The Internet of (Demonic) Things

Online life’s ambient hostility, the dangers of kayfabe, and why it’s becoming more important to keep part of yourself in reserve.

When the subject of the internet arises, I like to use a line that contrasts it with another part of our inheritance from the national security state: “The most dangerous invention of the twentieth century was not the atom bomb, but the internet.”

I’m not serious, but I’m also not joking. I suspect I mean it in the same way that Sam Kriss means it when he writes, “the internet is made of demons.” (Hat tip to Jonathan V. Last for recently highlighting this piece in his Bulwark newsletter.)

“This theory is—probably—a joke,” writes Kriss. “It is not a serious analysis.”

“But still,” he goes on, “there’s something there.”

There are ways in which the internet really does seem to work like a possessing demon. We tend to think that the internet is a communications network we use to speak to one another—but in a sense, we’re not doing anything of the sort. Instead, we are the ones being spoken through. Teens on TikTok all talk in the exact same tone, identical singsong smugness. Millennials on Twitter use the same shrinking vocabulary. My guy! Having a normal one! Even when you actually meet them in the sunlit world, they’ll say valid or based, or say y’all despite being British. Memes on Instagram have started addressing people as my brother in Christ, so now people are saying that too. Clearly, that name has lost its power to scatter demons.

There is something unsettlingly apt about the metaphor: Spending large amounts of time on social media can indeed seem like a possession by something outside us. Traditional theology gives one picture of this state, but a secular version might figure it in an addiction like alcoholism. (Think, for example, of the expression “demon rum.”) Like these states, protracted internet dependence warps your perception of people. It wears down your attention span, makes you irritable, and fractures your day into dozens or hundreds of unconnected bits and pieces. It invites you to create your own world: With the click of the block button, I can make people I don’t like disappear. By adding “passed away” to my muted phrases list, death begins to vanish. I can mute a handful of carefully chosen terms to silence virtually any contentious debate. Twitter is not real life; in what Kriss calls the “sunlit world,” this kind of curation is far easier imagined than achieved.

There’s also an uncanniness in seeing all sorts of jumbled thoughts mixed together, with the most disturbing ones exerting an almost irresistible, voyeuristic pull. Sometimes there’s a feeling that something—some force? some consciousness?—is pressing into your skull, sinking its—tentacles? fingernails?—into your brain. It feels as though some important barrier is being penetrated, some inner sanctum being breached.

My reaction to Kriss’s joking-not-joking equation of the internet with demonic possession struck me because I have been thinking about social media in a similar way for some time, and have been trying to back away from using it for that reason. I know I’ve been online too much when my mind responds to some innocuous real-world remark with a meme or a reference to some outrage that very few people outside of Twitter will recognize—or when I am tempted to make an important real-world decision on the basis of reactions I received to a comment online.

I suspect all of this is quite common among people like me—people whose work takes place mostly in our own heads. With all the talk about a labor shortage, I’ve occasionally half-considered working in a store or supermarket: Wages would be low and retail work is notoriously stressful, but at least I’d have my mind to myself.

For me, the real takeaway from Kriss’s internet demonology is the necessity of keeping pure that inner sanctum. You notice in people you respect a sort of adult seriousness, which comes from a part of ourselves where nothing intrudes but God, family, and self: That’s the sanctum. Perhaps it’s a bit like a piece of advice Korean-American singer and author Michelle Zauner attributes to her mother in her memoir, Crying in H-Mart: “Some of the earliest memories I can recall are of my mother instructing me to always ‘save ten percent of yourself,’” Zauner writes. “What she meant was that, no matter how much you thought you loved someone, or thought they loved you, you never gave all of yourself. Save 10 percent, always, so there was something to fall back on.”

