Taiwan and China Keep Eyes on Ukraine

They both want to see whether the United States will step up and lead.

Does what is happening in Ukraine matter much for Taiwan? It depends on whom you ask. I raised the question with several policy experts and government officials in Taiwan, and the results of those conversations are revealing.

“There’s no question that China is watching the crisis in Ukraine really closely,” says NBC News reporter Dan De Luce. “And if Russia succeeds in seizing Ukraine, Chinese leaders could see that as a green light to go after Taiwan.” Alternatively, Kharis Templeman, an expert on Taiwan at the Hoover Institution, argues that linking the fates of Ukraine and Taiwan is “lazy analysis.” The truth is likely somewhere in the middle. This should come as little surprise given that Taiwan’s government has set up a task force on the crisis in Eastern Europe. As Hsiao Bi-khim, Taiwan’s representative to the United States, told NBC News, “Like everyone else in the world, we are watching the situation with much concern and anxiety. . . . I think it’s pretty clear to all of us around the world that those undermining stability are China and Russia.”

But why is Taiwan watching so closely? It is not because Beijing will interpret a weak response to Russia as a green light for China to invade Taiwan. Nor is it simply a matter of assessing American credibility. But observers in Taiwan do seem to believe that the events in Europe, and the role America plays, will tell them, as well as observers in Beijing, something important about U.S. power, U.S. interests, global power distribution, and trends in the international system—all of which have implications for Taiwan.

The Sino-Russian axis—dangers and opportunities.

