The Claremont Institute’s Bogus Censorship Charge

Its senior fellow John Eastman helped engineer Donald Trump’s plans for electoral chaos on Jan. 6. Now the think tank claims it’s being canceled.

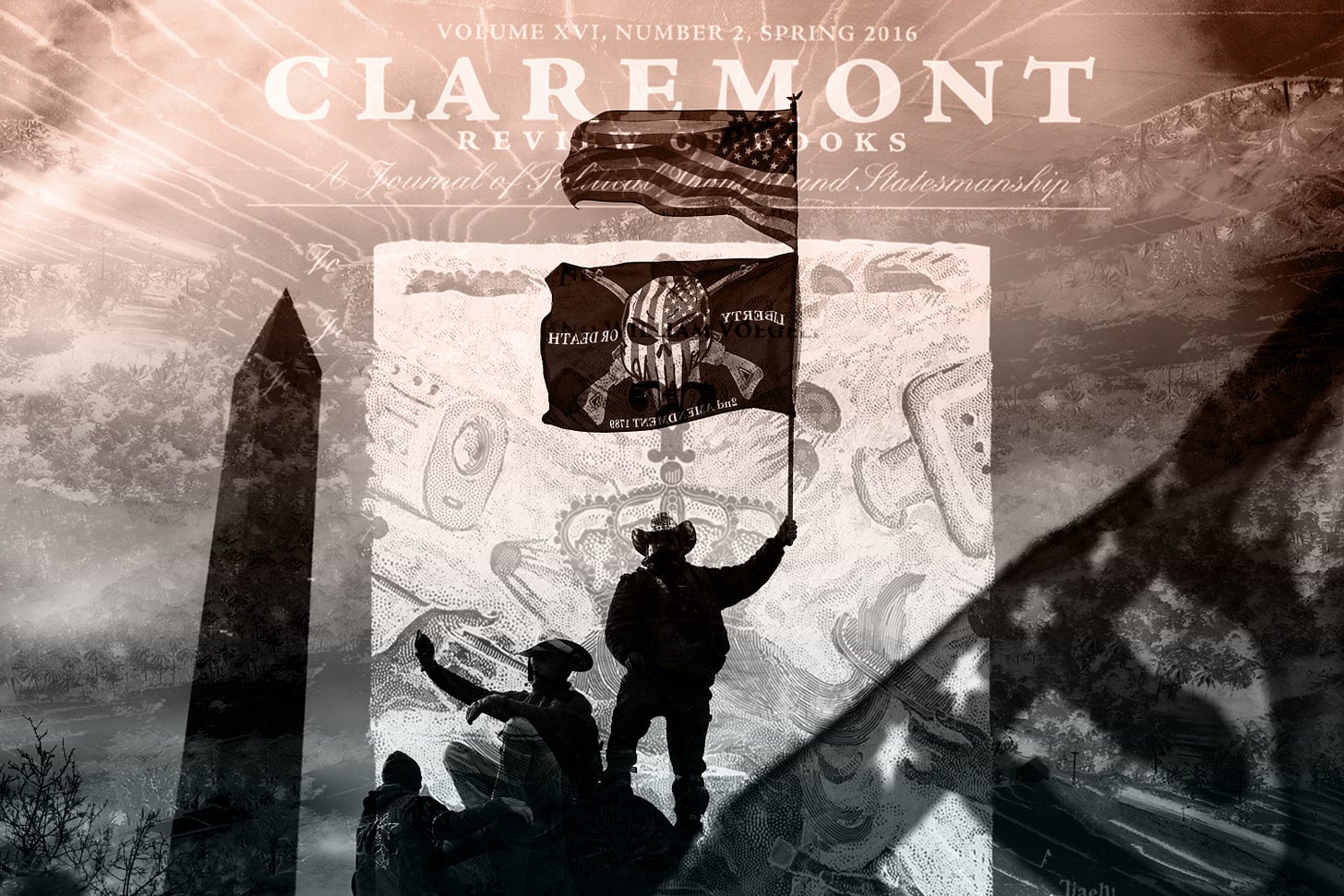

You may know the Claremont Institute as the intellectual home of John Eastman, the lawyer behind the infamous six-point memo, who helped President Donald Trump concoct his plan for rejecting the Electoral College results on January 6. Or you may know the Claremont Institute as the publisher of the gross “Flight 93” essay comparing the 2016 election to a terrorist hijacking and warning Americans to “charge the cockpit” (i.e., vote for Trump) “or you die” (i.e., see the country wrecked under a Democratic president).

