The Arrest of Julian Assange Is Not Bad for Journalism

Assange isn't being charged because he published state secrets.

For seven years, Julian Assange, the founder of Wikileaks, had been holed up in the Ecuadorian embassy, initially to avoid extradition to Sweden, where he had faced rape charges that were subsequently dropped, but also to avoid extradition to the United States.

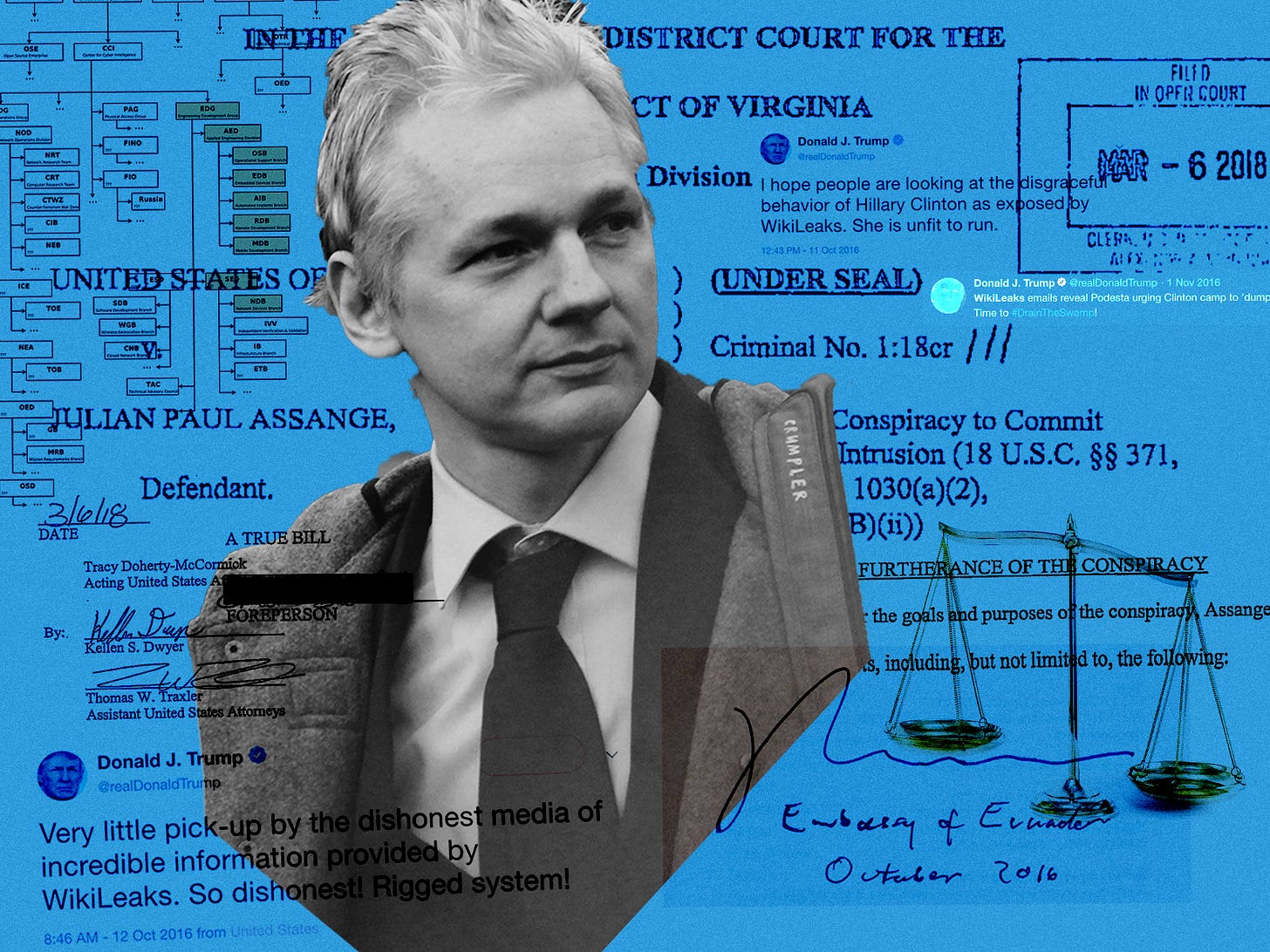

Reports had circulated for years that a grand jury in the Eastern District of Virginia had been hearing evidence against Assange, but whether or not he was actually wanted in America had been unclear until this past November, when, to the embarrassment of the Justice Department, a court filing inadvertently revealed that a sealed indictment had been filed. Now that Ecuador has evicted Assange from its embassy and he has fallen into the hands of the British police and faces extradition to the United States, the Justice Department has published the sealed indictment.

We have arrived at an interesting juncture.

Edward Snowden, the mega-leaker who has taken refuge in Vladimir Putin’s Russia after blowing some of America’s closely held counterterrorism secrets, has voiced outrage about Assange’s arrest, tweeting:

Given that journalists in Russia are regularly murdered by Vladimir Putin’s thugs, and that Snowden, blending motives of self-preservation and hypocrisy, has been very quiet about that subject, his expression of concern about a “dark moment” for press freedom is comical.

Be that as it may, the indictment of Assange does raise questions about the extent of First Amendment protections for journalists. Assange is charged with having engaged in a conspiracy with former U.S. Army intelligence analyst Chelsea Manning in connection with the 2010 publication on WikiLeaks of a huge trove of classified documents pertaining to the war in Iraq and other sensitive subjects.