It’s a distinct point all its own, but it also dovetails with the confusion of self that can follow when you become a character or a personality. The problem with being performative on the internet—of having a “brand”—is that you may come to allow all sorts of ephemeral garbage to penetrate that inner sanctum, and eventually it may cease to exist. (Maybe, for example, you write about how getting sick is noble and virtuous because there are dastardly liberals out there who don’t want to get sick. I wish I were making that article up, but I’m not.)

More generally, the volatile combination of the pandemic and the internet has distorted a lot of our thinking and even compromised our ability to converse with each other. But the pandemic’s inflection of the internet has only underscored what was already there. The stakes have been raised, but the game hasn’t changed.

Speaking of becoming a character, it’s often said of professional wrestling—more so in the bygone era of kayfabe—that wrestlers sometimes lost their sense of self because the line between them and their characters broke down. That destruction of the person may have been a side effect, or it may have been a desired objective of their act; in some cases, real events and fabricated ones became intertwined. A real-life divorce, for example, could turn into just another piece of material for the storyline. (This brief article gives a taste of how seriously wrestlers from this era took their performance.)

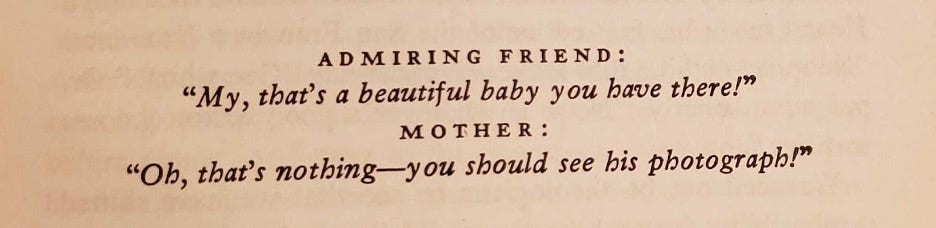

Along similar lines, Daniel Boorstin opened his 1962 classic The Image with a joke about the blurring of the lines between reality and reproductions of reality:

But we were talking about demons.

Of course, casually comparing Twitter to Satan based on an article you saw quoted in a Substack newsletter is a perfectly typical example of being “too online.” The usual conservative/libertarian answer to the challenge of the demonic internet would be to simply advise users to get off Twitter. But this individualizes a social problem and thereby attempts to define it out of existence. That is insufficient because it theoretically entails that there are no real social problems at all—and therefore no need for policy or politics.

Made of demons or not made of demons, the internet, and social media in particular, are phenomena we increasingly understand to have real human costs. “Depression in girls linked to higher use of social media,” reads a 2019 Guardian headline. “The preponderance of the evidence suggests that social media is causing real damage to adolescents,” reads the subtitle of a 2021 Atlantic article.

I think about a lot of people my age—their snarky, jaded style, their dark sense of humor. Some of that might simply be a result of growing up with Jon Stewart, but I wonder how much of it could be rooted in a premature exposure to things they shouldn’t have seen. Everyone my age knows that feeling of fear and adrenaline that comes from purposely or accidentally seeing something on a screen that you know you shouldn’t have, especially when it happens in the darkness of the middle of the night while your parents sleep. Maybe, over and over, such exposures do something to you. Perhaps the violence, the smut, the disturbing stories of death and crime and addiction and depression and grief mixed in with lighthearted comments—perhaps this mix of terrible and trivial things lodges itself into your psyche and continues to accumulate there, the emotional equivalent of persistent organic pollutants. Perhaps one day we will understand the act of giving a child a laptop or smartphone before her brain is close to fully formed the same way we understand candy cigarettes today.

There are some things we do not try to use safely or responsibly because we understand it would be difficult or impossible to do so. Social media—let alone the whole totality of the internet—probably isn’t quite one of those things. But the jury may still be out. And even if we end up judging it more moderately—as more akin to alcohol than fentanyl—some people will still be unable, for whatever reason, to partake of the potable river of online life in moderation. We should always be humble about what we don’t know, after all. In a very different world not so long ago, more doctors smoked Camels than any other brand.