Strong Signals of Support for Liberal Democracy Abroad from Newly Elected Czech President

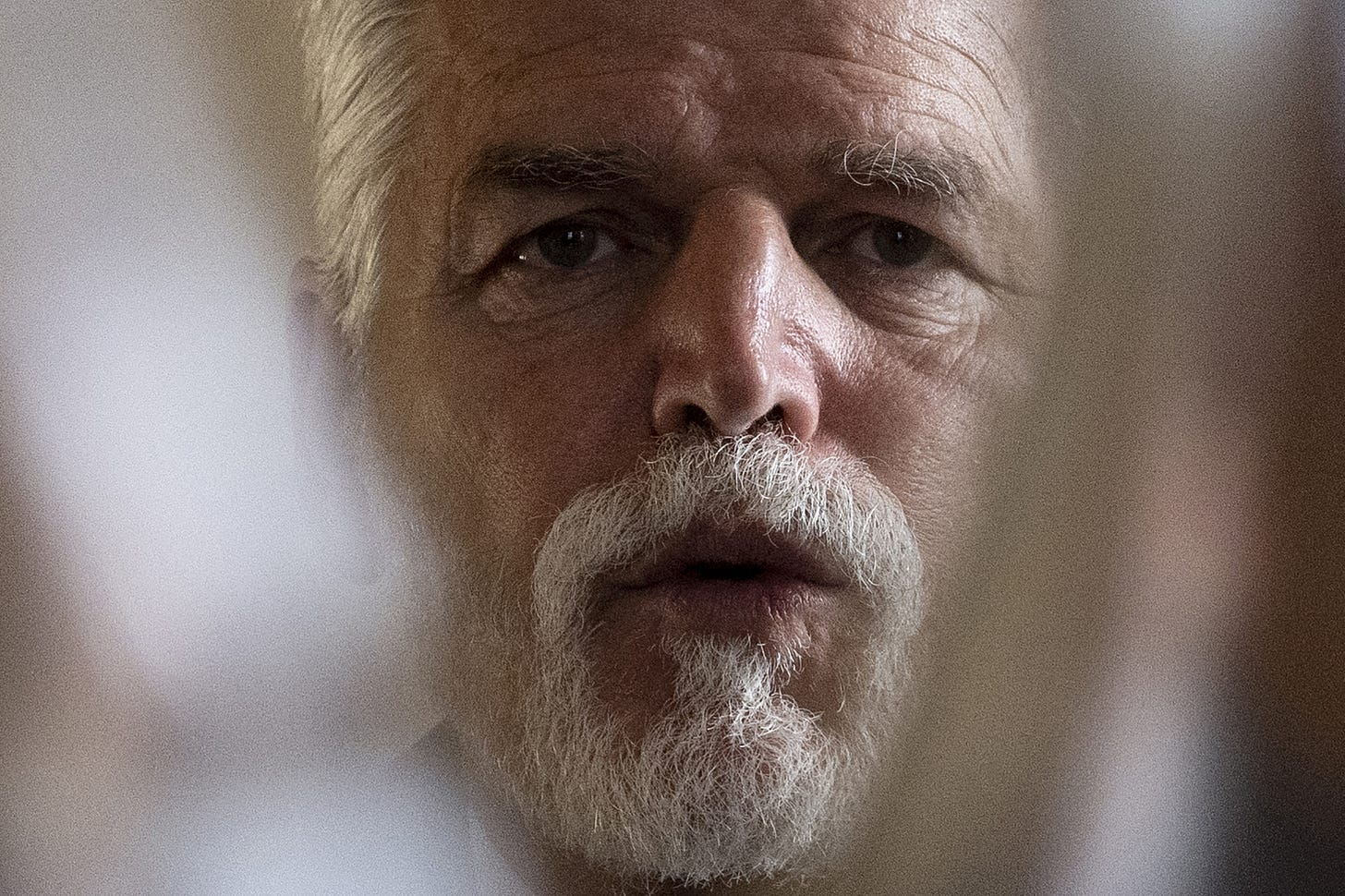

Petr Pavel’s first calls as president-elect included Ukraine’s Zelensky and Taiwan’s Tsai.

A Czech presidential election that ended last weekend with victory for former NATO general Petr Pavel was dominated by debate over the country's place in the West in a new era of war. The Czech Republic has been one of the world’s most generous nations in supporting Ukraine, but Russia's invasion has left its society bitterly divided between pro-Western forces, who want to see Vladimir Putin clearly defeated, and those who now want peace above all else.

