The Half Loaf

The Supreme Court decision in June Medical Services LLC v. Russo will give both sides of the abortion debate a little of what they want, and leave neither of them happy.

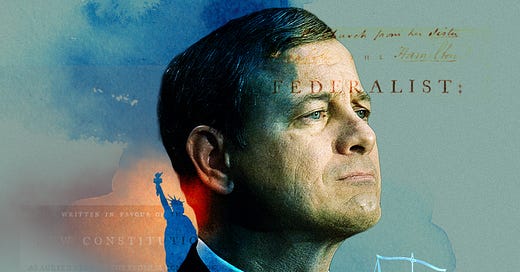

On Monday, in a 5-4 ruling, Chief Justice Roberts sided with the progressive wing of the Supreme Court in June Medical Services LLC v. Russo. The case struck down as unconstitutional a Louisiana law that would have required doctors to have admitting privileges at a hospital within a 30-mile radius of a clinic in which they intended to perform an abortion. Four years ago, on a 5-3 vote, the Court struck down a similar Texas law, with now-retired Justice Kennedy in the “swing” position.

The decision was the latest blow to social conservatives who, as recently as a few weeks ago, believed that they had the votes to enact their policy preferences at the SCOTUS level—only to find that conservative legal theory is less politically reliable than they had hoped.

But the big take-away from June Medical is that there were people on both sides of the political spectrum who expected that Brett Kavanaugh’s installation on the High Court was the death knell for the constitutional right to abortion. And both sides were wrong.

In his concurring opinion, the Chief Justice took pains to make clear that the question whether to retain Roe’s recognition of the abortion right itself—and, more specifically, the test for abortion restrictions established by Planned Parenthood v. Casey—was not present in June Medical. And he reminded the world that he dissented in the Texas case, believing it was “wrongly decided”—albeit on technical legal grounds.

These contradictory signals will no doubt be seized upon by both anti- and pro-abortion activists. That’s because both groups have an institutional stake in propagating the idea that the status quo ante on abortion is just about to change. And that the next case could be the one that alters the abortion landscape for forever.

Of course, just because activists have a self-interested reason to suggest this doesn’t mean they’re wrong. But to understand why both sides may well be wrong here, it’s worth examining how Chief Justice Roberts and Justice Kavanaugh, in particular, justified their votes in June Medical.

Roberts focused his opinion almost exclusively on stare decisis principles—the idea that courts should “stand by things decided” and give “fidelity to precedent.” Adherence to precedent, Roberts explained, “is necessary to avoid an arbitrary discretion in the courts”—which is precisely the type of limitation on judicial power that conservative “originalists” self-righteously tout. It’s also “grounded in a basic humility that recognizes today’s legal issues are often not so different from the questions of yesterday and that we are not the first ones to try to answer them.”

Were this Court to again face the question decided by Roe in 1973—whether the Constitution protects women from government interference in abortion as a matter of substantive due process—Roberts could well apply the same logic to justify leaving Roe and the numerous cases that applied it alone. It would be strange for Roberts to make a show of the beauty of stare decisis in this case only to ignore it in the next.

More to the point, no Supreme Court is eager to rule in favor of abortion opponents unless and until public opinion has turned wildly in their favor. Roberts acknowledges this with his caveat that precedent may be disturbed if “subsequent factual and legal developments” call for it. Which suggests that so long as he remains the swing vote, Roberts will preside over the reversal of Roe only if it means ratifying a sea-change in public opinion.

As for the anticipated white knight for the anti-abortion minority, Justice Kavanaugh did deliver on a dissent. But he did so on the rationale that doctors were not the proper plaintiffs to bring the case. He also wrote separately to explain that he wanted to see a fuller factual record on whether doctors who perform abortions would have a hard time getting admitting privileges in Louisiana. Kavanaugh did not say that he would have taken this case as an opportunity to overturn Roe itself.

To the extent Kavanaugh took issue with the constitutional test for abortion restrictions, he rejected the use of a balancing test for abortion rights—that is, one that weighs the interests of the woman against the interests of the state. All told, therefore, June Medical Services reaffirms the basic test in Casey: That so long as a state has a legitimate purpose to impose a restriction on abortion that’s reasonably related to its goal, the law is constitutional unless it has the “effect of placing a substantial obstacle in the path of a woman seeking an abortion of a nonviable fetus.”

The key word here, of course, is “substantial” (or in other parlance, “undue”). This standard is not clear-cut, which means that legislators may continue to curtail abortion through legislative impositions of abortion restrictions on the theory that the burden imposed on women is not “substantial” or “undue.”

Which is a perfect recipe to leave both pro-choicers and pro-lifers upset. Abortion rights advocates will see courts allow certain restrictions to abortion that they find intolerable. And pro-lifers will see that even though a conservative-leaning Court on balance upholds more restrictions than a progressive-leaning Court would, the fundamental framework of Roe will not be overturned.

Both sides will get a little of what they want and neither will be happy.