Republican Lawmakers Might Not Be Able to Handle the Truth, But Kids Can

We owe our children much more than book bans and new restrictions on the teaching of our history.

This month, on her first day in office, Arkansas Governor Sarah Huckabee Sanders issued an executive order banning the teaching of critical race theory in her state’s K-12 public schools. She joined the parade of other mostly Southern Republican lawmakers and governors who have banned teaching CRT in their states’ schools.

Ironies abound in the CRT controversy, starting with the fact that “critical race theory,” properly understood, is an area of academic legal study not actually part of K-12 education. But for the last three years, conservative activists have been using the term as a catch-all for a variety of subjects they don’t want taught in schools.

Which leads to another irony: In some of the states where Republican lawmakers crow about having banned CRT, it is not explicitly defined in the law. For example, in my home state, our governor last year signed legislation with the aim, according to his press release, of “keeping critical race theory out of Mississippi schools.” But the law enacted in Mississippi doesn’t even mention CRT by name.

So what does the Mississippi law do? It forbids forcing students “to personally affirm” that “any sex, race, ethnicity, religion or national origin is inherently superior or inferior or that individuals should be adversely treated on the basis of their sex, ethnicity, religion or national origin.” Which is something no reasonable, decent person can argue with.

Still, talk of banning teaching CRT excites the conservative media complex and the Republican base, who worry that students who study racism in America are being indoctrinated to hate their country.

Meanwhile, liberals worry that these Republican-led Southern states will, while making a show of rooting out left-wing bias in the classroom, limit the teaching of American history in ways that leave students with major gaps in their knowledge of their country’s past, consigning these states to remain among the poorest and most poorly educated in the nation.

Of course, the trick to teaching anything, especially history, is context.

When my young adult novel Sources of Light came out in 2010, I was invited to visit high schools in Arkansas. Set in 1962 Jackson, Mississippi in the civil rights era, Sources of Light is about 14-year-old Samantha, who sees and photographs injustices all around her. She joins marches for voting rights, she becomes involved in the sit-in at Woolworth, and she helps solve the murder of her mother’s close friend at the hands of a racist neighbor. The story is loosely based on my experiences growing up in Jackson during the 1960s and became a way for me to talk with students about the civil rights movement and race.

At the high schools in Arkansas, I showed black and white pictures taken in the 1960s of civil rights marches and sit-ins that helped inspire me to write Sources of Light. The pictures show mostly African Americans marching while white people hold up signs saying things like “Integration is Communism,” “Stop the Race Mixing,” and “Integration is Illegal.” One picture shows a white boy who looks to be 12 holding up a sign that reads “Put Me Down as No [N-word]-Lover.”

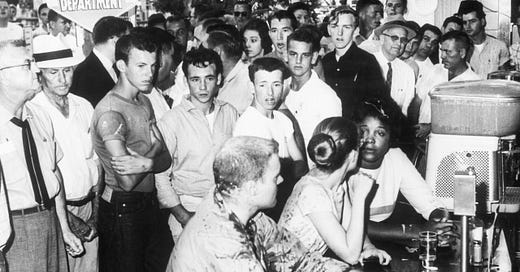

I recall one moment at Central High School when I paused on the iconic photograph of the sit-in at the Woolworth lunch counter in Jackson. I read the passage I wrote in Sources of Light, focusing on that scene where Samantha watches all the white men and boys in the room taunting, cheering, punching, and pouring ketchup, mustard, and sugar on the protesters sitting at the counter.

I asked students to look closely at the photo and choose one person in the group to write from that person’s point of view about what’s happening. The idea was for them to use their imagination to experience or at least consider a different point of view, hopefully helping them to think critically and empathize.

The results were surprising. African-American girls wrote from the point of the view of the white man pouring ketchup on a black man’s head. White girls wrote about the black man sitting at the counter, while one white boy wrote from the point of view of Anne Moody, the black woman at the counter staring at a glass of water. I asked them questions: How does it feel to be that person in this scene? What in your life led you to be there in that moment?

As a white author, I admit, I was petrified talking about the civil rights movement at Central High School, where a group of black students known as the Little Rock Nine enrolled in the formerly all-white school in September 1957. Who was I to tell them anything about the history of this era?

And yet, I was flabbergasted when I discovered how few students knew about sit-ins, the famous anti-violent protest tactic used by civil rights activists. Some of these students were the children or grandchildren of people who had participated in sit-ins or marches in one way or another.

Later, when I asked the teachers about this, they said the same thing: Even though their parents and grandparents had lived through that time, nobody wanted to talk about it anymore. They wanted to move on.

After my talks at Central High School, a student’s mother volunteered to walk me through the impressive Little Rock museum run by the National Park Service. We toured the exhibits together, viewing archival news footage of the Little Rock Nine.

For a long time, we stood in front of that famous photograph of Elizabeth Eckford arriving for her first day of school with a notebook in her hand as a crowd of hostile white students and adults surround her, screaming and spitting on her. We read that they called out for her to be lynched and yelled slogans like “Two, four, six eight, we don’t want to integrate!” As Eckford tried to move forward, one white girl screamed, “Go back to Africa!”

The volunteer mother told me she’d been in the same class with Elizabeth, who often sat alone at lunch and at school assemblies. When the woman, who was white, told me this, she started to cry. She said she was ashamed at how she acted and she didn’t want her children acting the same way.

