The Prescient Literary Visions of Vladimir Voinovich

The Russian satirist lampooned everything from the toxic apathy of his compatriots to Putin himself, but he never lost hope.

Vladimir Voinovich, one of the great Russian writers—and great dissidents—of his time, would have turned 90 on September 26. Had Voinovich, who died of heart failure at 85 in July 2018, lived to see this day, it would have been a bittersweet birthday. A man passionately devoted to freedom, intensely sympathetic to the liberation of Ukraine (to which he had strong personal ties), and warily hopeful about a democratic revival in Russia, Voinovich would have been devastated by Vladimir Putin’s war on Ukraine. As a writer with a keen satirical vision—often, especially in his later years, a surreal and dystopian one—he might also have felt vindicated by current events, in the worst possible way. But he might also have observed that current events have topped his most over-the-top dystopian fantasy.

Voinovich’s anniversary is, in a way, a bittersweet date for me as well: As I chronicled in a Weekly Standard article on his life and death, I was privileged to share an all-too-brief friendship with the novelist in his final years after many decades as a fan. We nearly had a creative collaboration—in 2016, Voinovich asked me to translate the novel that turned out to be his last, The Crimson Pelican, into English—which didn’t happen because a publisher got cold feet and other publishers thought the book wasn’t marketable enough. A pity for many reasons: not only because Voinovich, while by no means a vain man, was palpably chagrined by the dimming of his star on the Western literary stage after earlier successes, but also because the novel, a savage satire of Putin’s Russia, would have been more relevant than ever right now.

Born in then-Soviet Tajikistan in 1932, Voinovich had an extraordinary life that spanned Joseph Stalin’s Great Terror and World War II (his own father Nikolai, a newspaper editor, survived both: arrested in 1936, he was sent to the gulag but released several years later to join the Soviet army after the German invasion, and came home disabled but alive); Nikita Khrushchev’s “thaw,” under which the young Voinovich launched a successful literary career; Leonid Brezhnev’s Big Chill, which turned him into a blacklisted dissident and ultimately got him banished from the USSR; Mikhail Gorbachev’s glasnost and perestroika, which allowed him a triumphant return; the collapse of the USSR; and then the rise of Putin’s neo-autocracy, which reduced him to the status of what he wryly called “persona half grata.”

Along the way, there were triumphs: Voinovich’s 1969 masterpiece, The Life and Extraordinary Adventures of Private Ivan Chonkin, blocked from publication in the Soviet Union and published in the West, made him internationally famous and was eventually translated into some 40 languages. There were tragedies, too. Irina, Voinovich’s beloved wife of 40 years, lost an arduous battle with cancer in 2004. He also outlived both his children from a brief first marriage: Daughter Marina died from an overdose of alcohol and prescription drugs in 2006 at the age of 48; son Pavel suffered a fatal heart attack in March 2018 at the age of 55. (His only child with Irina, Olga Voinovich—herself a writer—lives in Germany, where she was born during her father’s exile; he was also survived by his third wife, Svetlana Kolesnichenko, a previously widowed businesswoman with whom he had bonded through shared bereavement.)

Throughout it all, some things never changed: Voinovich’s insistence on truth-telling (one of his early short stories, published in the Soviet magazine Novy Mir in 1963, was titled “I Want to Be Honest”); the sharpness of his mind, undiminished when he was already in his eighties; and the sense of humanity that never left him even when he wrote savage satire. All three qualities shine in Private Ivan Chonkin and in its two sequels, Pretender to the Throne (1980) and A Displaced Person (2007).

The hero of this tale, which begins on the eve of the German invasion of the Soviet Union, is a simple-minded, good-hearted Soviet recruit who wants nothing more than to complete his service and marry the young woman he meets in a village where he is assigned to guard a small aircraft left behind after an emergency landing. But fate wills otherwise: The hapless Chonkin is arrested as a deserter after a series of misunderstandings and misadventures, then declared an enemy of the people when local officers of Stalin’s secret police, the NKVD, select him as the victim for a big show trial in their provincial town. (He is also proclaimed to be an émigré aristocrat sent back to the Soviet Union as a subversive.) Saved from execution when the town’s Soviet authorities flee from advancing German troops, Chonkin flees into the woods and ends up in a Soviet partisan group and, eventually, back in the army—until some more crazy but just-about-plausible hijinks of fate bring him to postwar America for a fresh start as a farm laborer. The end of the third novel sees “John Chonkin,” a prosperous widowed farmer, visiting Moscow as part of an American delegation in the Gorbachev era—and having a wistful, too-late reunion with his old village girlfriend and only true love, Nyura.