In this context, President-elect Pavel's resounding victory is hugely significant for the West, even though Czech presidents don’t wield executive power. A former head of the NATO Military Committee and Czech Army chief, Pavel represents a school of thought that believes the only way to uphold liberal democracy at home is to bullishly support those fighting for it abroad.

Pavel has wasted no time in showing what this means in practice. His first calls as president-elect included talks with President Volodymyr Zelensky and Taiwanese President Tsai Ing-wen. European leaders and heads of state usually shy away from direct contact with the latter, for fear of stoking Beijing’s anger, but Pavel went one step further, expressing a wish to “meet President Tsai in person in the future.”

Beijing reacted furiously, describing Pavel's call as a "serious interference in China's internal affairs." But Chinese threats are increasingly impotent in Eastern Europe. In political circles, there is widespread dissatisfaction with years of empty economic promises from Beijing that have yielded poor results for the region’s growing economies.

The foreign affairs committee of the Czech parliament has recommended that the country leave China’s “14+1” scheme for economic partnership with Eastern European countries, echoing former member Lithuania’s complaints that the program brought “almost no benefits” and was a vehicle for promoting Chinese interests. And as public awareness of the cruelty of Xi Jinping’s regime grows, ties with Beijing now seem like an encumbrance without an upside—a stark contrast with Taiwan, which neatly combines democratic virtues with tangible economic benefits.

Czech Prime Minister Petr Fiala supported Pavel, saying “as a sovereign state, we decide whom we call and whom we meet.” Fiala insisted that the Czech Republic’s “One China” policy hasn't changed, although Pavel has suggested supplementing it with a “two system” principle for relations, arguing that “there is nothing wrong with having specific relations with Taiwan, which is the other system.” Following Pavel’s call, the speaker of the lower house of the Czech parliament announced her own plans to lead a delegation to Taiwan in March.

Yet while displaying admirable resolve, the Czech Republic must be careful not to throw away caution entirely. If Pavel follows through on his wish to become the first EU head of state to meet President Tsai, a diplomatic storm would ensue that could destabilize EU-China relations and, by extension, China’s relations with the West as a whole.

As the West faces down China's growing might and Russia’s revanchism, the main objection to Pavel among his opponents is that the former NATO general is just too hawkish. Given Pavel’s military background, it is understandable that some voters fear Pavel won't be inclined to strive for peace, and worry that a tendency of viewing global problems through a military lens could result in him exacerbating tensions rather than calming them.

Rival presidential candidate and former prime minister Andrej Babiš played on such fears during the campaign by promising not to “drag the Czech Republic into war.” He also latched onto a comment from Pavel that “permanent peace is an illusion,” taking the statement out of context to suggest the former general has zero interest in diplomacy.

Critics will view Pavel’s immediate contact with Taiwan after winning the presidency as a confirmation of their fears. The new president, they will think, is pointlessly goading the Chinese dragon, just as a top U.S. general warns that “Xi’s team, reason, and opportunity” are aligned for military action against Taiwan in 2025.

Yet despite such concerns—and despite polling suggesting that only a third of Czechs want their president to be overtly pro-Western—Pavel now has a powerful democratic mandate for his personal foreign policy agenda.

In an interview with the BBC released this week, Pavel has said Ukrainians “really deserve” to see their country join NATO “as soon as the war is over.” In another interview, he said he sees "no reason for limits" on conventional weapons deliveries to Ukraine, criticizing the "reserved attitude" of some countries towards supplying modern weapons. And during the election campaign, Pavel told me about his relief at the Czech government’s leading role in supporting Ukraine, with Prague among the most generous suppliers of military aid when measured against national resources.

When I asked about powerful pro-Russian elements of society that argue that Czechs share nothing with the U.S.-led global West, Pavel told me Czechs are “victims of a distorted education” when it comes to their own roots. Czechs are commonly perceived—by themselves and by others—purely as Slavs, but the country’s ethnic and cultural heritage is actually, he said, a blend of East and West. As he put it, “We are the contact point between those two worlds.”

Pavel’s conviction that, historically and culturally, Czechs do not fully belong to either the West or the East might help explain his belief that Western values must be vigorously defended at home and abroad. Liberal democracy is not the default state of affairs in this country, in his view; instead, it is a delicate construct with foundations that have still not fully set, and which must withstand constant threats from without and within. A similar attitude characterizes other hawkish Eastern European leaders, too, especially in Poland and the Baltic states.

When it comes to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and China's designs on Taiwan, it’s the smaller states of Eastern Europe that are pushing the boundaries on what democracies can—and should—do to combat the influence of tyrants and authoritarian regimes. With Pavel as head of state, the Czech Republic is set to become a bulwark of liberal democracy in the heart of Europe.