The Dugina Killing Aftermath

The rabbit hole deepens: Was it the Ukrainians? An FSB plot? Kremlin infighting?

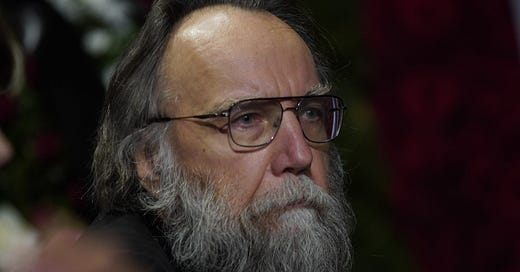

Less than a week after the car bombing that killed Darya Dugina, the 29-year-old daughter of Russian ultranationalist guru Aleksandr Dugin and a rising far-right star, on a highway outside Moscow, the tale grows more twisted. There’s an alleged Ukrainian female killer named by the FSB (the successor to the Soviet KGB). There’s a ham-fisted attempt by the Kremlin to turn Dugina into a martyr. There are hints from members of Russian officialdom that retaliation could include assassinations in foreign capitals. And there are new revelations including an uncannily timed Telegram post by Dugin on the day of his daughter’s death.

Working with astonishing alacrity, the FSB announced on Monday, just two days after Dugina’s assassination, that it had cracked the case: The suspect was 43-year-old Ukrainian citizen Natalia Vovk, acting on assignment from Ukrainian special services. According to the FSB, Vovk had arrived in Russia on July 23 with her 12-year-old daughter and had been watching Dugina for a while, even renting an apartment in the same building. After the bombing, she had absconded to Estonia.

Pro-Kremlin Russian media quickly amplified the report, declaring that the alleged killer was a servicewoman in the Azov Regiment, the controversial force with reported (and disputed) far-right or even neo-Nazi ties whose fighters the Russians are planning to put on trial after their capture at Mariupol. In fact, a Russian hacker group styling itself NemeZida (Nemesis), which posts the personal data of Ukrainian military personnel online, had listed Vovk in its database back in April and posted a copy of what was said to be her Azov ID.

Among independent Russian journalists, the FSB version of events was met with near-universal skepticism and derision. (Even some not-so-independent journalists echoed the skepticism: Nationalist blogger and RT pundit Yegor Kholmogorov wrote on his Telegram channel, “I think this is a lie. For understandable reasons, but still, this is wrong.”) A few people joked that, judging by the speed of the investigation, the murder must have been solved before it happened. Many pointed out a particularly jarring incongruity: The killer had apparently entered Russia in a highly conspicuous Mini Cooper SUV with “Donetsk People’s Republic” license plates, then traded them for even more conspicuous Kazakhstan license plates, and then for Ukrainian plates which she used when leaving the country. She was, moreover, apparently able to cross the border twice under her real name despite being known—or at least listed in a Russian database—as a fighter in Azov, officially classified as a terrorist organization in Russia. “If that’s the case,” wrote one Russian Facebook user, “then Russia has the world’s most liberal border policies.”

Others, such as Amnesty International researcher Oleg Kozlovsky, pointed out the Quentin Tarantino-like plot: a female assassin going out on the job in a stylish SUV, 12-year-old daughter in tow. Kozlovsky thought that the real explanation was obvious: the FSB looked at the list of attendees at the patriotic festival where Dugina had spent her final hours before getting blown up, found a Ukrainian citizen who left the country immediately afterward, and picked her as a convenient scapegoat. However, Vovk’s listing in the NemeZida database as an Azov fighter back in April throws a wrench into that theory.

Was Vovk selected, as some Russian observers have suggested, in order to pin Dugina’s death on Azov and convincingly label the group as terrorists during the upcoming trial of Azov fighters? Maybe, though it’s notable that the FSB statement did not mention the Azov connection and some Kremlin-controlled outlets seemed to question it. On August 23 the Russian propaganda site RT posted video interviews with people who were billed as Vovk’s mother, father and cousin. The putative father said that Vovk had gone to France and Poland in search of work, then returned to Ukraine and enlisted in the armed forces because the pay was good, but suffered from health problems and quit army service on the first day of the war. The putative cousin claimed that Vovk’s son Danila was forcibly recruited to serve in the Ukrainian army but Vovk had managed to “rescue” him. The RT article reported that the family denied any connection between Vovk and the Azov Regiment, even claiming that she had always spoken of Azov in disparaging terms; but there was no video showing any family member making these statements. The article also suggested that Vovk may have been blackmailed into participating in the Dugina murder plot.

In other words, the Vovk story, like so much else in this saga, is a tangled mess. But one notable aspect of the FSB theory is that it implies Dugina, not her father, was the principal target of the assassination. This detail has stoked further skepticism: Despite being something of a rising star on the Russian Orthodox ultra-right, the dead woman had had a relatively low profile in the mainstream Russian media.

The “National Republican Army”—an alleged underground organization which exiled, Kyiv-based former Russian parliament member Ilya Ponomarev has claimed contacted him to take credit for Dugina’s murder and other terrorist acts intended to overthrow Vladimir Putin’s regime—remains as much of an enigma as Vovk. Few if any serious Russia-watchers believe the resistance group is real; one obvious explanation is that it’s an FSB provocation intended to frame dissidents for terrorism. Contradicting this theory: the fact that it has gotten virtually no play in the Kremlin-controlled Russian media and that the group’s manifesto, publicized by Ponomarev, is couched in the language of Russian patriotism. (Given the tenor of Russian propaganda these days, a phony resistance/terror group concocted to discredit the opposition would probably sport a rainbow flag with a swastika.)

