The Contradictions of Jefferson’s Vision for an American University

His philosophy of education and the messy realities of the democratic-yet-elite school he founded.

The Illimitable Freedom of the Human Mind Thomas Jefferson’s Idea of a University by Andrew O’Shaughnessy University of Virginia, 368 pp., $34.95

Reflecting on a day spent exploring Versailles and dining with French aristocrats in 1778, John Adams concluded that the people of France were simply too decadent for self-government. “The foundations of national Morality must be laid in private Families,” he noted sharply in his journal. “In vain are Schools, Accademies, and universities instituted, if Loose Principles and licentious habits are impressed upon Children in their earliest years.”

Had he read Adams’s journal, Thomas Jefferson would have begged to differ. A year after Adams jotted down his thoughts on schooling and virtue, his Southern compatriot introduced legislation in the Virginia General Assembly to transform the state’s education system. In addition to establishing public elementary schools for all free children, Jefferson’s bill created grammar schools for academically advanced boys—a pool from which the highest-ranking pupils would receive a scholarship to the best university in the state.

The bill failed, but Jefferson’s belief in the power of a college education only grew stronger over time. He never lost the conviction that universities were key to forming the next generation of leaders who could protect the liberal “spirit of ’76” and the American project in republican self-government. After deeming universities like William and Mary and Hampden-Sydney College unsuited to the task, he decided to create one of his own.

In The Illimitable Freedom of the Human Mind, Monticello historian Andrew O’Shaughnessy offers a meticulously researched intellectual history of Jefferson’s vision for what would become the University of Virginia. His narrative highlights the obstacles Jefferson faced and the many compromises he had to make in his quest to create a publicly funded university that claimed free inquiry, rather than institutional religion, as its lodestar.

While recent histories of UVA have centered on the institution’s brutal entanglement with slavery, O’Shaughnessy offers a nuanced rejoinder to the argument that Jefferson’s final intellectual project was designed explicitly to protect Southern slave interests. However, Jefferson’s unshakable optimism proved a brittle shield against the corrupting influences of the slave society in which his university was born. As we debate the purpose of the American university today, the story of UVA’s origins offers an illuminating case study on the promises and limits of what a college education can reasonably accomplish for our republic.

As O’Shaughnessy explains over the course of his book, Jefferson’s design for an institution of higher education was both forward-looking and grounded in his own educational experiences. Decrying the classically centered curricula of schools such as Oxford and Cambridge as turgid and outdated, Jefferson wanted the University of Virginia’s offerings to span the width and breadth of the classics, humanities, and modern sciences, alongside a law school, medical school, and even vocational training in “technical philosophy” for skilled farmers and artisans. As he noted in a draft report for the Rockfish Gap Commission, the body of commissioners charged with developing a plan for the University of Virginia, “The term university comprehends the whole circle of the arts and sciences and extends to the utmost boundaries of human knowledge.”

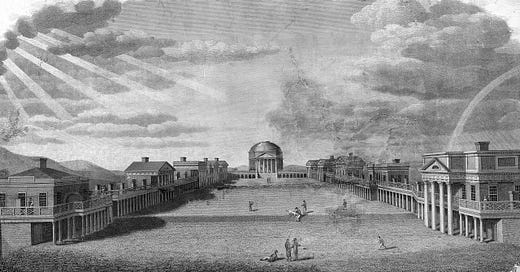

Jefferson also sought to replicate the mentorship he had received as a student at William and Mary under professor of natural philosophy William Small and legal scholar George Wythe. To that end, he created an architectural plan for his university that placed students and teachers in intimate proximity to each other. Students would live in dorms directly connected to classically designed pavilions that housed their teachers and their families. Instead of a church, at the heart of this “academical village” would sit a combination library, lecture space, chemistry laboratory, museum, and planetarium that Jefferson modeled after the Roman Pantheon and dubbed the “Rotunda.”

In addition to placing students in constant contact with their teachers, Jefferson expected the professors he hired not just to be masters of their respective fields, but also to have the ability to teach multiple related subjects and converse intelligently with their colleagues on their work. In this way, Jefferson anticipated our current emphasis on interdisciplinary research and our understanding of the university as an institution that produces and conveys knowledge.

However, there was one subject that Jefferson insisted would not be taught at his university. He forbade the University of Virginia from establishing a department of religion, hiring clergymen as professors, or allowing the study of theology outside the context of other disciplines such as history or philosophy. His 1779 bill to establish a three-tier system of public schools failed in the state senate in the 1780s not just because Virginians were unwilling to raise the taxes required for such an endeavor, but because religious leaders from a variety of denominations protested its lack of support for religious education classes.

