Ridley Scott’s Dyspeptic Disposition

The 84-year-old director is a charming curmudgeon.

No one would have confused Ridley Scott for an optimist in those early years.

The Duellists in 1977 may have earned him critical praise, but it was Alien two years later that brought him to the public eye. A horror movie about truckers in space whose lives mean less to the corporation for which they work than the possibility of transporting extraterrestrial life back to Earth, Alien keyed in on a number of latent terrors at the heart of the era of malaise in which it was made. In space, no one can hear you scream; in the boardroom, they might be able to hear you, but they certainly don’t care.

Blade Runner (1982) was only slightly more positive about human nature, and even then only because it shrugged off the idea that being “human,” as opposed to “replicant,” really mattered all that much so long as you understood yourself to be real. “It’s too bad she won’t live,” one character says to another who has fallen in love with an android. “But then again, who does?”

It was an advertisement, though, that really cemented the whole dystopian vibe Scott was striving for, a reimagining of Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four for the PC age in which a Mac user smashes the hegemonic face of DOS and brings freedom to the masses. That this band of outsiders would come to be the dominant force in home and mobile computing with the biggest market cap in the world is not an irony that should be lost on us.

Scott’s dyspeptic side has been on display in recent weeks; when he’s not railing against millennials and their damn phones he’s highlighting the fact that Hollywood’s structural incentives are lined up against the sort of picture he’s spent his career making, namely adult fare with a decent budget. That this second point is distilled to, and I’m paraphrasing, “Ridley Scott versus comic book movies” only underscores his general thesis.

I don’t think it’s fair to say that Scott takes a dim view of humanity, per se; he is, after all, the director of The Martian, a testament to human ingenuity, and there’s more genuine brotherhood and humanity in any 30 minutes of Black Hawk Down than there is in most directors’ entire careers. But he certainly takes a dim view of institutions and the ways they reflect or magnify the failings of the humans that comprise them. In both films the 84-year-old Brit released this year, human institutions come in for a beating.

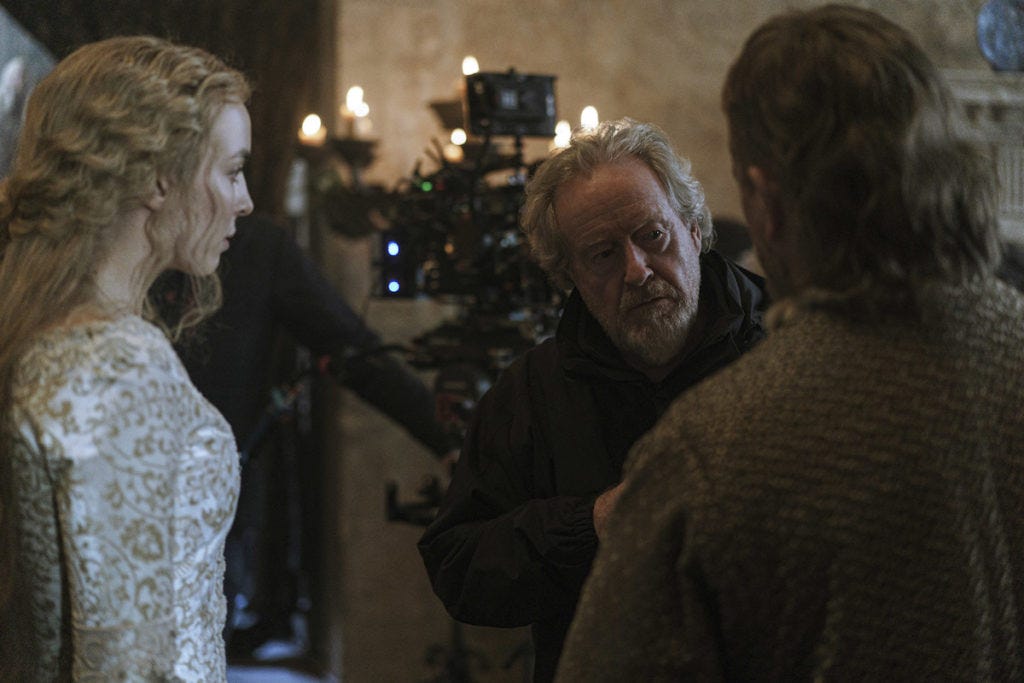

You see it in The Last Duel, a movie that gives us the point of view of three different participants in a political institution. As distant as 14th-century France may seem from our own time, its rules and regulations aren’t so very different from ours. That’s what we learn as we watch a king and his court—and the courts—denigrate Marguerite de Carrouges (Jodie Comer) after she accuses Jacques Le Gris (Adam Driver) of raping her while her husband Jean (Matt Damon) was away on business. Jacques thought he was playing the game of seduction and that Marguerite’s protestations were pro forma; the courts thought they were merely doing their duty as they pried into her personal life and insinuated that her resultant pregnancy meant that she enjoyed the encounter; Jean thought he was defending not only her honor but his own, which was in short supply following repeated humiliations at the hands of Count Pierre d’Alençon (Ben Affleck).

