The Crazy, and True, Story of How America Got the Electoral Count Act

Hayes, Tilden, and the most dangerous election in American history.

Read Part 1:“The Electoral Count Act Is a Zero-Day Exploit Waiting to Happen.”

Imagine this scenario: After an emotional and hard-fought campaign, the Democratic candidate wins a majority of the popular vote. Claiming fraud, Republican election officials in four states throw out thousands of votes. These four states return two sets of electoral votes—one for the Democrat and one for the Republican—each of which has been signed by different state officials. The whole mess ends up in Congress which, in the midst of ongoing threats and street violence, is unable to resolve the situation as the clock ticks down to Inauguration Day.

Actually, you don’t have to imagine it. This is how Rutherford B. Hayes was elected as the nineteenth president of the United States.

Prior to the passage of the Electoral Count Act, counting electoral votes was a recurring problem and Congress had to pass a joint resolution every four years describing how the count would be handled. Serious efforts to come up with a more robust system began in 1873 after the near-disastrous 1872 election in which Ulysses S. Grant faced Horace Greeley.

Greeley is more famous for saying “Go west, young man” than he is for running for president, but he has the distinction of being the only presidential candidate in history to die after the election but before the electoral votes were cast. The result was electoral mayhem. Greeley’s electoral votes were split between four candidates. Greeley himself received three electoral votes which Congress declined to count on the grounds that Greeley, now being dead, did not qualify for the presidency. Congress also rejected the entire slates of electoral votes from Louisiana and Arkansas.

Fortunately, nothing much was at stake. Grant had handily won the election, so this drama was mostly of academic interest. Nonetheless, the balloon was now up and it was evident that the ad hoc system used for counting electoral votes was no longer adequate.