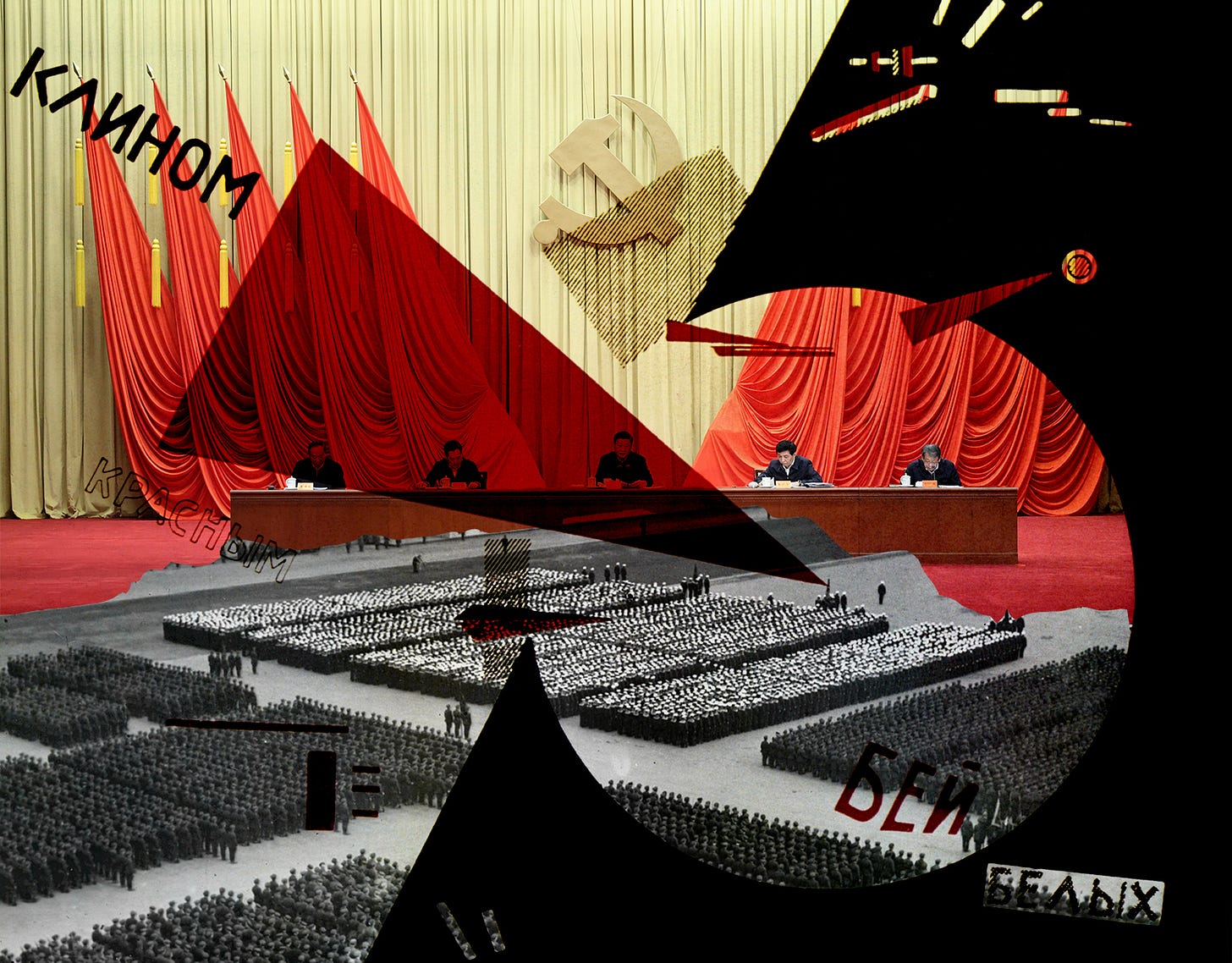

In December 2021, Xi Jinping told Vladimir Putin, as conveyed by the Russian president’s foreign policy adviser, “even though the bilateral relationship is not an alliance, in its closeness and effectiveness this relationship even exceeds that of an alliance.” Then, in a remarkable joint statement released on February 4, Putin and Xi put that sentiment to paper:

They reaffirm that the new inter-State relations between Russia and China are superior to political and military alliances of the Cold War era. Friendship between the two States has no limits, there are no “forbidden” areas of cooperation, strengthening of bilateral strategic cooperation is neither aimed against third countries nor affected by the changing international environment and circumstantial changes in third countries.

The statement indicates a newly intimate mutual embrace, so it raised alarm bells in Taipei. Although Russia’s acceptance of China’s One China principle is nothing new, Moscow’s public assertion in such a high-profile document that “Taiwan is an inalienable part of China” and that Russia “opposes any forms of independence of Taiwan”—likely made in exchange for Beijing’s public opposition to NATO enlargement—raised eyebrows. Concerns that Russia could provide assistance to China during a Taiwan Strait war seemed far more realistic than they had in the recent past. The non-alliance could greatly complicate not just American efforts to intervene in such a conflict, but also those of Japan and other potentially interested parties.

But some in Taiwan also see an opportunity in this trans-Eurasian snuggle. Xi Jinping has personally invested in his relationship with Putin, having met with him on 38 occasions. If the bromance turns sour or if the consequences of Russian actions redound to China, that could damage Xi at home. There is thus an opportunity, as one scholar put it to me, to weaken Xi by weakening Putin.

A robust and effective U.S.-led response to the invasion of Ukraine could instill greater caution in Xi, who must already be wondering if the democratic world would punish China for using force against Taiwan in the way it has thus far punished Russia. Moreover, if Xi’s embrace of Putin comes to be seen internally as a misstep, the Chinese leader might opt for a more restrained approach to international affairs as he heads into this fall’s 20th Party Congress, in which he aims to secure a third term as Communist Party general-secretary.

Does democracy matter?

The Russia-China joint statement devotes six full paragraphs to the topic of democracy. The two authoritarian states claim that they are, in fact, democracies and argue that “the advocacy of democracy and human rights must not be used to put pressure on other countries.” Clearly, Moscow and Beijing believe there is an ideological component to their competition with U.S.-led coalitions. It remains an open question just how important that ideological component is to American leaders.

Even as many Americans in the policymaking world agree that Taiwan matters to U.S. interests, they may not agree on why it matters. In general, however, analysts and policymakers subscribe to one or more of three basic rationales for Taiwan’s importance: a strategic import imbued by its geography; its economic relationship with the United States and the central node it occupies in global technology supply chains; and its democracy.