In recent weeks, the institute has been entangled in a dispute with the American Political Science Association. APSA is the country’s premier professional association for political scientists, and the dispute with Claremont concerned Eastman’s participation in APSA’s annual conference.

Spoiler alert: The conference is over, Eastman did not participate, and Claremont is claiming it has been censored—and even affirmatively defending Eastman and naming him in its latest fundraising efforts. In a sense, this is just a minor kerfuffle, but the stakes are higher than they might at first appear. It is worth taking some time to unpack the factual record and sort out the disputed claims.

Do American political scientists have a legitimate beef against John Eastman, and even against the Claremont Institute?

Are Claremont and its senior fellow John Eastman the victims of a “combined disinformation, de-platforming, and ostracism campaign,” the goal of which is to “prevent the Claremont Institute or its scholars from presenting our views,” as the institute’s leaders have proclaimed?

Is Patrick Deneen right when he suggests that this was “a political purge” that prefigures the end of serious thought and inquiry in American academia—the final closure of the American mind?

The conflict between APSA and Claremont doubtless seems mostly inconsequential from the outside. But it manifests, in microcosm, vital civic questions. Questions like: How much radical thought—and radical or unlawful action—can or should be accommodated by civil society in a liberal democracy? What obligations do American intellectuals and scholars owe to the American system of government? The episode—and the response to it on the part of Claremont’s leadership and the institute’s apologists—also brings into relief the question of whether there is any hope for a saner future for American conservatism.

Let’s dig in.

I. John Eastman’s Plan for Jan. 6

As with almost any instance of so-called cancel culture, the question at hand is ultimately a specific substantive one: What did John Eastman do and was it wrong?

While many details regarding what John Eastman was up to around January 6 have yet to emerge, the general outline has now been widely reported. Let’s briefly rehearse what we know.

On December 9, 2020, Eastman filed a motion and brief on Donald Trump’s behalf in a lawsuit that the attorney general of Texas brought before the U.S. Supreme Court. The suit sought to invalidate the elections in several swing states that went for Joe Biden. The Court quickly tossed the suit, but Eastman’s brief is still noteworthy for making the two broad claims that would underlie his subsequent schemes: that Democratic officials in the swing states had illegally or unconstitutionally changed state election laws, and that these changes likely induced fraud. He also strongly insinuated that Trump couldn’t have lost the election, given the particular combination of counties and states that he did win. “A large percentage of the American people know that something is deeply amiss,” Eastman wrote. Some of his assertions had already been rebutted weeks earlier. Yet Eastman would continue to make florid claims of fraud all the way through January 6, when he told the audience at Trump’s White House rally—without evidence—that “a secret folder in the [voting] machines” was used to cast fraudulent votes for Biden.

On December 24, 2020, Eastman was reportedly asked by a Trump aide to provide Trump with a memo about the process by which Congress certifies electoral results each January 6 after a presidential election. He did so. Two distinct versions of the memo have become public: A long version that involved “War Gaming the Alternatives,” and a short version, which Eastman has called “a preliminary, incomplete draft,” that takes one particular alternative and provides a more particularized plan.

Eastman’s long memo begins with an articulation of the premises of the entire gambit: Part I of the memo is called “Illegal conduct by election officials” and provides a summary view of alleged voter fraud and illegal Democratic interference in the election laws in the lead-up to the election. (As Eastman now puts it: “The memo’s premise was that state election officials ignored election laws, such as signature verification requirements, prohibitions on ballot harvesting, and allowance of observers during ballot counting.”)

This argument leans heavily on the idea that Democratic officials (and as far as Eastman and Trump cared, only Democratic officials) seized upon the conditions of the COVID-19 pandemic to unlawfully and in some cases unconstitutionally change election processes. The many lawsuits alleging such abuses (including in each of the states cited by Eastman) were unsuccessful. By the time Eastman wrote his memo, most of these legal proceedings had already concluded. Several of the lawsuits were rejected for procedural reasons rather than substantive reasons, and there are some key legal questions that the courts chose not to address. But for all practical purposes, the premises of the Eastman memo have been rejected.

