The Gang of Ten and the Challenge of Bipartisan Budgeting

The center of the Senate holds a great deal of power. Why not use it to fix real problems?

Could the Gang of Ten—the loose bipartisan coalition of centrists in the Senate (with an elastic membership that changes based on the topic under consideration)—bring order and discipline to today’s otherwise chaotic federal spending and revenue decisions?

They have real clout when they act in concert, as demonstrated in the infrastructure deal they brokered last year and many in the group are now negotiating reforms to the Electoral Count Act. But the partisan divide on overall spending, taxation, and deficits is wide, and thus particularly difficult to bridge. Cross-party deal-making hinges on the willingness of the GOP participants to buck their party and raise revenue in exchange for Democratic support on spending restraint. If that were a possibility (which, to be clear, there is no evidence that it is currently), there would be ample room to strike principled compromises.

The need to shake up the status quo is obvious. Washington careens from one budget-related crisis to another, with many of the problems self-inflicted. It has been years since the government operated under a multi-year fiscal plan. Caps on appropriated spending—a feature of the process for most of three decades—have expired, and neither party is calling for their return. Discretionary spending for 2023 and beyond is thus completely up for grabs and likely to be decided without regard to larger debt or deficit goals. Further, many important tax and spending provisions are scheduled to expire in the coming years, including the tax rates adopted in 2017 and expanded subsidies for health insurance enrollment enacted in 2021.

Pressure to extend both, fully or partially, will be immense but hard to achieve outside of a bipartisan negotiation.

