The Last Authoritarian World Cup

The World Cup and the Olympic Games are too important to the common life of the world to be surrendered to rich autocracies.

In 1986, the International Olympic Committee voted to split the Winter and Summer Olympics so they would alternate every two years instead of occurring together every four years. The new tradition began in 1994 with the Lillehammer Winter Olympics, site of the infamous showdown between figure skaters Nancy Kerrigan and Tonya Harding. The IOC initiated the split schedule in part to bring greater attention to the winter events, and while this move did bring them out from the shadow of the more popular summer games, it also locked the Winter Olympics into permanent competition with an even bigger quadrennial athletic spectacle: the World Cup.

Since 1994, the two mega-events have occurred in the same calendar year, with the Winter Olympics kicking things off in the early months and the World Cup picking things up around the midway point. Both have become notorious as money-losing debacles rife with graft and corruption, bringing chaos and misfortune to their host cities—but until recently, the prospect of hosting the Cup or the Olympics continued to present an irresistible showcase opportunity to Western-style democracies. That’s changed drastically over the past decade: Local taxpayers are increasingly uninterested in holding the bag for a month-long party for tourists. FIFA and the IOC have been forced to look elsewhere for willing hosts, and the most willing of all have turned out to be the world’s rich autocracies.

These autocracies have made quite the pitch, offering an open checkbook, an eagerness to expand their surveillance states, and a willingness to ignore any environmental concerns to make sure the games go off smoothly. What better way to bolster your global image as a modern and forward-thinking nation than by welcoming the entire world to your backyard for some good old-fashioned sportswashing?

In 2014, Russia put on the winter games in Sochi, a Black Sea resort village famous for being one of Stalin’s favorite vacation spots. While Russian President Vladimir Putin was denied the glory of seeing Russia win hockey gold on home soil—they were eliminated singlehandedly by American T.J. Oshie in the knockout round—Putin was still provided a major global propaganda win simply by hosting. Less than a week after the close of the Sochi games, Russian forces launched their operation to seize Crimea. That didn’t stop IOC President Thomas Bach from praising Russia as a host the following year.

Four short years after the Sochi games, and following a host-selection process marred by allegations of rampant corruption, FIFA decided it had to stick with Russia as the host for the 2018 World Cup, even though Russia was poisoning British diplomats and maintaining military units across Crimea. The Cup gave Putin another opportunity to present his carefully curated vision of Russia to the international community. How did the world’s most powerful athletic governing body respond? FIFA President Gianni Infantino called it the best World Cup ever. “Everyone has discovered a beautiful country, a welcoming country, full of people who are keen to show to the world that what maybe is sometimes said is not what happens here,” he said.

After Oslo, Stockholm, Lviv, and Krakow withdrew their bids to host the 2022 Winter Olympics because they lacked local support, the IOC found its choices limited to Beijing and Almaty, Kazakhstan; the IOC selected Beijing. Eager to duplicate the dazzling success of the city’s 2008 Summer Olympics, the Chinese reused many of the facilities from those games and promised to overcome any weather issues, environmental consequences be damned. Beijing would make history as the first city to host both the winter and summer games, earning the Chinese Communist Party another propaganda victory. Or so they thought.

The ongoing pandemic—and President Xi Jinping’s draconian “Zero-COVID” policy in response to it—decimated the games’ potential as a global tourism event. China’s alleged genocide of Uyghurs in Xinjiang precipitated boycotts—the United States did not send an official delegation to this year’s games, although American athletes competed individually—and led many to simply tune out entirely, making this year’s games the least-watched (by Americans) Olympics ever. For those who did tune in, the most memorable image to come from the Beijing winter games was a snowboard competition held against the dystopian backdrop of the cooling towers of a derelict steel plant.