As O’Shaughnessy explains, Jefferson’s opposition to religious education stemmed from both a general distrust of organized religion and a tendency to conflate certain denominations with Federalism. He especially viewed Presbyterianism as “an inherently authoritarian religion with its doctrine of the elect and its belief in predestination,” and believed that any educational institution headed by members of the denomination (such as Yale, whose president actively campaigned against Jefferson in the Election of 1800) was incapable of instilling sound republican principles in its students.

Determined to use his retirement years to build a university, Jefferson joined the board of the shell “Albemarle Academy” in Charlottesville in 1814 and transformed it into the foundation for the University of Virginia through the Rockfish Gap Commission. He then worked with Joseph Carrington Cabell, an ally in the state senate, to block a bill sponsored by Federalist Charles Fenton Mercer that would have used an existing state educational fund to create a centralized system of primary schools under the direction of the state government, leaving little funding for a new state university. O’Shaughnessy notes that Jefferson’s resistance to Mercer’s bill did not stem from a lack of concern for elementary education; rather, he was opposed to the way the bill placed these schools beyond local control. That Mercer was an Episcopalian—another denomination he considered threateningly powerful, and which already controlled William and Mary—stoked Jefferson’s determination to fight this perceived incursion against the separation of church and state.

O’Shaughnessy largely leaves it up to the reader to decide whether Jefferson was wise to mobilize his political power to fund a university rather than fighting for his “ward republics,” as he called the foundational tier of his public education plan. However, by leading the reader through the many decades that Jefferson spent outlining the need for a secular university in his home state, O’Shaughnessy deflates recent arguments that sectional tensions over slavery in the 1820s were the primary impetus for the university’s founding. Jefferson certainly wrote impassioned letters in the wake of the Missouri Crisis warning that Southern students studying in the North were “imbibing opinions and principles in discord with those of their own country.” However, O’Shaughnessy argues that the “principles in discord” he feared more than threats to Southern slavery were Federalists using the crisis to regain political power.

Jefferson’s blinkered perspective on the Missouri Crisis exemplifies the elder statesman’s capacity for seemingly willful shortsightedness, and this quality may account for the many contradictions that characterized the university at its outset. Some of these contradictions were more benign than others. For all his emphasis on training good republicans, Jefferson gave students unprecedented freedom over their course selections. Moreover, he almost exclusively hired foreign professors over Americans (a decision John Adams criticized) and deferred to them on their syllabus selections. Although Jefferson was, in O’Shaughnessy’s estimation, “more dogmatic about the teaching of religion than any other subject,” UVA’s reputation as a secular university enabled it to attract professors from a wide range of religious backgrounds, such as Joseph Sylvester, the first Jewish professor in the United States. But while he lauded his university as a place where “we are not afraid to follow truth wherever it may lead,” Jefferson shamefully failed to include any antislavery texts in the school’s library. He also restricted the teaching of Blackstone’s Commentaries and Hume’s History of England in the law school, since he deemed these texts baleful Tory corruptions.

The contradiction that proved most damaging to the University of Virginia was the unmanageably ruinous culture of the school’s elite student body. Despite receiving state funding, the exorbitant costs of bringing Jefferson’s intricate designs to life meant that UVA became the most expensive university in the country in the early nineteenth century. It also discarded Jefferson’s ideal of providing scholarships for poor students. As a result, only the sons of the wealthiest families could afford to attend, and they brought with them the unrestrained arrogance, petulance, and violence of Southern slave and honor culture.

Jefferson himself observed in his Notes on the State of Virginia how the moral perversions of slave-owning were passed from father to son: “[T]he child looks on, catches the lineaments of [his father’s] wrath, puts on the same airs in the circle of smaller slaves . . . his worst passions [are] thus nursed, educated, and daily exercised in tyranny.” Pulling from the minutes of faculty meetings, O’Shaughnessy details copious accounts of student binge-drinking, rioting, dueling, making threats against faculty, and perpetrating horrific physical and sexual assaults against UVA’s enslaved workers—offenses that regularly marred each academic year. While Jefferson optimistically estimated that a third of his university’s students were diligent and hardworking learners, the academic sanctuary that he created in central Virginia proved too weak a mold to reshape the aristocratic students whose formative years were spent resisting any form of authority. Many UVA students also arrived with a checkered elementary education, leaving them unprepared for college-level work. Compounding all this, Jefferson hired professors based on their academic achievements, not their teaching experience. As a result, professor of moral philosophy George Tucker later reflected, “our want of skill in the management of young men was manifest.”

