Should We Be More Skeptical of the ‘Digital Future’ After the COVID Experience?

It’s not just about what our machines can do. It’s about the kind of beings we are and the kind of society we want to live in.

The Future Is Analog How to Create a More Human World by David Sax PublicAffairs, 273 pp., $29

The Future Is Analog is a quirky and fascinating book. Really, it’s two books. The first is a sequel of sorts to one of David Sax’s earlier books, The Revenge of Analog (2016), which featured, among other things, a visit to a record-pressing plant (vinyl records, that is). The second is a reaction to the COVID-19 pandemic as a society-wide experiment in replacing real life with digital facsimiles: school, work, church, entertainment.

The “analog” in the title, which in the earlier book nodded to the curious phenomenon of people rediscovering obsolete but wonderfully tactile technology, has been expanded here to simply mean “not digital.” Real-life conversation becomes “analog conversation”; what we used to call “school” becomes “analog schooling.” On the one hand, Sax applies a unique framing to analyzing why living life in-person matters; on the other hand, his “analog” analogy is so broad as to lose some of that analytical insight. “Analog” here is not an aesthetic, but a set of values, an approach to life.

This is an entertaining book; Sax is no dour traditionalist. He refers to Mark Zuckerberg’s Metaverse as “animated bullshit,” and proposes exactly what Mr. Zuckerburg can do with it. He encapsulates the aggravation of supervising “remote schooling” by recounting a morning when his son, late to virtual school, was instead dancing in the bathroom repeatedly singing “I’m a penis!”

But The Future is Analog is mostly serious, even furious. And it is best understood as a pandemic book: a full-throated defense of physical, tactile, in-person, “analog” reality. Indeed, it could have been titled “Against the New Normal.” Sax is a self-identified Canadian Jewish liberal, yet at times he sounds rather like American conservatives in his critiques of pandemic-era (and, for many people, post-pandemic-era) life. “Staying at home forever isn’t a victory for digital; it’s a failure of imagination,” he writes. Or, “We are flesh-and-blood creatures, bound by biology and all its quirks, and we experience life in all its richness, risk, beauty, and misery.” Digital life, mediated and shaped and fed to us by corporations and coders and their algorithms, robs life of that richness.

So beyond merely inveighing against the new normal, Sax argues that lockdown was the closest we've ever gotten to the ballyhooed “digital future.” It was a chance to test drive claims that Silicon Valley had been making for decades. And as such, it was a preview of what that digital future would look and feel like if it ever really arrived. In short? It sucked.

Now a book like this is necessarily very subjective. Everybody experienced the pandemic differently (and many in circumstances far more difficult than Sax’s). Surely many people, including many of Sax’s readers, found things to like in this preview of our digital future. But a simple question can help determine whether Sax is merely stating his own preferences or noticing something real: Do his claims ring true? Or do they seem overstated or even contrived?

“Each task was just another interaction on the same three screens: phone, laptop, TV.” Feels true.

The Netflix queue is like “a buffet that gets more unappetizing the longer you stare at it.” Yeah, feels true too.

Getting outside involves “beautiful discomfort,” a kind of good friction. Yep.

A quote from one of his interviewees: “No one remembers their best day of watching TV.” Damn.

There are many more such observations, many of which put into words the unease I felt, and heard about from others, in the period Sax is talking about.

Underneath Sax’s descriptions of the frustration, boredom, loneliness, and mental disquiet of pandemic life there is an almost metaphysical critique, an argument that something about digital technology just doesn’t quite jibe with our humanity. (This deep critique is reminiscent of the old claim that vinyl records sound or feel warm, in some immeasurable but real way.) As if feeding our analog brains a digital diet is something like feeding beef cattle corn; it works in a limited way, but it causes side effects and discomfort. What we perceived merely as discomfort or frustration was perhaps evidence instead of some fundamental incompatibility.

Sax speaks to experts who, for example, argue that there really is something about videoconferencing that causes boredom, headaches, and that indescribable unease. In other words, it isn’t just a feeling. It is a stress response. Or who discuss how a sense of time and structure is important to our mental health. Spending eight hours at a computer in your pajamas isn’t just slobbish. It robs our brains of color, texture, friction. The changing of settings and places, the inconvenience of commuting, the physical discomfort of the weather; they can all spark creativity or give our brains a rest. Digital life, on the other hand, is simplified and flattened. It can be comfortable physically yet uncomfortable psychically and, in the long run, physiologically. Sometimes, if something doesn’t make you happy, it’s bad.

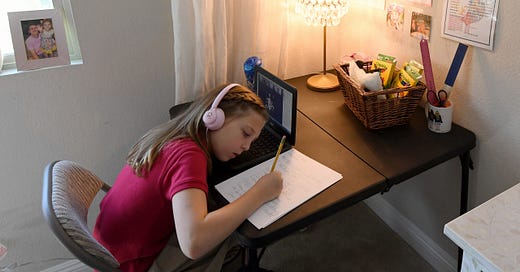

Sax’s book is structured as a “week,” with each chapter a day: work, school, rest, and so on. Particularly harsh is his critique of remote schooling—one of the few pandemic-era policies to be derided by both conservatives and many liberals. His chapter on work is bearish on working from home as a long-term trend, and observes that the friction of commuting can be productive. His chapter on cities and urban life mostly celebrates street life and small business and critiques the “smart city” and restaurant delivery apps. Sax’s “analog” framing permits a whole cavalcade of social critiques to reside comfortably in the same book.

Other than the school chapter, which is probably the strongest, the other really notable chapter is “soul,” on religion and spirituality. And it is probably the weakest. For many Americans, the closure of churches was a central storyline of the pandemic, and arguably one of the key policies that turned right-leaning opinion against the entire idea of public health. Yet Sax frames the closure of houses of worship more as a lifestyle question. He does push back on the breezy attitude of “Why go to service in person when I can livestream it?” Yet most critics of church closures were fighting not their own desire to stay home, but policies preventing them from going when they desperately wanted to. For a book so critical of lockdown life, this is a curious omission.

Other than Sax’s own Judaism, there may be no religion more “analog” than old-fashioned Catholicism, which engages every sense. Bells, candles, incense, kneeling, singing, striking the chest, more kneeling, not to mention the sharing of the Eucharist. Yet for his main example drawn from the Christian tradition, Sax goes to pretty much the polar opposite, talking with a Unitarian Universalist pastor, who mostly offers bromides about community and collective action. Sax notes that young people were among the most enthusiastic to return to in-person worship; here again, one wishes he dug more into the phenomenon, or into the larger set of objections to the “digital future” among the religiously devout.

And that raises another thought, though not a critique. Sax’s whole book only makes sense for those who did in fact go through lockdowns, the extended post-lockdown period of caution, and the turn to digital-everything. For those who work with their hands—or for those who pulled their kids out of shuttered public schools, moved to “freer” states, or continued to hold weddings, funerals, and holiday dinners—The Future Is Analog will read like a dispatch from an alien planet. Whatever can be said about such pandemic objectors—much of it not flattering—it is at least true that they do not need to be reminded of the centrality of real, in-person gatherings, school, or worship.

Sax does not address any of this, nor does he actually criticize public health measures, despite critiquing their effects and realities.

In the end, this does-he-or-doesn’t-he makes it possible to enjoy The Future Is Analog no matter what you actually thought about the wisdom of lockdowns or the various pandemic-era public health policies. Because we can all agree that living through them sucked, and that while the convenience of doing many things on screens is worth appreciating, doing everything on a screen creates all kinds of misery. In the long run, life is better lived in the physical, analog world.