Eastman’s long memo goes on to claim that seven states—Georgia, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, Michigan, Arizona, Nevada, and New Mexico—submitted to Congress two different slates of electoral results: “The Trump electors” in the seven states “cast their electoral votes, and transmitted those votes to the President of the Senate (Vice President Pence). There are thus dual slates of electors from 7 states.” The short memo contains the same claim: “7 states have transmitted dual slates of electors to the President of the Senate.”

The claim that there were “dual slates” of electors—the predicate for Pence’s taking matters into his own hands on January 6—is extraordinarily dishonest. Here is what happened:

On December 14, 2020, electors from all fifty states and the District of Columbia gathered to “meet and give their votes,” as required by federal law. Signed certificates indicating how the electors voted were, again as required by federal law, transmitted to various government officials, including Vice President Mike Pence, in his capacity as president of the U.S. Senate. Biden received 306 votes; Trump received 232.

That same day, in the states Eastman mentions—all of which Trump lost in the popular vote—the Republicans who would have been Trump electors if he had won the popular vote got together in mock ceremonies to “cast” their electoral votes for Trump. In one case (New Mexico), this was in a state Trump lost by double digits. Contemporaneous press reports are light on details, so it is not entirely clear that each of the participating Republicans in each of these seven states were the original Trump electors.

The actions of these Republican gatherings had no more legitimacy than if a group of strangers met in a bar and claimed to be a state’s electors. Indeed, in Arizona, something like that happened: In addition to the “official” defeated Republican electors posing as casting votes for Trump, a second group of random Republicans play-acted at casting votes for Trump, too.

In every one of the seven states Eastman’s memos mentioned, state officials transmitted to Congress the required certification of Biden’s electors. Not a single state official took the Republican alternative slates of electors seriously enough to transmit them formally to Congress.

In writing his memo, Eastman may have been drawing on the ideas of Jeffrey Clark, a high-ranking appointee in Trump’s Department of Justice (DOJ). In late December, Clark urged the acting attorney general, Jeffrey A. Rosen, to (1) tell officials in several states that DOJ has “identified significant concerns” in their states’ elections; and (2) recommend the legislatures of those states consider giving their imprimatur to the illegitimate Republican slates of electors or appointing an entirely new set of electors—thereby overthrowing those states’ duly certified votes.

In a recent article discussing his memos, Eastman concedes that the Republican electors who gathered in these states on December 14 did so “of their own accord.” He draws a comparison to the actions of Democratic electors in the unusual circumstances in Hawaii in 1960, conveniently ignoring the many ways in which that case was unlike the circumstances of 2020.

Part I of Eastman’s long memo, then, is thick with distortions.

Having asserted the existence and legitimacy of alternate slates of electors, Eastman’s next move, in Part II of the long memo, is to argue that the vice president, in his capacity as president of the Senate, has the authority to resolve disputes over conflicting slates of electors. (“There is very solid legal authority, and historical precedent, for the view that the President of the Senate does the counting, including the resolution of disputed electoral votes,” Eastman writes. “The fact is that the Constitution assigns this power to the Vice President as the ultimate arbiter. We should take all of our actions with that in mind.”)

The assertion that the vice president has this power has been widely discussed and rejected. One could argue that back in 2000, John Eastman himself rejected the assertion he embraced in 2021. The most powerful rejection, of course, came from Vice President Mike Pence in his January 6 letter explaining that he could not constitutionally claim authority in the way Eastman prescribed because to do so would violate the design of the Constitution (“Vesting the Vice President with unilateral authority to decide presidential contests would be entirely antithetical to that design”). Pence’s letter quotes as an authority the federal judge J. Michael Luttig—the judge for whom Eastman clerked.