The Last Duel is, as I’ve written elsewhere, surprisingly funny for a movie that revolves around a rape and its aftermath, the humor derived from the absurdity of nearly all involved. Ridley Scott’s latest, House of Gucci, desperately strives for the same sort of absurdity—a mood best embodied by the over-the-top performance of Paolo Gucci by Jared Leto, the actor who seems to most understand the ridiculousness of the situation—but falls flat.

Gucci follows the efforts of Patrizia Reggiani (Lady Gaga) to become part of the famed Italian fashion house; she meets Maurizio Gucci (Adam Driver) at a party, seduces him, and the two marry over the protestations of father Rodolfo (Jeremy Irons). Uncle Aldo (Al Pacino) is a bit more forgiving, however, having sired only the idiot Paolo whose garish runway fashions are blindingly ugly and a blight on the family name.

And the family name is what matters here, Gucci being a family business and all. It’s the family Patrizia tries to work her way through, tries to insinuate herself within, tries to get Maurizio to betray and abandon. If family is an institution—in this case one of maniacs, several of whom seem to belong in a literal institution—then the Gucci foundations are crumbling, cracks in the façade becoming clearer and clearer to everyone on the outside even as those on the inside squabble over the falling walls.

I try not to get mad about stupid people saying idiotic things, but I was terribly vexed when someone on Twitter made the absolutely idiotic claim that Ridley Scott hadn’t made a good film in 40 years. Has he had some fallow stretches and a handful of stinkers (House of Gucci among them, sadly)? Sure. That said, any body of work that includes Thelma and Louise and White Squall and Black Hawk Down and Gladiator and Matchstick Men and American Gangster would be solid enough on its own.

And I would put any director’s work after the age of 75 up against what Scott has done for the last decade, Clint Eastwood included. Over the last week or so I’ve been revisiting Scott’s work with Michael Fassbender—Prometheus(2012), The Counselor (2013), and Alien Covenant (2017)—and I’ve again been struck by just how down he is on humanity, still, after all these years.

Prometheus and Alien: Covenant are nominally prequels to his first big hit, Alien, but they are more properly understood as ruminations on whence we come and where we’re going after we’re gone. David (Fassbender) is an android assigned to the Prometheus, a spaceship on a mission to find a mysterious race of alien “engineers” that created humanity. He knows his maker (Peter Weyland of the Weyland-Yutani corporation) and knows that his maker and his maker’s daughter and even his maker’s underlings have nothing but disdain for him, a disdain that poisons him against mankind in general. That disdain will manifest, cataclysmically, in Alien: Covenant, and while we’re all aghast at what David does it’s hard not to understand how, exactly, he wound up on this nihilistic path.

Scott has intimated that Prometheus and Covenant make up two-thirds of a “David Trilogy,” with a third and final installment coming sometime in the future if he can scrounge up the budget. Perhaps. But I like to think the trilogy has already been completed, that The Counselor served as a bridge of sorts between the two. In that film, scripted by world-champion misanthrope Cormac McCarthy, Fassbender plays a nameless lawyer. (Nameless to us, the viewer; who’s to say that his name isn’t David?) This counselor gets caught up in a deadly game when a deal with the Mexican cartels goes bad.

This counselor pays for his mistake—but not with his own life.

I say I like to think of it as the second movie in the David Trilogy because it could very easily be taken as the film in which David learns why humanity is irredeemable, why they must not be allowed to spread through the galaxy. Why they deserve to be fodder for face huggers and nothing more. The Counselor is a remorseless movie. Not cruel, though certainly lacking in empathy. But mechanical, choking. The plot operates like a bolito, the mechanical necktie that serves as an execution device in the film, its metal alloy loop drawing ever tighter until it severs first the carotid artery of the victim and then his head from his shoulders. The counselor puts a bolito around his own neck without even knowing he’s done so. We watch as it separates him from everything he loves.

Hollywood’s bolito is the superhero movie and you can understand why Scott might be a bit down about his preferred milieu’s future. The Last Duel was well reviewed but a box office disaster; House of Gucci is doing better with audiences but is unlikely to outgross the first three days of any Marvel-branded movie released this year. Adult dramas are out of vogue because people only want to see big-budget spectacle, which ensures that resources increase for big-budget spectacle, which reinforces to audiences that adult dramas are not made for multiplexes, which in turn decreases resources for them. It’s a vicious cycle, self-reinforcing, closing with mechanical precision.

Scott will continue to work. For the big screen, he is filming a movie starring Joaquin Phoenix as Napoleon. On the small screen he remains a prolific producer and occasional director, and the projects are generally interesting (I’m still waiting on seasons two of Taboo and Raised by Wolves). A number of future Scott projects have been announced, but this is a guy whose list of announced-but-never completed projects is legendary. Who knows what the future will bring. But it would be a shame if his feelings of discouragement about moviemaking and millennials were to mean that his time as one of the last of the big-budget filmmakers for adults is drawing to a close.