Here was a woman who lived through a historical moment and regretted her actions. That regret changed her, and she volunteered to host me and other authors to visit schools to teach students about civil rights. This woman’s shame and regret is exactly what Republicans want to avoid in classrooms across the nation.

Decades after she first walked into Little Rock Central High, Elizabeth Eckford said, “True reconciliation can occur only when we honestly acknowledge our painful, but shared past.”

And it’s impossible to acknowledge without knowledge—without knowing. To teach about morality and standing up to injustices, you have to know what the injustice was. And there’s a lot of injustice to be found in history.

Last year, at the Mississippi Book Festival, I attended a discussion about a new book called Blackout. The panel was led by Jackson State University professor Ebony Lumumba, who asked the panel of authors who had contributed to Blackout about their own books, many of which are banned.

Panelist Angie Thomas, author of the 2017 novel The Hate U Give, made an important point: Banning books hurts kids. She had her dog Kobe with her, and even though Kobe jumped and licked her, making everybody laugh, as Angie talked about the consequences of book banning, she started to cry. It was a highly emotional moment.

Angie said she worried for students who wouldn’t be able to read their own stories. They were the ones being cheated. Borrowing a line from Rudine Sims Bishop, the scholar of children’s literature, Angie referred to books as “mirrors, windows, and sliding glass doors”—that is, books can help you better see yourself, help you better see others, or help you better see worlds different from your own.

“Kids that see themselves in my books need those mirrors,” she said.

But there are other kids who need those sliding glass doors and those windows—because when you have young people who see who don’t see lives unlike their own, who don’t understand people unlike themselves. They grow up to be narrow-minded leaders who don’t care about nobody beyond themselves.

The Hate U Give was banned in Angie’s own hometown library in Jackson. In fact, according to the American Library Association, The Hate U Give is among the most banned books in the country, supposedly for “profanity, violence, and because it was thought to promote an anti-police message and indoctrination of a social agenda.”

I suspect the real issue with The Hate U Give is not the swearing or the violence, because those are everywhere in our culture. Rather, the book banners hate the hate in the title, which, lined up correctly on the book’s cover, spells out THUG, a reference to the musician Tupac Shakur’s philosophy: the hate society dishes out might come right back at it.

It is the book banners who are THUGs, and they will reap what they sow. Angie got it right: The hate you give will in the long run become the hate you receive.

While Angie spoke at the panel, a young African American girl from the back of the room walked to the front. She was there to tell Angie how much she loved the book, how she takes the book with her everywhere she goes so she can stop and re-read it. Presumably, she feels a connection with Starr, the main character who witnesses her cousin being shot by police after a traffic stop, a lively, funny, smart, tough, honest heroine who fights her hardest against injustices and things that are just plain wrong. People rub off on you. Characters do, too.

There’s a rule in writing young adult fiction. The young protagonist might get herself into trouble, but she has to get herself out, too. Grownups are mostly background noise and often get in the way.

If I could write that moment with Angie and her reader, the girl saves herself just by reading a banned book.

Angie signed that girl’s book, still fighting through tears.

For the last five years, I’ve had the privilege of serving as a judge for the National Scholastic Writing Contest, an annual award competition for students in seventh through twelfth grades. I read essays from Indiana students, judging on content, style, originality, and voice.

In the past, these students mostly wrote about divorce; sibling rivalry; having a best friend; breaking up with a best friend; moving; cooking; sports; the loss of a family member, friend, or pet; eating; not eating; feeling too fat; feeling too thin; and failing or excelling in school.

In recent years, I’ve read more and more essays about loneliness, suicide, school shootings, and depression. This year’s batch felt significantly different.

Here were younger students wrestling with major depression. They were frustrated with the mindlessness of virtual learning. Many had no one to talk to. They wrote about domestic abuse, reconsidering one’s gender, dealing with an unwanted pregnancy, figuring out reasons to live, being deported as a new immigrant, racism, and coming out to their parents. They also wrote about getting COVID and surviving a shooting.

These students were grappling with life’s biggest challenges, often involving life or death.

This year, when I finished reading these essays, I wanted to write back to each student to tell them It’s all right, you’re going to be fine. But then I read the newspapers and I’m not so sure. Recent studies show that, even before the pandemic, teen depression was up, roughly doubling from 2009 to 2019, and so was the adolescent suicide rate. There are new viruses, increased poverty, extensive climate damage, more school shootings, and politicians are focusing on . . . CRT and book bans?

How are students supposed to learn how to deal with these weighty subjects if they can’t read about them—and read about them from different perspectives? The solution is not to take away the books that might address these issues.

We shouldn’t be afraid of students reading whatever books they can read and learning all the history they can learn. Studies show that the more you read and write, the less likely you are to go to prison and the more likely you are to finish high school, graduate from college, get a job, and volunteer in your community. Young readers are also more likely to vote—and chances are they will be better informed voters because they read and think critically.

The best young writers in the contests I judge clearly sense form and structure, and I like to think that if they know what makes good writing, they will know how to shape their lives. I give these students a lot of credit for just sitting down and mulling over complex and deeply personal subjects, topics many adults spend a lifetime avoiding.

They inspire me.

I wish the book banners and the anti-CRT folk could read these student essays and see for themselves how young people process, understand, and, often, overcome life’s traumas and injustices.

But then, they’d probably ban them.