The GOP Is Abandoning the American Idea

Do we still hold the proposition that “all men are created equal” to be self-evident? The party of Trump is turning instead toward the idea of the Confederacy.

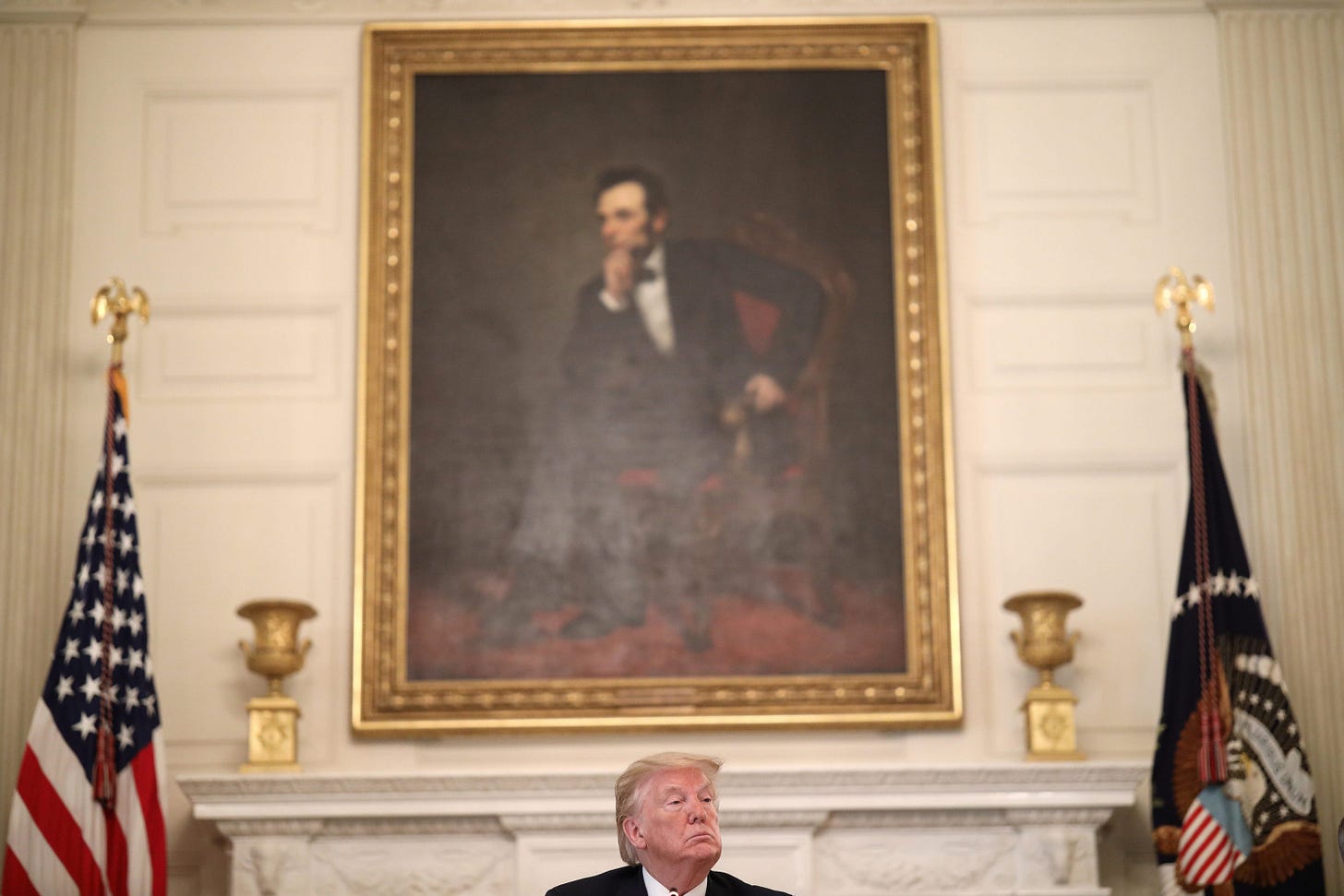

The Republican party was founded in 1854 as an anti-slavery party dedicated to the principles put forward in the Declaration of Independence—particularly the “self-evident” truth that “all men are created equal.” Donald Trump’s Republican party is today abandoning this idea—what we often call the idea of America—for the idea of the Confederacy.

This may appear absurd at first glance. It’s not like the “stars and bars” have been flying over 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. And it’s hard to believe that this president, who seems driven by vanity and impulse rather than ideas, has even the vaguest sense of the history of the Confederacy. I’m not suggesting he does. Yet if we’ve learned anything about his mind over the last four years, it’s his penchant for racial and ethnic division. He seeks to exclude those he doesn’t think belong, for racial and ethnic reasons, from the promise of America. He’s even told American citizens of color to go back to their own country—to “the totally broken and crime infested places from which they came.” It happens they came from America.

When I say that the Republican party is embracing the idea of the Confederacy, I mean that it is embracing what the Confederacy stood for. If the idea of America was, as the first Republican president Abraham Lincoln put it in his Gettysburg Address, that this is a nation “dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal,” the Confederacy was an explicit rejection of that proposition. Alexander Hamilton Stephens, the vice president of the Confederate States of America, was exquisitely clear about this:

Our new government is founded upon exactly the opposite idea; its foundations are laid, its corner-stone rests, upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery—subordination to the superior race—is his natural and normal condition.