In Part III of the long memo, Eastman turns to gaming out various paths through January 6. The permutations here depend on two variables: whether or not Vice President Pence goes along with Eastman’s assertion that there are alternative slates of electors, and whether or not Vice President Pence accepts and acts on Eastman’s claim that he wields the authority to settle such a dispute. If Pence does neither, the victory is Biden’s. But if Pence is willing to take matters into his own hands, then Trump has a chance. The long memo concludes with a plea:

I have outlined the likely results of each of the above scenarios, but I should also point out that we are facing a constitutional crisis much bigger than the winner of this particular election. If the illegality and fraud that demonstrably occurred here is allowed to stand—and the Supreme Court has signaled unmistakably that it will not do anything about it—then the sovereign people no longer control the direction of their government, and we will have ceased to be a self-governing people. The stakes could not be higher.

The implication is clear: If Pence doesn’t listen to Eastman and act, the country is lost. It is Pence’s turn to charge the cockpit.

In the short memo, Eastman charts a specific path through the alternatives that he presented in the longer one. This is where we find the six-point plan of instruction. Step 2 of the plan requires the vice president to announce that he has “multiple slates of electors'' for Arizona. Step 3 of the plan presumes that Pence will make the same false claims about “ongoing disputes” in six other states. It concludes: “Pence then gavels President Trump as re-elected.” From here, Eastman anticipates resistance (“howls”) from the Democrats. He advises Pence to send the matter to the House of Representatives (“So Pence says, fine”), where he expects Republicans to give the win to Trump.

On January 4, Eastman met with Trump and Pence in the Oval Office. He says, and others have reported, that in that meeting he equivocated both about Pence’s constitutional authority and about the status of the slates of electors. He claims he told Pence it would be “foolish” to reject the duly certified Biden electoral votes if the relevant state legislatures hadn’t first endorsed an alternate slate.

That may be true, but it contradicts the entire thrust of his memos (and so then is a tacit admission of their dishonesty). Besides, whatever reservations Eastman says he had did not stop him from standing on a dais in front of Trump’s crowd on January 6, crying fraud, and insisting that Pence had no choice but to act.

A person doesn’t need a law degree or a Ph.D in political science to see that John Eastman’s memos didn’t amount to ordinary, professional legal counsel.

Both his memos take as a premise widespread fraud and illegality in the 2020 election. Almost all such claims had by that point failed in court, and claims of widespread voter fraud had no merit.

Both memos also take as a premise the existence of alternative slates of electors, even though those alternative slates, to the extent that they did exist, were not legitimate.

Both memos claim for the vice president an extraordinary authority—in effect, the power to singlehandedly decide the outcome of an American election.

In short, Eastman was embroiled in an extraordinary effort to create authority for Pence, conferring new powers upon his office, and urging him, on the basis of untrue allegations, to take action that would have overturned a legitimate presidential election. It is impossible to read those memos and not see that Eastman was working to find ways to manipulate the American electoral process for the sake of Donald Trump’s continuance in power. Had Pence participated, it would have thrown the country into a serious constitutional crisis. Had Eastman’s plan succeeded, the results for American democracy would have been devastating.

It is unclear to me whether Eastman himself was engaged in gross delusion or straightforward malpractice, but you would have to be a fool not to see a problem with his actions.

II. Claremont’s Supposed Cancellation

Most members of the American Political Science Association are not fools, and they see the clear and immediate threat that Eastman’s actions posed to American democracy.

And so, when some APSA members noticed that the Claremont Institute was still maintaining ties to Eastman and that Claremont would be featuring Eastman on two panels at APSA’s big annual meeting, they started pushing back. They tweeted. They posted on Facebook and on blogs. They debated the appropriate course of action. People noticed that Claremont has apparently been using its involvement at APSA as a fundraising tool. In the week leading up to APSA’s meeting this year, a few hundred individuals signed an open letter requesting that Eastman and Claremont be ousted from the conference. It seemed all but certain that there would be in-person protests of the Claremont panels at APSA.

Full disclosure: The open letter cited my July essay for The Bulwark about Claremont, and while I was glad to see the letter circulating, I did not sign it. I am uncomfortable with the idea of any kind of ideological test for participants in political science conferences. I am persuaded by Jeffrey C. Isaac’s idea that a censure of Eastman and Claremont would be consistent with APSA’s stated interest in supporting liberal democracy, but that in going further—say, by ousting Claremont permanently from the conference—APSA would run up fast against the competing values of intellectual liberty and free inquiry. (More on that in a moment.)

