The Abortion Pill, the FDA, and Supreme Court

What will happen to Judge Matthew Kacsmaryk’s ruling effectively banning the sale of the drug?

On Friday, Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito, in a one-paragraph order, “administratively stayed” an April 7 ruling by a federal district court judge in Amarillo, Texas, suspending the Food and Drug Administration’s twenty-three-year-old approval of mifepristone, a drug used as part of a two-part regimen to end early-stage pregnancies. Alito’s ruling came at the request of the U.S. solicitor general, as well as Danco Laboratories, a New York pharmaceutical company that distributes mifepristone. Alito’s order maintains the status quo—that is, access to the drug across the nation—until 11:59 p.m. tonight.

The stakes are high. Over half of all abortions in 2020 were medically induced, and since last year’s decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, thirteen states have enacted or reinstated complete abortion bans—even in cases of rape, incest, or life-threatening conditions for the mother. An analysis by the Association of American Medical Colleges found that new doctors applying for residency programs are avoiding those states, as well as several others that have enacted early-gestation abortion bans. Not only do women residing in those states lack abortion access, therefore, but Dobbs is also now exacerbating existing problems with health care, particularly for low-income women and their children.

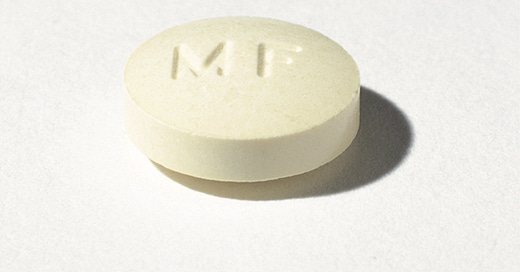

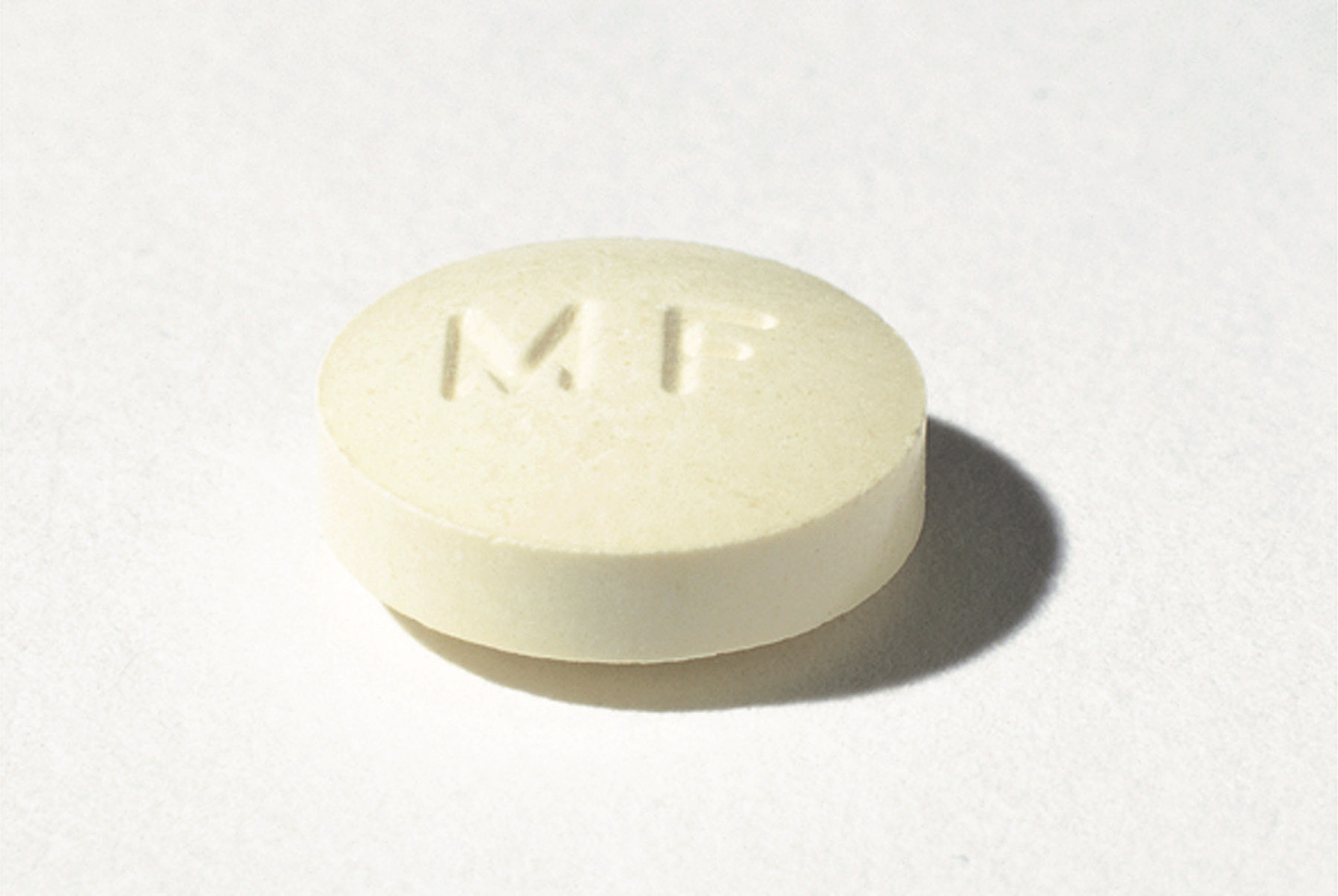

Now comes the mess involving mifepristone, which the FDA approved in 2000 and for which the agency began permitting access by mail in 2021. Setting aside the substance of what it would mean if mifepristone, prescribed each year to hundreds of thousands of Americans, were no longer accessible, the case raises disturbing questions as a matter of law.

Judge Matthew Kacsmaryk, the Trump appointee responsible for the decision, is clearly out of control on a range of issues that he has no business legislating from Amarillo. But short of impeachment, federal judges serve for life. The answer to his excesses is to appeal his rulings to higher courts. In this case, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit reversed his suspension of FDA approval for mifepristone, except for mailed prescriptions, which it was willing to halt. Alito suspended Kacsmaryk’s entire decision. For now.

The stakes are also high because the legal basis for Kacsmaryk’s decision has nothing to do with the underlying rationale in Dobbs. That case held that there is no constitutional right to abortion; Kacsmaryk’s 67-page ruling strikes at the heart of the FDA’s power to regulate drugs. Over 100 scientific studies covering over 124,000 pregnancy terminations across 26 countries over 30 years have confirmed the safety and effectiveness of mifepristone. Over 99 percent of those who took the medication experienced no serious side effects.