It’s important to understand the precise nature of the crime.

Mainstream journalists covering national security obtain and publish classified information every day of the week. Such material is the bread and butter of journalism and the public benefits enormously from what is a semi-tolerated and, in some instances, officially sanctioned—and sometimes encouraged—practice. Mainstream journalists also do more than merely obtain classified information: They actively solicit it. In other words, as part of their normal practice, they encourage government officials who have sworn to protect government secrets to break the law. Among other things, major newspapers and television networks maintain encrypted electronic drop-boxes to which government officials can covertly and/or anonymously send classified information with some—though not absolute—protection.

Paradoxically, it was the liberal Obama administration which launched the fiercest crackdown on leakers in American history. It prosecuted more such cases than all previous administrations combined and used remarkably aggressive techniques—including the use of search warrants and subpoena powers to obtain the internal communications of news organizations.

But the most significant fact is that in all of modern American history, no journalist has ever been prosecuted for obtaining or publishing classified information.

On a number of occasions, the federal government has threatened to launch such prosecutions, but it has never followed through.

In an indictment filed by the Obama Justice Department, James Rosen of Fox News was named as an unindicted co-conspirator of State Department leaker Stephen Jin-Woo Kim. Kim was convicted under the espionage statutes and sentenced to prison. But Rosen was never prosecuted, undoubtedly because Eric Holder’s Justice Department did not want to test the limits of the First Amendment.

The big question posed by the indictment of Assange is whether, under the Trump administration, such restraint has now come to an end. And this poses a subsidiary question: Is Julian Assange a journalist?

Of course, “journalist” is not an official status. One of the great things about our country is that anyone can be a journalist at any time. Journalists are fond of saying that theirs is the only industry mentioned in the Constitution. It is true that, along with guaranteeing freedom of speech, the First Amendment also guarantees freedom of the press. But that is not because the framers of the Constitution were seeking to bestow a special privilege on an industry called “the press.” Rather, they sought to make it clear that they were protecting both oral and written expression. As Byron White made it clear in the Branzburg decision, that written protection extends to all Americans not just a special class of newsmen: "It is the right of the lonely pamphleteer who uses carbon paper or a mimeograph just as much as of the large metropolitan publisher who utilizes the latest photo composition methods."

The First Amendment also, amazingly enough, protects foreigners—even hostile foreigners—and it does so for a readily understandable reason. As one federal judge put it in a case involving a prohibition on importing certain foreign magazines, the "essence" of the First Amendment right to freedom of the press "is not so much the right to print as it is the right to read" (emphasis added). So the question of whether Julian Assange is or is not a journalist is irrelevant. As someone who specializes in the publication of classified material on the Wikileaks website, he enjoys as much First Amendment protection as the next guy.

If Assange were to be successfully prosecuted merely for publishing U.S. government secrets that would indeed be a “dark moment” for press freedom, as Snowden put it.

So a great deal hinges not on the publication of U.S. government secrets but how those secrets were obtained.

And here the issues become gray.

When James Rosen was named as an unindicted co-conspirator, he was communicating with Kim using aliases and a coded communication system. Their system was not particularly sophisticated. According to Justice Department documents in the case, a single asterisk in an email was supposed to indicate that "previously suggested plans for communication [were] to proceed as agreed," while emails containing two asterisks "mean[t] the opposite." Rosen also actively solicited classified information from Kim, tasking him with obtaining and conveying "internal State Department analyses" and "what intelligence is picking up" about North Korea.

Both the covert communication system and the solicitation, especially combined, seem like problematic journalistic practices. Counterintelligence authorities viewing such activity would not be out of line if they took it for espionage. Certainly, espionage was not what James Rosen was up to. But if a journalist from, say, Communist China’s main publication, the People’s Daily, did such a thing, the FBI would have every right to pounce.

As the unsealed indictment of Assange reveals, Assange like Rosen, solicited highly classified material from Manning. And like Rosen, he came into the unauthorized possession of such material. Both are crimes, but not crimes for which journalists have ever been charged.

But Assange went a great leap further than Rosen, however: He entered into an agreement with Manning to help crack a password on a government computer to expand access to government secrets.

As a journalistic practice, this is a complete novelty. Legitimate journalists engage in a number of activities to obtain newsworthy government secrets that might or might not enjoy First Amendment protection; our courts have never had occasion to draw a line and, fortunately, the Trump administration—despite the president’s ranting against the media, and his extraordinary charge that the media are "the enemy of the people”—has not deployed the legal instruments at its disposal that would force such line-drawing. That remains a dangerous possibility because there are vague statutes on the books, which, depending on how the Supreme Court interpreted them, could criminalize a lot of what has come to be ordinary—but is extraordinarily valuable—journalism.

The indictment of Assange will bring this era of judicial silence to an end, but, fortunately, is unlikely to set a precedent that in any way endangers legitimate newsgathering. The Justice Department seems to have tailored the indictment in way that will do minimal collateral damage. Assange faces a single charge of conspiracy to commit computer intrusion. The “overt acts” that comprise the crime involve various phases of hacking. Almost all journalists and defenders of the free press agree that hacking into government computers to obtain secrets—a form of breaking and entering to commit outright theft—is not a form of newsgathering that should enjoy First Amendment protection.