Notably, after the FSB announcement naming Vovk as a suspect, Ponomarev obliquely suggested to the Russian-language site Meduza that the mysterious Vovk did have some connection to the Dugina assassination and that the National Republican Army had helped her get out of Russia. On her livestream, Russian investigative journalist (and fellow expatriate) Yulia Latynina noted that Ponomarev was thus appearing to give de facto validation to the FSB theory of a “Ukrainian trail” in the bombing. What gives? Could Ponomarev—who Meduza notes is a somewhat shady character with onetime ties to Kremlin insiders—be an FSB mole? Or is he, as Latynina and some other commentators have suggested, a grifter trying to sell a good story?

And so the mystery—who was plotting to kill whom, and why?—remains. Meanwhile, Putin posthumously awarded Dugina the Order of Courage “for courage and dedication while performing her professional duty,” and her wake at the Ostankino television center became a patriotic event where media personalities and Duma deputies extolled her dedication to duty, country and Orthodoxy and praised her as a “warrior.” But at least so far, the theory that Dugina was killed in a Kremlin-run operation to whip up popular indignation against Ukraine and rally the public around a martyr for Russia doesn’t seem to pan out. Her wake did not get massive play in the media: The federal Channel One aired two relatively short segments, five and seven minutes, in its morning and evening broadcasts. There were no huge crowds; Channel One’s morning segment mentioned “hundreds” of people and the evening broadcast mentioned “thousands,” but the first estimate seemed more accurate judging by the video footage. The Duma members who spoke at Dugina’s funeral were decidedly second- or even third-tier figures: Sergei Mironov from the loyal opposition party, A Just Russia, and Leonid Slutsky from the late Vladimir Zhirinovsky’s “Liberal Democratic Party of Russia.”

If your brain feels scrambled by this trip down the rabbit hole, try this on for size: Just hours before his daughter’s death, Dugin posted on his Telegram channel a screed that implicitly criticized the Kremlin for not being radical enough in breaking with the prewar status quo, which he predicted would be dead in a few months.

The desperate resistance of Kiev’s Atlanticist-Nazi regime requires Russia to make substantial—drastic—internal changes. Structural, ideological, personnel-related, institutional, strategic. . . .

The Commander-in-Chief said: we haven't really started yet. Now we'll have to start, whether we want to or not.

For the first six months, we were able . . . to conduct the special operation without fundamentally without changing anything in Russia itself. So far, the changes are cosmetic, and even completely inappropriate and unnecessary elections were held on schedule. It’s as if nothing was happening. But it’s happening. . . .

It seems to me that at the start of autumn, this awareness of the need to put the country on a new track will be quite clear. . . . I understand that the state is used to ruling as it did before, more or less effectively, for 22 years. But that time is past. ... Now the question is not whether or not the state will want change—specifically patriotic change, conservative-revolutionary, if you will. Such change is simply inevitable. . . .

The special operation is now more important than the state in its subjective dimension. With the beginning of the special operation, the regime of history itself has irreversibly changed: a new ontological vector has appeared, which cannot be dissolved by arbitrariness or decree. The mighty forces of history came into play, the tectonic plates shifted.

Let the old regime bury its dead. A new Russian time is coming. Inexorably. Dugin’s diatribe, to which Latynina drew attention on her livestream, is remarkable in its frank assertion that Russian power structures are in for a drastic overhaul. A lot of powerful people could take that personally.

Obviously, this doesn’t mean that the car bomb was a message to Dugin in response to his Telegram post from a few hours earlier. But it seems more than likely that Dugin was not merely expressing his personal brand of crazy but channeling the view of a faction of “hawks” in Russian government structures. If so, that brings us back to the theory of New Times editor Victor Davidoff (which I mentioned in my first article on Dugina’s assassination) that the bombing is a strike in a war of “Kremlin towers,” intended either to kill Dugin or to send him a warning.

Former KGB officer Sergey Zhirnov, who once worked with the intelligence agency’s “Illegals’ Directorate” familiar to many people from The Americans and who currently lives in France, voiced the same theory in a YouTube interview with Latvia-based journalist Vadim Radionov: the most likely explanation for the murder, he said, was “infighting” among the restive elites increasingly unhappy with the fiasco of the war. If so, this episode could be a sign of coming intra-elite conflict and regime instability.

Zhirnov also mentioned the creepiest theory of all: that Dugin himself helped orchestrate his daughter’s murder in order to boost his own prestige as a patriot, both as a presumed target of the hit and as the bereaved father of a young patriotic martyr. Of course, that’s pretty far-fetched even for Dugin, who seemed genuinely distraught at the wake.

“Everything about this case is strange,” as Zhirnov put it—and it is likely that we’ll be left with another Russian mystery. That Dugin exhorted the old regime to “bury its dead” on the day of an explosion that would leave him to bury his own daughter is just one of those eerie coincidences that makes life—especially life in the 2020s!—stranger than fiction.