President Joe Biden has described competition between democracy and authoritarianism as a defining feature of our time. In a speech on February 16, he made clear that he sees what is happening in and around Ukraine as proof positive of that outlook. “If we do not stand for freedom where it is at risk today,” he asserted, “we’ll surely pay a steeper price tomorrow.” It’s a message that must appeal to President Tsai Ing-wen, who has described Taiwan as “sitting on the frontlines of the global contest between the liberal democratic order and the authoritarian alternative.” But will what transpires in Eastern Europe reveal that supposed Biden worldview as little more than rhetoric?

There are concerns in Taiwan that if the United States fails to ensure Ukraine’s survival as an independent, democratic state, the third rationale for defending Taiwan will be proven unpersuasive for the current crop of decision-makers in Washington. To be clear, no one I spoke to in recent weeks has suggested that the United States should go to war with Russia to reassure Taiwan. But Americans should be aware that, in political warfare efforts aimed at Taiwan, China will make hay of America’s inability to save a fellow democracy, and that certain elements of the pan-Blue camp in Taiwan will adopt a similar narrative in their domestic politicking. There are potentially significant implications for U.S.-Taiwan relations.

Collective security—what is it good for?

In a recent interview with the Huffington Post Italy (in English here), J. Michael Cole, a research fellow at the Prospect Foundation in Taipei and a longtime Taiwan resident, noted the differing security architectures in Europe and Asia. Unlike Asia, Europe has a large collective security arrangement in the form of NATO. “Initiating a concerted response to Chinese aggression against Taiwan,” he argues, “would be more difficult than among EU and NATO members, even if there, too, unity is often elusive.” Put another way, if NATO cannot mount an effective response to the crisis centered on Ukraine—which is, after all, right next door—what hope is there for the United States to mobilize its far more disparate group of allies in Asia to respond to a crisis in the Taiwan Strait?

What has become apparent is that at least some in Taiwan see in Europe right now an opportunity for the United States to prove what collective defense can accomplish. And while the security of NATO members is not, in a narrow sense, directly threatened, Europe’s peaceful order—in which European countries have thrived and which NATO has played a central role in maintaining—may be crumbling. It is little wonder that some in Taiwan see parallels to Taiwan’s circumstances; Taiwan, after all, has no formal allies of its own.

But beyond those parallels, if the United States is to be successful in establishing an “anti-hegemonic coalition”—to use Elbridge Colby’s preferred terminology—in Asia, it behooves the United States to prove it can successfully lead an extant one in Europe against a foe less powerful than China. Right now, with the advent of major war on its doorstep, that coalition in Europe appears to be failing.

Colby, moreover, recognizes that an anti-hegemonic coalition centered on America’s hub-and-spokes alliance model in Asia may not be sufficient. He argues for pursuing collective defense arrangements, contending in The Strategy of Denial that “the more cohesive the United States can make its alliances in resisting China’s bid for regional hegemony, the better.” But if NATO, the sine qua non of collective security, cannot defend the peace in Europe and prevent growing threats from emerging on its doorstep, what hope is there for Asian states to get past their allergy to collective security?

European security dynamics: Will free Europe continue its embrace of free Taiwan?

Taiwan has been enjoying a European moment. It has exchanged representative offices with Lithuania. Slovenia and Taiwan are likewise opening trade offices in each other’s capitals, and the Czech Republic and Taiwan have drawn closer in recent years despite Chinese opprobrium. These developments have potentially beneficial long-term consequences for stability in the Taiwan Strait. A diversity of economic partners weakens China’s economic leverage vis-à-vis Taiwan, while a diversity of diplomatic partners complicates China’s decision-making regarding aggressive action against Taiwan.

Even when European states are not explicitly focused on Taiwan, they have increasingly cast their eyes toward China with newfound skepticism. In its Brussels Summit Communiqué last June, NATO raised concerns about the People’s Republic:

China’s stated ambitions and assertive behavior present systemic challenges to the rules-based international order and to areas relevant to Alliance security.

The United Kingdom embraced an “Indo-Pacific tilt” in the course of its 2021 “integrated review of security, defense, development, and foreign policy.” Last October, the European Parliament adopted a resolution urging the EU to “intensify EU-Taiwan political relations” and to “consider Taiwan a key partner and democratic ally in the Indo-Pacific . . . that could contribute to maintaining a rules-based order in the middle of an intensifying great power rivalry.” France’s new Indo-Pacific strategy points to China’s growing power, noting that “its territorial claims are expressed with greater and greater strength” and that tensions are rising “at the Chinese-Indian border, in the Taiwan Strait and on the Korean peninsula.”