This has been the central quarrel in American history. A nation conceived in liberty and dedicated to human equality gave sanction to human bondage in its Constitution and laws.

This tension was played out in Fredrick Douglass’s brilliant and searing “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” delivered on July 5, 1852. Speaking to a largely white audience, Douglass insisted, “The Declaration of Independence is the ring-bolt to the chain of your nation’s destiny . . . . The principles contained in that instrument are saving principles. Stand by those principles, be true to them on all occasions, in all places, against all foes, and at whatever cost.”

But Douglass continued to his fellow citizens: “The rich inheritance of justice, liberty, prosperity and independence, bequeathed by your fathers, is shared by you, not by me.” To those enslaved and denied citizenship because they were black, the Fourth of July was “a day that reveals to him, more than all other days in the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim.” Douglass, speaking nine years before the Civil War, was following black Americans forgotten by history, who drew sustenance from the Declaration’s principles. Acting as citizens, a status they were all too often denied by law, they claimed the Declaration’s promise of equality, and asked their fellow Americans to recall the language of its creed: “all men are created equal.”

The 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments to the Constitution formally sanctified the principles of the Declaration. Taken together, these “Civil War amendments” abolished slavery, made all persons born in the United States citizens regardless of race, commanded the equal protection of the laws, and secured the vote for citizens regardless of race. The amendments promised a new birth of freedom. And for a fleeting moment, America experienced this rebirth with black Americans elected to the Senate and House of Representatives. But this promise was short-lived; it gave way to racial apartheid wherein white supremacy was written into American law.

Black Americans would have to wait another century to be genuinely included within the terms of American democracy, with the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Just at the Civil War amendments were in part inspired by the way in which Douglass and Lincoln drew on the principles of the Declaration, the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act were inspired by the civil rights movement as exemplified by Martin Luther King Jr.’s continued appeal to the principles of the Declaration to spur a nation to live up to its creed.

Those laws were passed over a half-century ago.

The struggle for America persists.

The brilliance of the American idea animates Lin-Manuel Miranda’s musical Hamilton, which first came to Broadway in 2015 and has premiered as a movie this weekend. The musical not only teaches Americans about their history, it properly claims that history for immigrants and citizens of color. Even more brilliantly, it embodies the idea of America by casting George Washington and company with actors of color. Miranda has Angelica Schuyler, Alexander Hamilton’s sister-in-law, sing a line from the Declaration—“We hold these truths to be self-evident / That all men are created equal.” She later riffs about getting Thomas Jefferson to “include women in the sequel.” It is an imagined America, but one made real by this son of immigrants. The show became an enduring success, with more than a million sales of its soundtrack and hundreds of thousands of schoolchildren taken to see it for free.

Yet alongside a few such cultural highs, there is the persistent reality of racial inequality. The ugly and brutal murder of George Floyd by officers of the state. Countless other black Americans brutalized by those who represent the law.

This is the sense in which President Trump has embraced the idea of the Confederacy. He defends monuments to Confederate “heroes” who took up arms against the United States in order to preserve a political order that continued the enslavement of blacks. Perhaps Robert E. Lee was, as his defenders say, just acting out of loyalty to Virginia. But in doing so, he cast his lot with the defenders of slavery and took up arms against his country. If it hadn’t been for President’s Lincoln’s leniency in order to “bind the nations wounds,” Lee would have been tried for treason. He was certainly treasonous to the idea of America.

From today’s vantage, it is astounding that America in the 1920s—which is when many of these Confederate monuments were erected—wanted to honor these individuals and their acts as part of a vast project of “redeeming the South.” The effort included smearing the promise of Reconstruction and the idea of equal citizenship for black Americans. It’s appalling that any American would want to honor these acts in 2020.

At the infamous “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville in 2017—the original purpose of which, overshadowed by the mayhem and death, was preserving a monument to Lee there—many of those marching chanted “blood and soil” and “you will not replace us.” Such language is unmistakable. It is an ethnic nationalist vision of America as a white man’s republic.

Yet Trump has made clear his sympathy for this understanding, presiding over a Republican party that is becoming increasingly—almost exclusively—white and Christian. Ethnic nationalism is resurgent in swaths of the Republican party and in conservative intellectual circles. Indeed, as Anne Applebaum has shown in the Atlantic, leading U.S. “national conservatives” have expressed admiration for Hungary’s prime minister, Viktor Orbán—a man famous for advocating “illiberal democracy,” with citizenship defined in ethnic and religious terms. Taking Orbán as a model sends an unmistakable message. To endorse this vision of ethnic nationalism is to betray the American idea.

We can take pride in the idea of America: a racially, religiously, and ethnically diverse republic bound by a set of common ideas is an extraordinary historical achievement. Yet more than two centuries into the American experiment, we must be humble in recognizing how far we have to go. The struggle before us, a struggle inextricable from the whole of our history, is to make that idea real—especially when it comes to race.

The poet Langston Hughes has given us the most sublime expression of this struggle in “Let America Be America Again.” He evokes some of what is best about America: pioneer dreams and liberty “where never kings connive nor tyrants scheme” and where “Equality is in the air we breathe.” But from the margins, those denied the promise mumble in the dark: “America never was America to me.” It is the hard truth of the unrealized idea. Yet driven by hard truths, the poem ends with a resounding commitment to the American idea that we can yet make our own:

O, yes, I say it plain, America never was America to me, And yet I swear this oath— America will be!