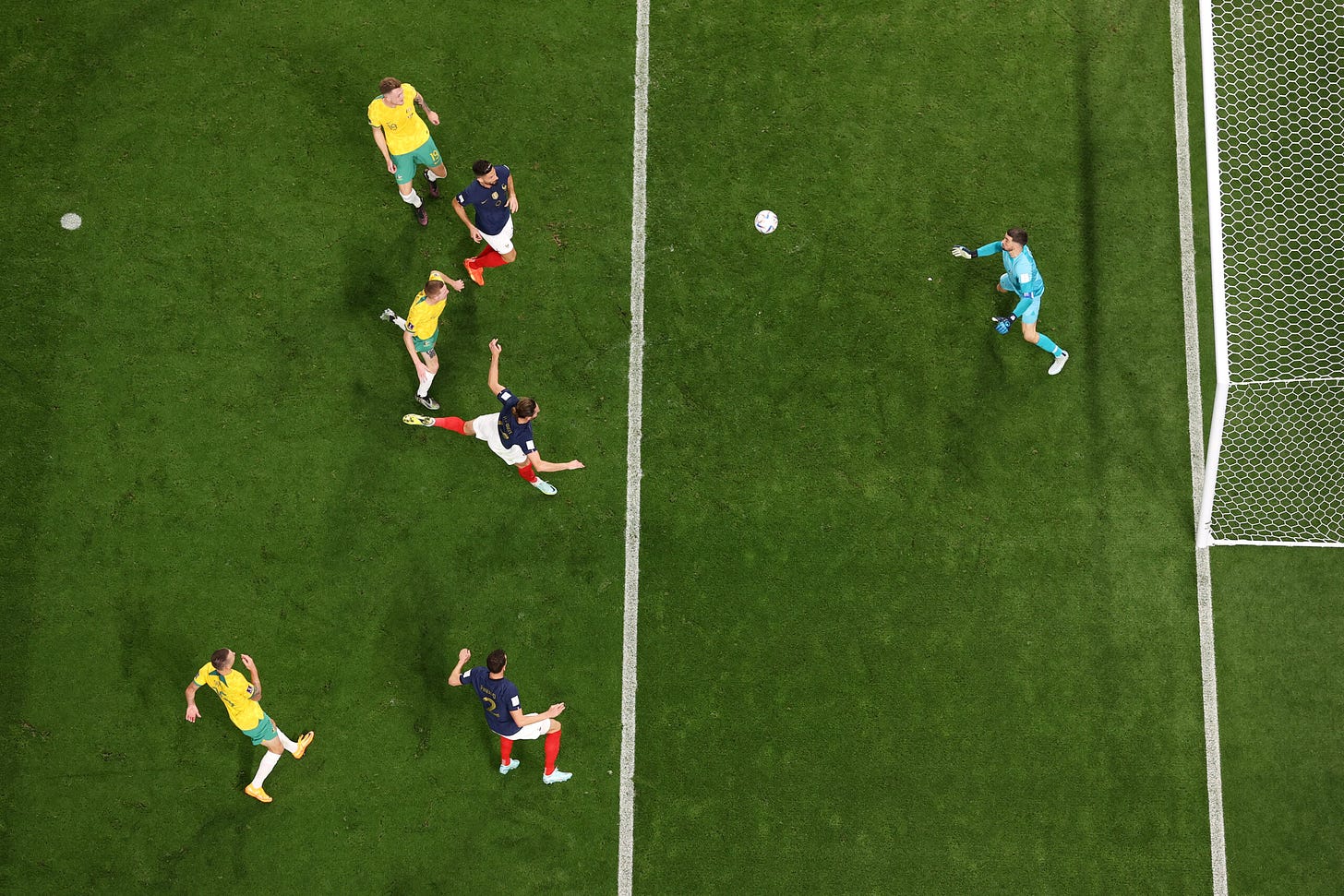

All this brings us to Qatar, host of the 2022 World Cup. Allegations of bribery and corruption have followed the Qatari bid from the moment they were announced as hosts. A sweeping Department of Justice investigation into the bidding process led to the 2015 indictments of nine high ranking FIFA officials. It’s virtually impossible to avoid assuming malfeasance: How else would so many FIFA officials come to choose a country the size of Connecticut with no soccer history or suitable civic infrastructure to host the world’s greatest sporting event? The country proposed to spend $220 billion building all-new, state-of-the-art facilities to secure its bid; the sum is a full order of magnitude above the next-most-expensive Cup, which Brazil managed to cover in 2014 for just $15 billion. Even with the enormous budget, Qatar has had to introduce some very ad-hoc seeming solutions: For instance, to handle the population influx in excess of what local hotels can accommodate, tents have been set up on the Doha outskirts and cruise ships have anchored in the harbor; airlines are also operating dozens of extra flights a day to ferry thousands of spectators to the tournament from lodgings in nearby Dubai. The country has also implemented novel outdoor cooling systems in its new stadiums to make spectators and players alike more comfortable. Qatar is in a desert, after all, which is why the World Cup moved the 2022 schedule to late fall. The country’s summers are just too oppressive for strenuous outdoor athletic activity. Unless, of course, you’re a migrant laborer.

Qatari government sources report that its population is just over three million, but migrant workers make up 85 percent of that figure, according to the New York Times. The country’s foreign labor force, drawn from across Central and Southeast Asia, works in dangerous conditions on terms that often border on indentured servitude. In 2021, the Guardian reported that over 6,500 migrant construction workers have died in Qatar since 2010, the year the country was awarded hosting duties for 2022. Qatar quibbled with the substance of the Guardian’s reporting, claiming that some of the deaths recorded in the Guardian’s figure were those of workers not assigned to World Cup projects, and otherwise declaring that “the mortality rate among these communities is within the expected range for the size and demographics of the population.”

