found a melancholy bond in their common widowhood.

Bonner died of heart failure in 2011, and so did not live to see the 2014 revolution in Ukraine, let alone the insanity of Putin’s war in 2022-2023. But her comments in our conversations in 2007, in person and on the phone, often read as if they were a response to today’s events. She spoke of parallels to Germany in the 1930s: “Putin, like Hitler, is seen as the man who brought Russia out of chaos, raised her from her knees.” She warned about the growth of “a very strong nationalist idea, as well as the idea of Russian Orthodoxy as a state church”:

Authoritarianism, Orthodoxy, populism--not even focused on ‘the people,’ but on ethnic Russians—this formula, which is being more and more broadly adopted by the powers that be, seems to me a very frightening direction for my country. A large part of the population is unhappy about this. But when push comes to shove, even most of those people will not vote for the opposition but for Putin and United Russia, because they’ve been persuaded that the rise in prosperity today is the merit of Putin and United Russia.

While most of her withering scorn was reserved for Putin and his clique, she was also clear-eyed about the fact that the problems that led to the unraveling of Russia’s fledgling democracy—the concentration of power in the executive and the unchecked corruption—began under Yeltsin. So did the pattern of allowing much of the Soviet-era Communist elite to seize power by rebranding as “democrats.” “I didn't think that the Communist elite needed to be tried on criminal charges and sent to Siberia,” Bonner told me. “But they absolutely should have been removed from positions of power, and even from access to jobs in the administration of government.”

Some of Bonner’s harsh criticism was also directed at Western countries, which, she told me, “never truly understood what's going on”: “On the one hand, they are too optimistic; on the other hand, they are mired in an energy crisis, and right now it’s very difficult for European leaders or even for Bush to have a principled position.”

And when we spoke again after Russia’s invasion of Georgia in 2008, Bonner vehemently rejected the notion that the West and the United States in particular were to blame for turning Russia belligerent with its post-Cold War “humiliation.” As she put it: “Russia humiliated itself. It spent seventy-plus years building Communism, and reaped the results.”

Does anything of Bonner’s—or Sakharov’s—legacy remain in Russia today? Bonner’s fear that the Putin-era state would appropriate Sakharov for its own needs came true to some extent, Bonner’s daughter Yankelevich told me in a telephone interview last week. These moves haven’t gone so far as to try to reinvent Sakharov as a Russian nationalist, which would have been too transparently absurd; but the commemorations of his centenary in 2021 focused on his role as a great scientist who had toiled for the glory of the Motherland, with his political and human rights legacy downplayed and erased. Bonner, of course, remains highly inconvenient for such attempts, and so official propaganda has returned to either vilifying her or ignoring her altogether. Just about the only article that marked her centennial in the Kremlin-loyal Russian media—on Stoletiye (“Century”), the website of the Foundation for Historical Perspective—strove for ostensible balance by rebutting claims that Bonner was a Zionist honeytrap, but also depicted her as a foul-tempered bully who probably never loved Sakharov, who despised the Russian people (and loved Israel best), and who had a perverse passion for belittling Russia’s World War II heroism.

Meanwhile, Bonner’s tangible legacy in Russia—the Sakharov Museum and Public Center of which she was the principal founder—is under threat in a climate in which it is likely to be seen as a hostile element. The Center has just lost its lease and will have to either close down or look for other premises, barring an unlikely win in an attempt to legally dispute its eviction. It is perhaps fitting that the current exhibition celebrating Bonner’s life, which will remain open until the end of March, will probably be its last.

“Personally, I’m very, very pessimistic about a future for a civil society in Russia and for independent human rights organizations,” Yankelevich, who spoke by Zoom at the exhibition’s opening on Wednesday, told me by phone. “Still, we have to do what we can, and more. We have no right to despair and to slip into hopelessness. We have to work to enlarge that very slim chance for a turn to the better. Because I know that my mother, however pessimistic or realistic she would have been—she would have continued to work.”

A more bitter valediction for Bonner was provided on the Grani.ru website by Ukrainian journalist Vitaly Portnikov. Bonner, Portnikov wrote, did not merely dream of a different Russia:

She was willing to sacrifice everything for the sake of this different Russia: her health, a normal life, a peaceful old age.

And she lost. No, Russia lost. Russia is that proverbial town without a righteous man of which only a spittle-covered filthy tavern remains. But if someday the filth is washed away and the scoundrels are either expelled or impaled, Bonner will be remembered again—in an instant. Yankelevich, who met Portnikov on a 2017 trip to Ukraine, told me that she emailed him to praise the article—with one quibble. “I wrote, ‘Vitaly, thank you—everything is wonderfully said. Except that I don’t think Mother would have approved of impalement.’”