Now, as any political theorist can tell you, asking radical questions is very different from taking dramatic action, but even so: Weak-kneed liberal that I am, I was hoping for a censure of Claremont and Eastman’s actions, and then careful deliberations about what more to do— something like the associational equivalent of “impeachment but no removal.”

So what actually ended up happening at APSA? This depends a lot on who you ask.

The president of the Claremont Institute, Ryan Williams, described the episode this way in Newsweek on October 1:

Last Friday [i.e., September 24], I made the decision to withdraw the Claremont Institute's program [from the annual APSA meeting] this year after APSA, without explanation, moved all 10 of our panels (and our reception) to a “virtual” format. Though APSA Executive Director Steven Smith would never confirm directly, it became clear that Claremont Institute Senior Fellow John Eastman’s independent role as President Donald Trump's attorney during challenges to the 2020 election was at issue. On July 28, we got word from APSA that two of our panels were being moved from in-person to virtual. There was no mention of why, but the common detail for both was Eastman's presence. When pressed, Smith cited “safety.” When we inquired for specifics, so that we might assess the safety of the rest of Claremont staff and participants in Seattle and prepare accordingly, we got no response. . . . APSA decided to cave to the mob this time, betraying a core principle of academic freedom and republicanism: reasoned debate about even the most controversial political and intellectual topics.

Williams concludes not on an optimistic note but an opportunistic one, remarking that the Claremont Institute looks forward to providing “truly safe spaces for rigorous and open debate” and filling the gap left behind as “legacy institutions of the American academy like APSA grow more insular, ideological and irrelevant to normal citizens.” The same day his Newsweek piece was published, another conservative group, the Intercollegiate Studies Institute, announced plans for a separate conference next year, a few weeks after APSA’s 2022 meeting, “in response to” APSA’s “decision to sideline” Claremont.

Others have been singing a similar tune. Patrick Deneen—a professor in the political science department at Notre Dame University, and author of the 2018 hit Why Liberalism Failed—insists, in a Twitter thread and in an article in the conservative magazine First Things, that what transpired at APSA is “effective banishment” and nothing less than “a political purge” of conservatives: “The professional organization was making a political choice, one designed to banish a political perspective that has been deemed unacceptable.”

Deneen goes even further, arguing that the episode with Claremont demonstrates the close-mindedness of APSA and the academic profession of political science. Through their actions with Eastman, APSA has allegedly shut down inquiry into all fundamental political questions:

[APSA and the profession operate] under the presumption that we live at the end of history, with those most responsible for studying politics having rendered themselves incapable of asking the most important questions with which any genuine study of politics must begin. . . . If one wishes to examine our deepest and most pressing political matters, don’t bother with APSA or much of what remains of academia. This past weekend, the discipline of political science declared itself to be a distinctly partisan arm of liberalism, not a genuine venue for political inquiry.

Now, it is a bit quaint to see Patrick Deneen wax on about free inquiry and intellectual oppression. Not so long ago, he was in Hungary praising Victor Orbán, whose autocratic manipulation of core democratic institutions, including the media, universities, the judiciary, and elections, is well documented. So it is odd to see Deneen now appealing to principles like freedom of speech, thought, and association—essentially liberal premises that, so far as I can discern, he does not himself strongly believe in—to make his case. Nevertheless, in his essay Deneen does make some good points about the need to study fundamental, regime-level questions. The problem is that a) many scholars already do; b) he ignores converse questions relevant to the profession, like “Are there any limits to what a professional group of political scientists living in a modern liberal democracy might tolerate within the confines of their civic association?”

But beyond this, the idea that the APSA/Claremont upset revolved around some negligible disagreement about “perspectives” being deemed “unacceptable” is quite the understatement, and involves a complete collapse of the distinction between thought and action.

Deneen softpedals the Eastman/Claremont matter all the way through the essay. He briefly makes note of Eastman’s memo. But he is much more concerned with the malicious letter-signers and alleged APSA subterfuge than with anything Eastman did. At one point he frames the problem as follows: “[APSA] used one of its unpopular members as the proximate cause for banning an entire organization, the overwhelming majority of whom are focused on their academic work and had nothing whatsoever to do with the events of January 6.”