Beyond its poor treatment of its population of migrant laborers, Qatar is also simply an odd setting for the World Cup’s legendary atmosphere. Want to crack open a cold one courtesy of Budweiser, an official FIFA sponsor? Well, good luck. Qatar’s strict interpretation of Sharia law makes drinking nearly impossible; alcohol sales were banned in World Cup stadiums just two days before the first match. And if you’re part of the LGBTQ community, don’t even think about showing it. When Qatar World Cup ambassador Khalid Salman was addressing the possibility of gay fans attending, he told German television broadcaster ZDF that homosexuality is forbidden in his country because “it is damage in the mind.” The interview was promptly halted by his minder. (Spectators have since reported being confronted and turned away from matches for wearing clothing with Pride colors.) Reporting on these developments hasn’t been easy, as Western media outlets have documented harassment from local Qatari officials for even the most basic reporting. If Qatar expects this World Cup to be a propaganda win for its de facto hereditary monarchy—members of the Al-Thani family have presided over the country since the nineteenth century—they are off to a very poor start.

The close of this year’s World Cup will mark the end of an eight-year run of authoritarian nations hosting the world’s biggest sporting events, which will thereafter return to hosts in Western-style democracies. The 2026 World Cup will be the first ever to be jointly hosted by three nations: the United States, Mexico, and Canada. (Matches will be held in 16 different cities, further relieving the financial and infrastructural burdens of hosting.) And last year, negative press and the recent drop-off in bids to host the Olympics finally moved the IOC to impose much-needed reforms, a recognition of the fact that it could either change or be reduced to a tool of propaganda for wealthy authoritarian states willing to host. Through 2032, the Olympic Games have been or will be awarded to countries that uphold and respect the ideals of peace, freedom, and democracy. It is even possible that the Winter Olympics will return to Salt Lake City in 2036.

Hosting rights for these events should be limited to Western-style democracies permanently. The Olympics and World Cup are simply too big and too important to the common life of the world to be surrendered to authoritarians bent on exploiting them. As the struggle between democracies and autocracies becomes the focus of twenty-first century geopolitics, it is imperative that Qatar’s 2022 tournament be the last authoritarian World Cup.