Now, observers in Taiwan wonder whether this recent attention can be sustained. The invasion in Ukraine could mark a fundamental shift in security dynamics on the European continent. To an extent not seen in decades, European countries will be consumed with far narrower security concerns. All eyes will be on Russia, with much less attention to spare for the far end of the Eurasian landmass. That may be good for NATO security, especially if this is the crisis that finally spurs members to substantially increase their defense spending, as Chancellor Olaf Scholz just announced Germany would do. But a Europe that turns inward is a troubling development for those observers in Taiwan that see diversified foreign interest in cross-Strait affairs as a stabilizing factor in regional security.

An inward turn in Europe could, in theory, free Washington to focus on the Indo-Pacific. If Europeans are better able to ensure security in Europe, the United States might be able to rebalance its military forces and strategic attention to the China challenge. But that is likely wishful thinking: Even if Asia was the decisive theater for defending American security interests before Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, it no longer is—at least not in the short term. Putin’s Russia has embraced bald-faced aggression in a way Xi Jinping’s China has not (yet). Putin’s Russia has openly brandished nuclear weapons to achieve its objectives—a step which Xi’s China has thus far eschewed. Washington will find it needs to keep one eye firmly fixed on Europe even as European allies bear more of the burden for their own defense.

Perhaps most surprising, my interlocutors in Taiwan do not seem to be fretting about this outcome. There is at least some recognition of Europe’s importance not only to American security interests, but to Asian security as well. Deterrence in Asia, it seems, is not simply a matter of the military balance. When it comes to Beijing’s decision-making about Taiwan, there are various factors at play.

The balance of military power: Who needs it?

Writing in the Wall Street Journal last month before the Ukraine invasion, Oriana Skylar Mastro and Elbridge Colby argued against additional deployments of U.S. forces to Europe to shore up NATO. “Sending more resources to Europe is the definition of getting distracted,” they write. “The U.S. should remain committed to NATO’s defense but husband its critical resources for the primary fight in Asia, and Taiwan in particular.” While some Taiwanese that I spoke to agreed with Mastro and Colby’s contention that Taiwan is more important to American interests than Ukraine, I did not find agreement with the insistence that Ukraine is a distraction. And while there are concerns about resource distribution, it is not at all clear that husbanding resources for Asia will provide the deterrent boost that Mastro and Colby claim.

Rather, Xi Jinping might interpret the husbanding of resources as proof positive that American power is in terminal decline. The effect, one argument goes, may be to further convince Xi Jinping that his assessment of a rising East and declining West is correct. If America the Decadent is unable to exercise global leadership in the way it has since World War II; if it is offloading responsibilities to others; if it must conserve resources for a future fight—well, that is an America that China can defeat in battle, Xi might think, even if the arithmetic says the United States is ready for such a fight. And, of course, who is to say that in the event of a conflict over Taiwan, Washington would not again decide to “husband its critical resources” for a time when national interests, even more narrowly defined, are at stake?

To be sure, the military balance in Asia matters greatly. But it is not all that matters. Adversary perceptions of American national power, national will, and national character all factor into decisions about the use of force. Right now and in the weeks and months to come, my conversations suggest, it is America’s approach to Europe, not Asia, that will primarily shape those perceptions in China.

Will America lead?

There is clearly a diversity of opinion in Taiwan on these questions. Even so, the views and arguments shared here reflect the thinking of influential national security elites and elements of the Tsai administration, who see their country’s fate tied, in important ways, to Ukraine’s, though not for the reasons many American commentators have asserted. There are certainly concerns that a diversion of U.S. attention to Europe in the coming months might provide China with an opportunity to more aggressively squeeze Taiwan via coercive displays of military might, disinformation campaigns, employment of economic leverage, and other so-called “gray zone” tactics. But the greater concerns, at least among those with whom I spoke, are that the United States will fail to lead an effective response to the Russian invasion and that Putin will ultimately succeed in his endeavor. That outcome would mark a world made new—a world far less conducive to Taiwan’s survival as a thriving, independent, democratic state.