Does “unpopular member” really capture what is at stake with Eastman?

And does it really make sense to suggest, as Deneen does, that the Eastman brouhaha is a pretext to ban “unacceptable” conservative ideas from APSA? Williams implies much the same thing. But Claremont panels have been offering comparable content for many years now, without ever—to my knowledge—facing a threat of expulsion or censure (though it may be true that Claremont panels have repeatedly been assigned unduly small and hot rooms at the annual conference). Moreover, there are other conservative groups affiliated with APSA: The Federalist Society, the Eric Voegelin Society, the Center for the Study of Statesmanship, the International Churchill Society, Christians in Political Science, and the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation are among the groups that planned panels at APSA this year, while recent years have also seen panels from the American Enterprise Institute and various libertarian organizations. Besides, most APSA conference activity, including that of conservatives, takes place in the panels organized as part of APSA’s disciplinary divisions (this year, APSA’s various disciplines hosted 1,223 panels; Claremont had been slated to host 10). The notion that APSA’s decision to move Claremont’s panels to Zoom amounts to anything like banning conservatism from APSA is laughable.

Patrick Deneen has spent a good portion of his career decrying the hypocrisy of the pretense of liberal neutrality and arguing that liberals have smuggled in controversial value judgments under the guise of mere neutrality. There is some truth to that critique. But in his essay about APSA, Deneen is engaged in something like the inverse problem: He is indulging in a much broader, moralizing allegation than the evidence calls for, and making a grandstanding mountain out of a factual molehill, minimizing the real-world stakes of APSA’s conflict with Eastman while exaggerating the scope and meaning of APSA’s actions.

APSA has yet to release any official statement about the incident. But I reached out to people at the association to learn more. Everyone I spoke with asked not to have their name used, but I did hear a consistent story from multiple people close to APSA’s leadership—a story that contradicts Claremont’s claims, and Deneen’s big theory, in key respects.

The people I spoke with assured me that APSA’s decisions regarding Claremont were not motivated by ideological concerns. They said that the association’s leaders had grown worried about safety given the possibility of protests at Eastman’s panels, in light of his notoriety after January 6th. They said that the decision to move Eastman’s two panels online took place in July 2021, well before the publication of Eastman’s memos in September and the ensuing public criticism and the open letter. They noted that the Claremont organizers later tried to put Eastman back on at least one in-person panel—a key fact that Ryan Williams does not mention in his Newsweek piece (but that is confirmed in this article defending Claremont written by Claremont Washington Fellow Scott Yenor; Yenor claims that some of Claremont’s participants had dropped out because of the conference’s vaccine mandate, and that Eastman was moved only because they were scrambling to fill these vacancies). From the point of view of APSA, this was a bad-faith effort to undermine APSA’s prior decision, and so APSA’s leaders decided, in response to Claremont’s actions, to move all of this year’s Claremont programming online. After that, the Claremont leadership decided simply to cancel everything it had planned for this year’s conference.

If this version of events is right, then there are three important takeaways.

First, APSA is not totally blameless in this affair. APSA arguably overreacted in moving Eastman’s panels online in the first place, and in their subsequent decision-making, too. The organization’s leaders should have been more transparent with Claremont and with the public, because their mode of conduct has opened them up to precisely the kind of charges that Patrick Deneen has leveled against them: of cowardice, lack of transparency, and ideological partisanship. Absent some clear statement—either about safety concerns, or about Eastman or Claremont’s misconduct and loss of professional credibility—it probably would have been better to let the Claremont crowd proceed and face their protesting colleagues. Instead, APSA chose the awkward path of least resistance. As Jonathan Marks writes in his recent book, Let’s Be Reasonable, most professional academics “don’t want no trouble.” My sense is that, for better and for worse, APSA acted true to its deliberative, bureaucratic form. This has left them slightly exposed.

Deliberative bodies that act slowly and ploddingly are always going to be sitting ducks when it comes to unscrupulous bad-faith actors.