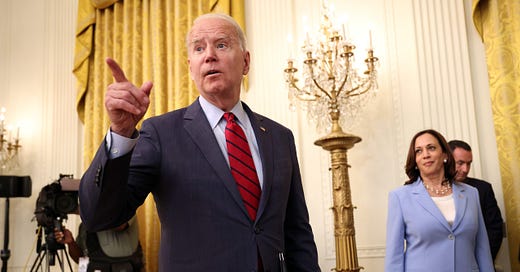

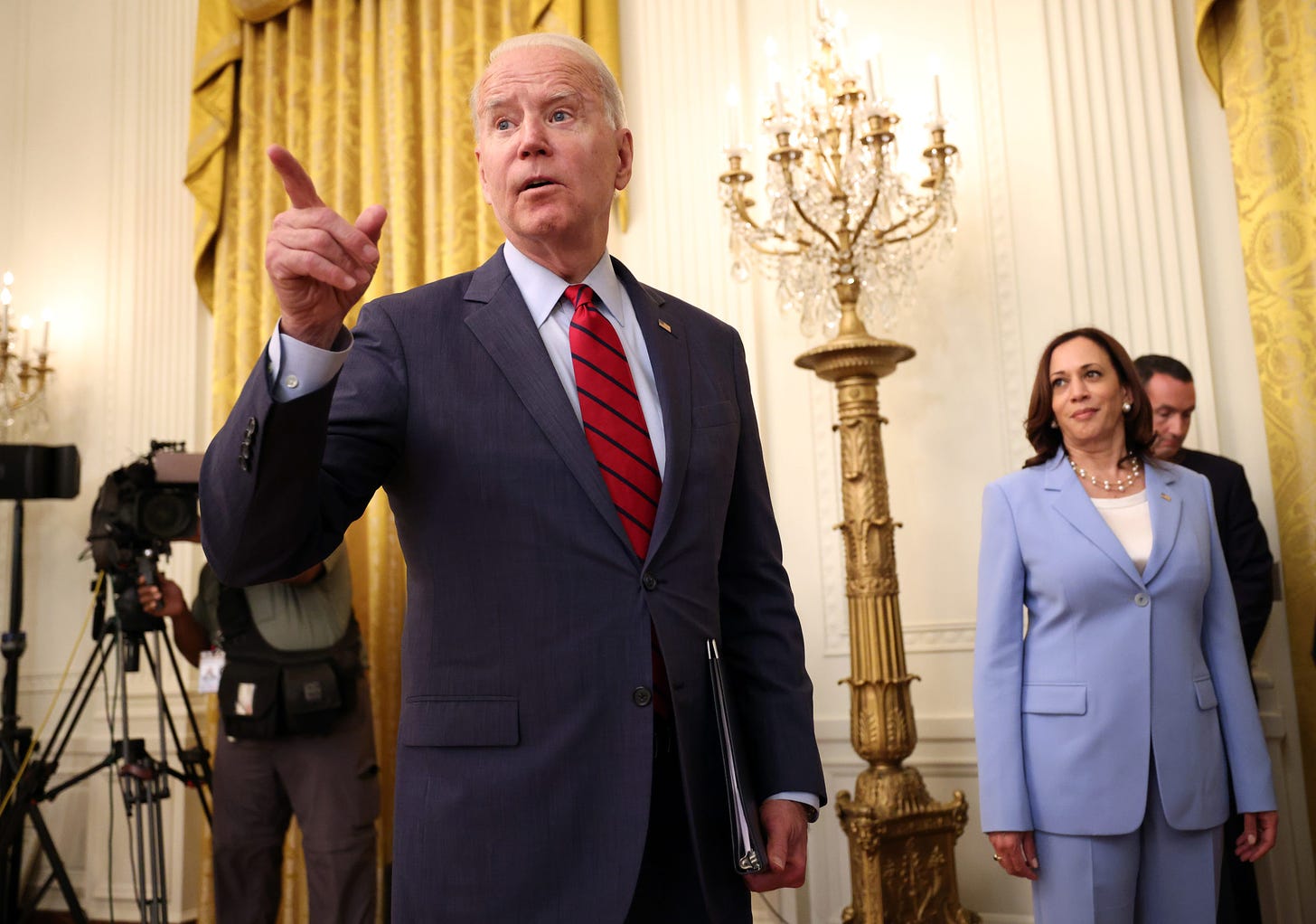

The damage from decades-long neglect of basic fiscal planning now extends far and wide. Social Security and Medicare are spending through their reserves at alarming rates. Medicare’s Hospital Insurance trust fund is projected to be depleted in four years and Social Security’s two trust funds will be insolvent in just over ten. The Biden administration has yet to engage Congress on these questions.

Then there is the debt outlook, which has never been worse. The federal government has embarked on a borrowing spree that is without precedent in peacetime. The Congressional Budget Office projects federal debt, now at about 100 percent of GDP, will rise to over 200 percent by mid-century. At the end of 2008, it stood at less than 40 percent of GDP. Over the next decade alone, the government is set to run a cumulative deficit of over $15 trillion according to baseline projections from the Biden administration.

For now, the spotlight in the Senate is not on the centrist cabal but on two of its Democratic regulars—Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema. They are the holdouts on the Biden administration’s Build Back Better plan, which Democratic leaders still hope to pass on a partisan basis. It is possible such a measure will come together, but hardly assured.

It is also not Manchin’s preference. He has made it clear for months that he would rather engage with Republicans on a compromise bill. He is a fiscal hawk, which should make him an ideal partner for deal-making in the eyes of Republicans. However, recently, he also stated an openness to revisiting a Democratic-only measure because of GOP obstinance over tax hikes. He believes the wealthy and profitable companies should pay more and believes only Democrats will take that step.

Manchin is reading the GOP correctly. Ever since George H.W. Bush broke his no-new-taxes pledge, Republicans have made opposition to net tax hikes a red line they will not cross. Even in January 2013, when Sen. Mitch McConnell negotiated a tax deal with President Obama, the resulting hit on upper income households had to be sold as resulting from expiring tax cuts, not rate hikes.

While that claim was a stretch, there is nothing wrong with the GOP jealously guarding its tax-cutting brand. The country benefits when the two parties compete for support based on diverging fiscal priorities.

But governing in a democracy also requires compromise, especially when the margins in Congress are narrow. Otherwise, diverging priorities create paralysis and problems fester and become more acute—and perhaps insoluble.

Many Democrats have their own red lines that complicate negotiations, especially with respect to Social Security and Medicare, but some adjustments are still possible. In 2011, then-Vice President Biden worked with GOP Majority Leader Eric Cantor on a draft deal that included modest entitlement changes. Both parties have moved further away from the political center over the past decade, but it is not naïve to think some Democrats are still open to a good-faith negotiation.

It is not necessary, or realistic, to expect the Gang of Ten to tackle the entire fiscal challenge. These problems are too big and varied to address all at once. But a small deal would help and could lay the foundation for future progress.

A good start for negotiations might be spending caps for the remaining two years of Biden’s term along with specific revenue increases (perhaps focused on stronger enforcement and the closing of loopholes) and entitlement spending adjustments that would narrow future deficits by a few hundred billion dollars.

The benefits of deal-making would extend beyond the substance of the agreements because they would demonstrate that Congress remains capable of producing reasonable compromises on contentious matters of actual importance.

The Republican participants in the Gang of Ten represent the very small (and shrinking) wing of the party that has not succumbed to the Trumpian fever of recent years. They should see making the nation’s democratic institutions function as intended as an important goal.

At the same time, they would have to know that making a deal with Democrats would carry political costs, too. Working with Manchin and other Democrats on tax and spending matters would further alienate them from the rest of the party, and thus expose them to primary challenges.

So be it. As matters stand today, the GOP is mostly a destructive force in American politics. The elected Republican senators who understand this—and privately despair of it—could help point their party in a healthy direction while also addressing issues of deep importance to the nation and staying true to their principles.

The Gang of Ten is aware of its unique position, and power, in a hyper-partisan Congress, but, so far, it has avoided topics that carry substantial political risks (the infrastructure bill was real spending matched by not-so-real offsets). Wading into major budgetary questions would represent a different level of controversy. One could understand if there was reluctance. But it would be disappointing all the same.