The New Workplace Gender Imbalance: Social Capital and Job Satisfaction

New data suggests gender and education are the difference between liking and loving your job. But there’s a price to be paid.

The U.S. labor market has been dramatically transformed over the past few decades. At the height of the manufacturing economy in the late 1970s, the assembly line with its routine, manual tasks provided ample, well-compensated jobs that were disproportionately held by men. Today’s post-industrial economy dominated by services and information, on the other hand, places a high (and growing) premium on “soft” skills—teamwork, communication, interpersonal skills, collaboration. In general, women have these skills in greater abundance—which is a major factor in why, in today’s “social workplace,” women are thriving and while men are falling behind.

In June, we asked over 5,000 Americans in a statistically balanced survey a range of questions about their jobs. Their responses, summarized in our new report, “The Social Workplace,” reveal a wealth of insights about how social capital and workplace connections influence work attitudes and job satisfaction and how women are benefiting from the shift toward a greater emphasis on human-facing skills.

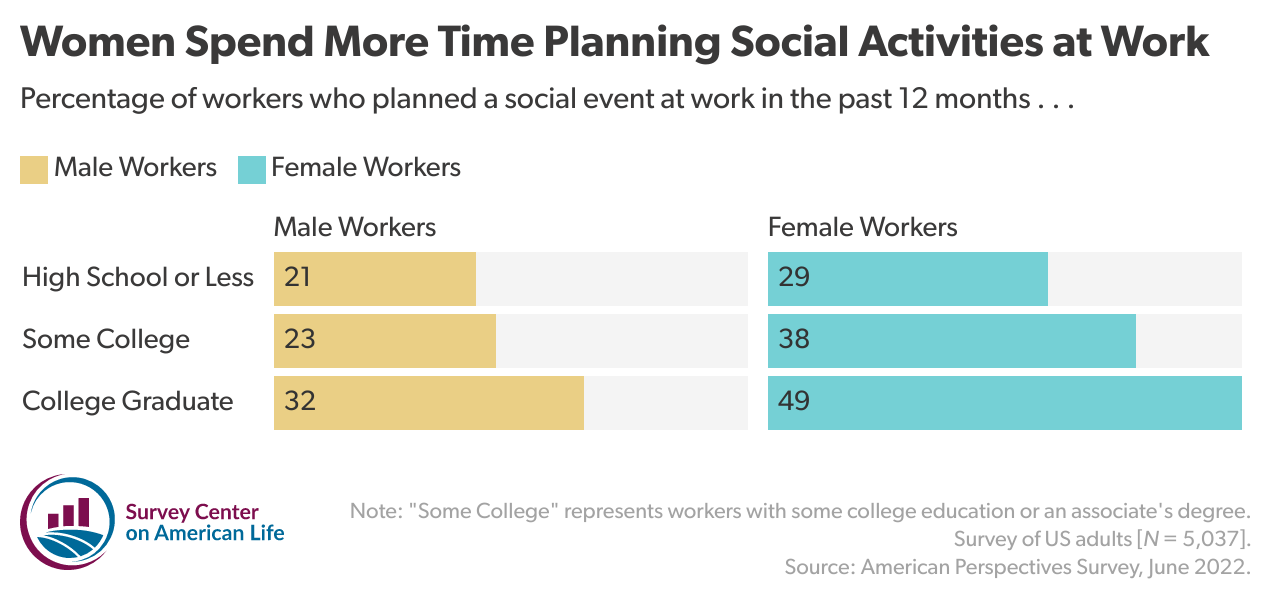

The workplace shift is part of a general trend in American society. From PTAs and churches to book clubs and charitable volunteering, women’s inclination and interest in creating social capital far outpaces men’s. Likewise, across industries and jobs, female workers are more socially invested than their male counterparts and serve as the prime movers in generating workplace social capital. While 42 percent of women reported helping to organize a social activity at work in the last 12 months, only 25 percent of men said the same.

Women, especially those who are college educated, also invest more in establishing and cultivating personal relationships on the job. More than 6 in 10 (62 percent) college-educated women said they discussed personal issues with coworkers in the previous month, compared to less than half (47 percent) of college-educated men. Just 35 percent of men with a high school education or less said they talked about personal issues with coworkers in the previous month.

Investment in workplace socializing pays off when it comes to work happiness. Workers who say they have “close” friends at work are far more likely to think positively about their jobs in terms of satisfaction, fulfillment, and experiencing a sense of excitement and engagement in their work. Workers who don’t make social investments—especially non-college-educated men—are much less likely to say the same about their jobs.

Socially invested women are also more likely to report feeling appreciated by their bosses (55 percent), especially compared to non-college-educated men (38 percent). This expressed appreciation makes a difference. Among those who said their boss shows appreciation, 70 percent said they were very or completely satisfied with their jobs, compared to 27 percent among those who said their boss never shows appreciation. Work satisfaction is a cycle: social investment and enjoyment are mutually reinforcing.

If the social workplace offers considerable benefits to workers, it also imposes costs.

Among those more socially active at work (again, mostly women), 63 percent reported feeling “anxious or worried” and/or “stressed out or overwhelmed” at work. Eighty-one percent of college-educated women report being stressed out at work in the last week compared to 71 percent of college-educated men, 74 percent of high-school-educated women, and 65 percent of high-school-educated men. Women and men with high levels of education and job satisfaction tend to be more preoccupied with work and say they think about their jobs even when they aren’t working. These workers are three times as likely to say they feel anxious every day compared to less educated workers. This trend, colloquially known as “workism,” is most pronounced for those with graduate-level education. When it comes to career satisfaction, there’s no free lunch, psychologically or otherwise.

Workism isn’t the only thing producing anxiety and stress in the workplace. College-educated women tend to experience higher levels of professional doubt (aka “impostor syndrome”), with 39 percent of college-educated women doubting their professional abilities and achievements. To complicate workplace social dynamics further, women continue to experience informal discrimination on the job. About one in ten women surveyed said that in the previous month they heard a sexist joke in their workplace, which is associated with negative impacts on overall workplace satisfaction.

That college-educated women are socially engaged in the workplace, and enjoying the benefits of this labor, is a cause for celebration, after decades of struggling against discrimination, harassment, or worse. At the same time, we need to recognize that men, and especially those without college degrees, are falling further and further behind the social curve. This isn’t a trivial matter: Social capital matters in finding, keeping, and advancing in jobs. As Brookings Institution scholar Richard Reeves argues, what is needed are new strategies and approaches that enable men to drop stereotypes about what constitutes “men’s” work and equip them with the skills they need to enjoy the fruits of a dynamic and growing economy.