Second, even if APSA overreacted, and even if the organization did submit to the heckler’s veto, it also seems clear that the Claremont leadership bears significant responsibility for the blowup. If my APSA sources’ version of events is correct, then Claremont chose not to accept APSA’s decision to move Eastman’s panels online. Claremont tried to work their way around it. And Claremont, not APSA, made the decision to pull out of the conference, shutting down the actual substantive intellectual exchanges they profess to value so highly.

The third point is this: The matter remains unsettled. Claremont claims to have been banned from APSA, but it is still listed as a related group on the association’s website and still boasts of the affiliation on its own website. Is there anything stopping Claremont from crying foul now but then slipping back onto the APSA program next year?

III. Claremont Doubles Down

So far, the American Political Science Association is not speaking publicly. Claremont and its friends, though, have had a lot to say. On October 8, Ryan Williams sent out a fundraising letter in which he praises Eastman to the sky:

Under the excellent leadership of John C. Eastman, our Claremont legal team continues to be the “point of the spear”—always arguing our cases based on originalist, natural law-based principles consistent with the Founders’ Constitution, and not on “international law” or multiculturalist ideology and “tribalism.”

The letter does not mention Eastman’s involvement with the events of January 6, nor does it mention Claremont’s difficulties at APSA. But it is off-putting—if unsurprising—to see the institute invoking Eastman’s name in a funding appeal at the very moment when the institute is claiming it has been censored in the fallout from his actions.

And on October 11, Claremont issued an official statement that goes beyond the APSA controversy to positively defend John Eastman’s good judgment with regard to January 6. On October 11, Ryan Williams and Claremont Chairman (and major donor) Thomas Klingenstein released a statement intended to “correct the record and state the truth” about John Eastman.

Claremont’s latest telling of the Eastman story involves two points of clarification.

First, Williams and Klingenstein say they want to make clear that Eastman did not ask the vice president to overturn the election or to determine the validity of the electoral votes. According to Williams and Klingenstein, Eastman went for the option delineated in section III.d of the long memo, in which Pence would merely ask for a pause in the proceedings. They put it like this:

John advised the Vice President to accede to requests from state legislators to pause the proceedings of the Joint Session of Congress for 7 to 10 days, to give time to the state legislatures to assess whether the acknowledged illegal conduct by their state election officials had affected the results of the election.

It is true that this course of action is one of the less inflammatory alternatives on Eastman’s list. But it still grants—on the basis of Eastman’s strained reading of the Constitution and his bottom-of-the-barrel search for precedent—the vice president a degree of authority over the certification process that Pence himself ultimately decisively rejected.

Moreover, note the sleight of hand in the Claremont statement. Not a single state government—no state legislature, no governor, no state high court—asked to have its slate of electors replaced or changed. None of them endorsed a Republican alternative slate of electors. None of them asked for more time. But Williams and Klingenstein try to obscure that fact by referring to “requests from state legislators” instead of “state legislatures.” According to Williams and Klingenstein, Eastman would have had Pence treat individual, informal requests from state legislators with the same weight as official government decisions. This would effectively empower individual state legislators—there are over 7,000 of them in the country—to derail the orderly certification process. It would allow a vice president to use any request from any individual state legislator, no matter how flimsy or partisan, as an excuse to throw the peaceful transfer of power into chaos. That would cripple the electoral process every four years. In attempting to clear up supposed distortions about Eastman’s memo, Williams and Klingenstein have inadvertently highlighted its radicalism.

In their second point of clarification, Williams and Klingenstein again perform some sleight of hand. In both memos Eastman presents a highly expansive role for the vice president, arguing that Pence would have the authority to settle disputes that might arise about electors. Williams and Klingenstein, however, claim that Eastman told Pence that Congress, not the vice president, has this authority. That may well be the advice Eastman verbally offered, and if so then good for him. But that is not what he argued in his memo to the president, where he claimed that the Constitution makes the vice president “the ultimate arbiter” in such disputes.

Williams and Klingenstein conclude their statement with a lot of fanfare about “deliberate misrepresentations of John Eastman’s advice on these legal and constitutional questions.” They accuse their “malicious domestic political opponents” of slander, and accuse APSA of violating the deeper principles of American constitutionalism by disarming “free argument and debate.” According to Williams and Klingenstein, a “campaign is trying to prevent the Claremont Institute or its scholars from presenting our views.” This is nothing less than a “dangerous escalation in the censorship now threatening American democracy.” The glaring irony here—that they profess to worry about a threat to American democracy while defending the work of a man who wanted to see a democratic election overturned—is apparently lost on them.