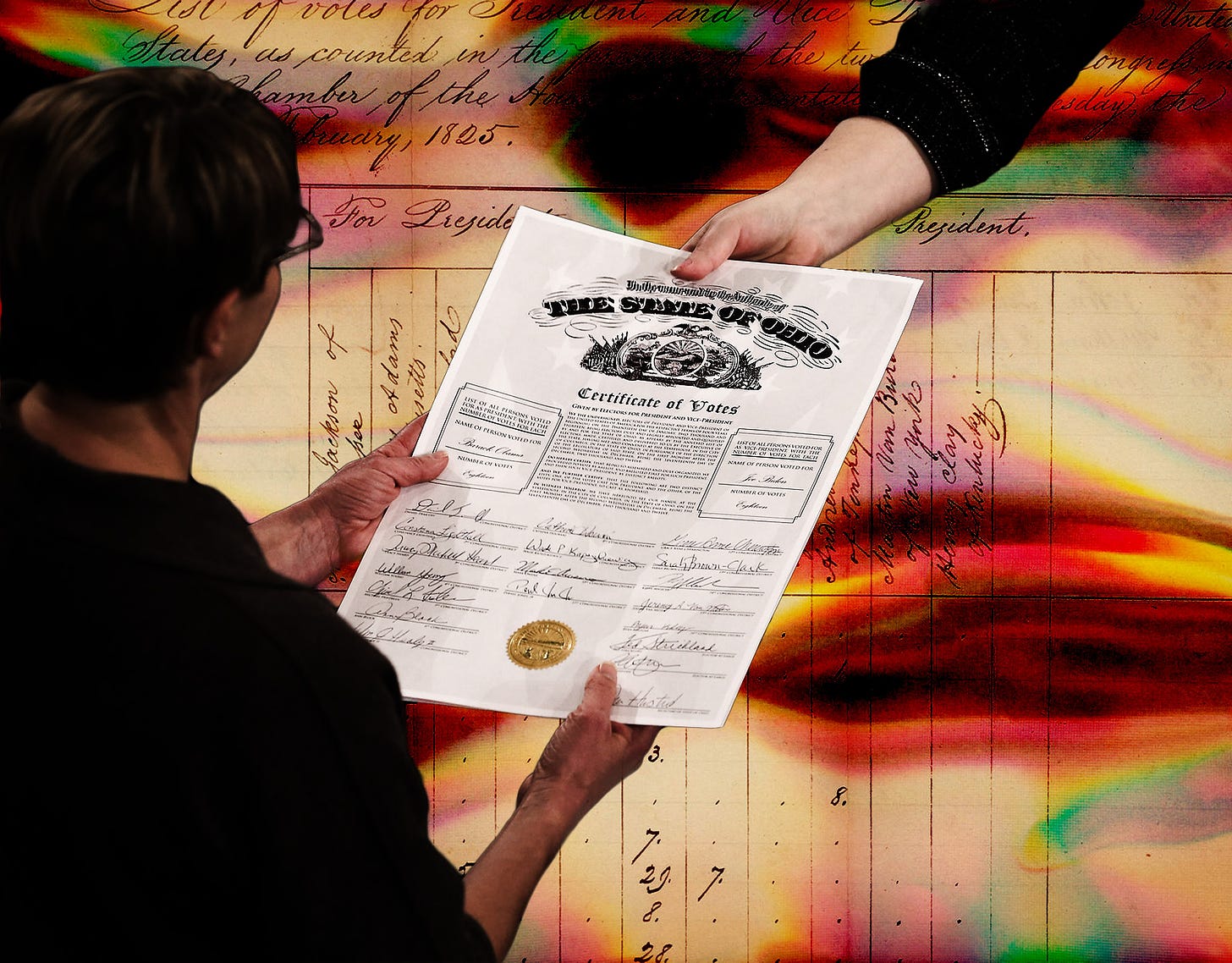

In 1876, Rutherford Hayes, a Republican, faced Samuel Tilden, a Democrat, in the worst presidential election—so far—in American history. Tilden won the popular vote by a three-point margin. It took 185 electoral votes to win and Tilden had 184 clear votes, while Hayes had 165. Tilden appeared to have won Florida, South Carolina, and Louisiana but allegations of fraud and claims that Republican voters had been intimidated by threats of violence resulted in each of those states sending two sets of electoral votes to Congress, one for Hayes and one for Tilden.

In Oregon, presidential electors were directly elected. The top three vote-getters all favored Hayes but one of the electors, a postmaster, was legally disqualified because he held a position of trust or profit under the United States. The governor, a Democrat, appointed the next highest vote-getter, who favored Tilden, as a replacement. In the end, Oregon sent two sets of electoral votes to Congress, one with three votes for Hayes and another with two votes for Hayes and one vote for Tilden.

Not great.

And on top of that, there were objections to counting the votes of six additional states, which had submitted single slates of electors. With Republicans in control of the Senate and Democrats in control of the House, the joint resolution Congress had passed to govern the electoral vote count was wholly inadequate to deal with the ensuing chaos. To make matters worse, the threat of violence was spreading—“Tilden or Blood” was a popular slogan—and shots were fired at Hayes’s residence. In an effort to cut this electoral knot, Congress passed a law on January 29—presidents were inaugurated on March 4 back then—creating a special election commission to sort out the disputes regarding multiple slates of electors.

The commission was explicitly partisan. Made up of 15 members, it consisted of 3 Democrats and 2 Republicans from the House, 3 Republicans and 2 Democrats from the Senate. The commission also included 2 Republicans and 2 Democrats from the Supreme Court who, between them, were supposed to agree on a fifth Supreme Court justice to act as the final member of the commission. (There may not be Democratic or Republican Supreme Court justices in 2022 but there certainly were in 1877.)

The four Supreme Court justices settled on the Court’s one political independent, David Davis. In what may be one of the greatest political own-goals of all time, the Democrat-controlled Illinois legislature immediately appointed him to a vacant Senate seat in an attempt to secure his support for Tilden’s election. Davis, however, promptly resigned from the Supreme Court and took up his Senate seat. At which point the four remaining Supreme Court justices were forced to appoint someone else to Davis’s spot on the commission—and all of the remaining justices were Republicans.

The commission finished its work on February 27. All disputed electoral votes were awarded to Hayes and every vote was 8 to 7.

This straight, party-line vote in favor of Hayes’s election is only part of the story. In what became known as the Compromise of 1877, the electoral count was finally completed and Hayes elected president in the early hours of March 2 in return for a package of political promises hammered out between Democratic and Republican party leaders that included finally ending Reconstruction and handing political control of Louisiana and South Carolina to the Democrats.

There’s a point to this extended history lesson. Congress spent another decade debating the best way to count electoral votes before enacting the Electoral Count Act of 1887. To understand what the ECA is designed to do and whether it’s a good system for determining the winner of a presidential election today, we must understand the milieu in which it was written and how Congress viewed the problem of counting electoral votes.

First, it’s clear the Congress’s greatest concern was ensuring that there was some mechanism in place to resolve disputes and ensure that somebody, anybody, could be elected president. The elections of both 1872 and 1876 raised the specter of insoluble electoral counting disputes that might make it impossible to elect a president at all, especially when control of Congress was split between the parties.

Second, electoral count disputes in the nineteenth century often suffered from the “fog of election.” When there were allegations of fraud in South Carolina, or multiple slates of electors certified in Louisiana, it could be difficult and time-consuming to determine exactly what had happened. On top of that, both the legal system and the body of election law it enforced were far more rudimentary.

Finally, in the early nineteenth century, counting electoral votes was viewed as a political process, rather than as a ministerial or legal one. The consensus was that removing partisan considerations from electoral vote counting was impossible. As one congressman observed in 1882, “[It has been] demonstrated that, whether in a legislative body or in a judicial tribunal, we shall find judges and legislators on the side of their party—not always; but it is a tendency of human nature. I am not attacking anybody; I am not attacking the providence or wisdom of almighty God that has created us with our feelings of prejudice and sympathy.”

Consequently, backroom political horse-trading was the order of the day to an extent that would probably get you arrested if you tried it now. There’s a reason why the legislation that created the Electoral Commission in 1877 was so careful to choose its Supreme Court justices by party affiliation.

The Electoral Count Act of 1887 is a product of its time. It is not a hallowed piece of constitutional furniture. Rather, it’s an ungainly compromise that reflects the concerns of the people who drafted it and the political realities of 1887.

Those concerns and realities no longer reflect our own. Just like the election of 1872, the election of 2020 has put us on notice that our current system of counting electoral votes is no longer tenable. And we know that the flaws brought to light in the ECA by the 2020 election have made a constitutional crisis a question of when, not if.