One of O’Shaughnessy’s few mistakes in The Illimitable Freedom of the Human Mind is his failure to foreground the extent to which almost all of UVA’s early faculty also participated in the slave system. Although many of them disapproved of slavery in theory, leading professors and members of UVA’s Board of Visitors such as Joseph Carrington Cabell, John Hartwell Cocke, professor of medicine Robley Dunglison, law school chair Francis Gilmer, and George Tucker were all slaveowners. However, O’Shaughnessy is not cagey about the central role slavery played in the university from its founding. As his narrative makes clear, enslaved workers leveled the ground for the university’s cornerstone, “acted as carpenters, bricklayers, painters, stonemasons, boatmen, and blacksmiths” during the construction of the Rotunda and the Academical Village, and fed, cleaned for, and waited on professors and students. While The Illimitable Freedom of the Human Mind spends less time detailing the lives of UVA’s enslaved community than other recent works on the school’s history such as Alan Taylor’s Thomas Jefferson’s Education, O’Shaughnessy’s critical focus on Jefferson’s ambitions for his university makes plain how painfully those ambitions fell short in reality.

"What is a legacy?” Alexander Hamilton asks at the end of Lin Manuel-Miranda’s eponymous 2015 musical. “It’s planting seeds in a garden you never get to see.” Jefferson meant the University of Virginia to be his final legacy. He died in 1826, barely a year after UVA opened its doors to its first turbulent cohort of students. And despite its early tribulations, UVA did succeed in training a new generation of Southern leaders—including many that turned against the Union during the Civil War.

O’Shaughnessy bookends his history of UVA with the story of a different kind of alumnus. As part of UVA’s first class of students, Henry Tutwiler dined with Jefferson at Monticello and used his university education to become a professor of ancient languages at the University of Alabama. He founded a progressive academy for boys that, remarkably, also allowed admission for girls; helped to establish a chapter of the American Colonization Society in Tuscaloosa; and broke the law by teaching the enslaved members of his household how to read and write. He cited Jefferson as an influence on his antislavery views and his love of education, the latter which he argued could not be denied to anyone who hungered for it.

O’Shaughnessy unfortunately fails to mention that, like most UVA students and alumni, even Tutwiler was a tepid supporter of the Confederacy when war broke out in 1861. However, 64 students, 26 alumni, and 5 instructors transcended Tutwiler’s countercultural example by fighting as soldiers or lobbying as civilians on behalf of the Union during the Civil War. As UVA’s Nau Center for Civil War History details, their elite education meant that many of these “UVA Unionists” served in leading positions in the military and political office during and after the war. Some students, like Joseph Cabell Breckinridge, left UVA’s grounds to fight at critical encounters at Shiloh and Corinth, while alumni like Henry Winter Davis and Benjamin F. Dowell drew upon the legal training they received at UVA to assist in passing the Thirteenth Amendment and supporting civil rights for African Americans.

Much ink is expended today about what universities should be teaching, and how. Do we need stricter curricula, a greater emphasis on diversity, more funding for cutting-edge research, or a return to the Great Books? Many thoughtful people argue that controlling the university and aspiring for a certain kind of student formation is the key to curing our social and political malaise. However, the story of UVA’s susceptibility to the dominating culture of its era certainly offers a cautionary tale to those who might invest too heavily in the concept of the alma mater. As John Adams pointed out, so many of our formative years are spent germinating in fields far away from the university campus, and virtue must be planted early if it is ever to take root.

That is not to say that universities shouldn’t experiment with reform, or to deny that academia is in crisis. Even so, our complex and pluralistic society needs many different kinds of universities, and we should not lose sight of the value that comes from institutions that simply do their best to expose their students to the widest expanse of human learning. Tutwiler, Breckinridge, Davis, and Dowell’s pursuit of truth delivered them to very different conclusions from those of many of their fellow UVA students. They may have been a minority at the school, but their lives best represented the promise of Mr. Jefferson’s university. While it’s never a guaranteed outcome, a university education that can nurture the seeds of lifelong intellectual curiosity and independence of thought might provide just the sort of nudge that a person needs to reorient their life towards a better calling.

Culture-fueled controversy has not ceased to dog UVA over the course of its lifetime—it certainly didn’t when I was a student there. But over time, UVA as an institution has largely upheld some of the best elements of Jefferson’s vision: high educational standards, careful mentorship of its students, and a commitment to free speech and debate. I will never forget the feeling of walking across the Lawn on cloudless nights, mind abuzz from a “feast of reason” in an evening lecture or undergraduate seminar. Looking up at the stars over the curve of the Rotunda, it was hard not to feel like you, the world, and everything else contained within it was nothing short of illimitable.