The Claremont Institute’s leadership has backed itself into a corner. Straight propaganda and misinformation outlets are dime-a-dozen on the right today. Claremont’s value-added is its perceived intellectual seriousness, which comes from publishing the Claremont Review of Books, organizing speakers and panels at APSA, and hosting conferences and receptions. These days, though, the Claremont Review is not what it once was, and Claremont’s web publication, the American Mind, routinely publishes pieces that damage the institute’s reputation for intellectual integrity. And so their involvement in APSA is one of the few external legitimating elements remaining. Once that is lost, so goes much of the intellectual patina that is the Claremont trademark.

As Jeet Heer notes with respect to the Federalist Society, an organization that has apparently quietly distanced itself from Eastman, “If they continued to host events with Eastman, the Federalist Society would lose their status as a respectable mainstream institution that can be trusted to provide advice to the Republican party.” What the Claremont folks can’t say aloud is that they have an Eastman problem, too—it’s just that it’s a much bigger problem because Eastman is a more prominent figure in their organization.

So Claremont is not going to go down (and by that I mean abide by norms set down by an establishment institution like APSA) without a big to-do and a flurry of indignation. They need to have been wronged. They need to be the free-speech martyrs. They need to be the ones being silenced unjustly, and this must be a sign of terrible oppression to come for all.

Something similar, it seems to me, is going on with Patrick Deneen.

Deneen concludes his First Things essay with a brief diatribe regarding what he sees as the grand stakes in the APSA/Claremont controversy:

This inquiry into the nature of the good regime within existing imperfect regimes is an inherently precarious undertaking, and has almost always taken place at the edges of society—a tradition dating back to Socrates’s challenges to democratic Athens. Today’s academics claim to be the heirs of Socrates, but far more resemble the mendacious Sophists who sought his imprisonment and death by claiming that his questions were too dangerous for the regime to permit.

This is a tortured analogy, since it implicitly likens the Claremont Institute (not to mention Deneen himself) to Socrates (who is traditionally understood to have been humble and fond of irony) and the APSA political scientists to the power-hungry sophists. But sophists are known primarily for putting money and fame ahead of truth. Deneen and the Claremont group—not the political scientists of APSA—are the ones twisting up the truth about Eastman and the 2020 election, not to mention hobnobbing with Viktor Orbán, and Donald Trump, and Josh Hawley, and Mike Pompeo, and Ron DeSantis.

The most haunting thing about the APSA/Claremont saga is how tidily it replicates the broader political dynamics of the Trump era.

On one side, we have John Eastman, who, like the man he was working for, did something reprehensible in the lead-up to January 6, and whose work jeopardized the peaceful transfer of power. Eastman’s friends at Claremont, like the Republican party vis-à-vis Trump, continue to twist themselves into knots trying to defend these actions: They do away with niceties like a regard for evidence and truth, or for any norms beyond strict criminality. The stories they have to tell to justify any of it (about their colleagues and the country at large) get worse and worse. And faced with even modest pushback—in this instance, a less than fully transparent decision to have some professional panels featuring an extremely controversial figure moved to an online format—they flood the zone with faux cries of “Victim!” and “Cancel Culture!” and “Mob!” followed immediately by a fundraising push.

So much for good-faith inquiry and persuasion.

On the other side: many of the country’s political scientists, angered and alarmed by John Eastman’s actions, and concerned about the fate of American democracy. Some of them went too far—asking for too much, too fast, in their letters and blogs, and posting some very mean tweets. Most grappled in earnest with what their patriotism means for their liberal intellectual precommitments, concerns caught up together in the question: “If we don’t draw some lines in the sand, who will?”

It’s a good question.

Correction (October 18, 2021, 2:30 p.m. EDT): A sentence describing a political science conference planned for 2022 has been edited to make clear that the Intercollegiate Studies Institute will be hosting the conference alone instead of with the Claremont Institute.