Which is why Kacsmaryk’s decision is so troubling. After whisking over threshold issues of the plaintiffs’ standing to bring the lawsuit and other procedural flaws, he turns to the bread-and-butter standards for judicial review of regulatory actions by federal agencies. Under a 1946 statute called the Administrative Procedure Act, Congress authorized federal courts to hear lawsuits challenging rules made by agencies under a standard known as “arbitrary and capricious review.” The test is deferential, the rationale being that agencies like the FDA have specialized expertise that federal judges, who are generalists, do not possess. Agency rulemaking typically takes a couple of years, and it involves a comment period in which regular citizens—as well as other experts and industry groups—can weigh in on a proposed rule to make it better. Then it goes through numerous other statutory wickets aimed at a range of policy objectives, such as minimizing impacts on small businesses and even preventing unnecessary and burdensome data collection. The process is laborious and painstaking—which is a good thing, because for agencies like the FDA, personal health and safety hangs in the balance.

What’s more, in most cases the question before the court is whether a regulation is consistent with the statute giving the agency the power to issue the regulation in the first place. But in this case, the question wasn’t compliance with a statute—instead, Kacsmaryk was tasked with determining whether the FDA complied with its own regulations, a question that under Supreme Court case law should also trigger judicial deference to the agency. Here, FDA regulations require that drugs such as mifepristone be “studied for . . . safety and effectiveness in treating serious or life-threatening illnesses.” They must also “provide [a] meaningful therapeutic benefit to patients over existing treatments.”

Kacsmaryk ruled that the agency’s approval of the drug back in 2000 was “arbitrary and capricious” in part because pregnancy is not an illness. He admits that “complications can arise during pregnancy, and said complications can be serious or life-threatening.” But for Kacsmaryk, the key flaw in the FDA’s longstanding drug approval decision was its failure to treat pregnancy as a “natural process essential to perpetuating human life.” Even though chemical abortions avoid surgical ones, he added, they somehow provide no “meaningful therapeutic benefit to patients,” so the FDA’s approval of mifepristone violates the FDA’s own drug approval regulations for that additional reason.

Keep in mind, again, that Kacsmaryk’s legal authority here was limited. The FDA is supposed to get deference as a matter of law. The reason for that deference, again, is that Congress tasks certain agencies with making certain regulatory and policy decisions because of their specialized expertise.

Kacsmaryk’s abject power-grab in one of the nation’s most divisive culture wars is an insult to the rule of law and the legitimacy of the judicial branch of the federal government. This much should starkly be evident to at least five members of the right-leaning Court. The FDA regulates over 78 percent of the U.S. food supply and more than 20,000 marketed drugs, putting over 2.7 trillion dollars in the consumption of food, medical products, and tobacco within the FDA’s jurisdiction. Although there are valid arguments for urging Congress to take back its legislative power from executive branch agencies and do the dirty work itself, there is no conceivable logical basis for handing that power off to federal judges.

The justices will have to decide whether to extend Alito’s decision to stay Kacsmaryk’s maneuver until the Supreme Court can thoroughly consider the issue, or instead do what it did pre-Dobbs by enabling Texas’s six-week abortion ban to take effect while it considered what to do with Roe v. Wade. Let’s hope Alito’s decision is a sign of a shift in the Supreme Court’s judiciousness.