The Chonkin novels ruthlessly skewer the inanities and insanities of Stalin’s USSR, where a careless remark can spell one’s doom and even the powerful cower in fear of making a fatal misstep (or of being denounced by someone with a grudge). Especially vigilant citizens write to the NKVD about coded anti-Soviet words in popular song lyrics. A collective farm chairman can get in trouble for harvesting crops based on the weather rather than instructions from the local Communist Party committee. A small-time party minion is ordered to gather villagers for a “spontaneous rally” in response to the German invasion—but when he reports that they have already gathered in front of the village council after hearing the news, it turns out that an unauthorized rally is a little too spontaneous. (The assembled villagers are dispersed, then herded back into the square ten minutes later.) NKVD agents are so used to manufacturing fake cases that when they have to catch an actual German spy that radio intercepts show is operating in the area, they have no idea how to go about it.

Next to the Chonkin trilogy, Voinovich’s best-known work is probably Moscow 2042 (1986), a satirical dystopia that earned him the reputation of a prophet. Traveling forward in time, the narrator finds a post-Soviet dictatorship that represents a symbiosis of a KGB-controlled state and the Russian Orthodox Church; by the 2010s, this seemed uncannily predictive of the Putin regime. Voinovich always denied his prophetic gift, arguing that he was merely extrapolating from contemporary trends: the KGB’s growing power and the church’s growing popularity. Yet there’s also the even more uncannily coincidental fact that the supreme ruler of Voinovich’s fictional state is, like Putin, a former KGB officer once stationed in Germany.

The cover of Voinovich's last book, The Crimson Pelican.

In a 2014 appearance in New York, not long after the “Revolution of Dignity” in Ukraine and the Russian annexation of Crimea, Voinovich only half-jokingly told the audience that if Russia did not change its course, he would have to “write another book: Moscow 2092.” What he was actually writing at the time was The Crimson Pelican, in which the absurdities of Putin’s Russia are given a fittingly surreal treatment. The narrator, elderly writer Pyotr Smorodin (clearly a Voinovich alter ego), is bitten by a tick in the woods near his country house outside Moscow and gets an ambulance to take him to a city clinic. The ambulance ride becomes a never-ending journey in which dreams, delirious visions, and reality merge and overlap. The annexation of Crimea turns into a dream in which Russia has annexed Greenland, jubilant crowds chant “Green is ours,” and Kremlin propagandists on TV are busy proving that Greenland is an ancient Russian land. (Here, Voinovich’s prophetic powers were just a bit off: It was not Putin but his on-and-off pal Donald Trump who made noises about buying Greenland.) The motorcade of the Supreme Leader, i.e. Putin, holds up traffic for fantastically endless hours; when a woman in labor dies during the wait, Zinulya, the patriotic paramedic taking Smorodin to the clinic, sobs imprecations blaming her death on Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton, then the twin monsters of Putin’s propaganda.

Toward the end of the novel, Smorodin not only meets the leader—here known by the moniker Perligos, a deliberately ludicrous abbreviation for “First Person of the State”—but gets a surprise offer to succeed him as head of state. Apparently, the only thing Perligos really wants is to retire with a modest nest egg of two—no, make that four—billion dollars and thereafter devote himself to caring for a rare breed of almost-extinct pelicans (a swipe at Putin’s much-ballyhooed 2012 stunt of leading a flock of rare cranes on the first leg of their annual migration route in a motorized hang glider).

What Smorodin wants, meanwhile, is to foment a revolution that will allow Russians to win their own freedom and assert their own rights. The best way, he decides, is to undertake so outrageous and senseless an assault on their dignity that even the most passive will rise up. After hearing about a (real-life) police brutality case in which the victim was sodomized with the shaft of a spade, Smorodin gets what he thinks is a brilliant idea: an announcement that every adult Russian must report to a designated station to undergo such a procedure for character-building. But the scheme backfires: a massive, raucous crowd that Smorodin initially mistakes for a protest turns out to be a government-authorized demonstration with slogans like “Let’s take a shaft to NATO’s futile hopes!” and “Support universal shafting.” At that point, Smorodin wakes up to realize that the ambulance is finally at the clinic and his stint as subversive-in-chief was a dream . . . or was it? A strange twist at the very end suggests at least some ambiguity.

The Crimson Pelican has a wide range of political and philosophical themes, including a critique of the cult of macho: Told by Zinulya that “a real man is born a warrior,” Smorodin retorts that a man is “a human being who thinks and feels, who has as much right as a woman to fear death, pain or humiliation”—and who should be raised to feel revulsion at the thought of killing or hurting others, except in the most extreme circumstances. But the novel also has a prominent ”Ukrainian theme,” with Moscow and Kyiv sometimes merged in Smorodin’s hallucinatory visions. “The country next door” is invoked as both a contrast and a model: Russia, where the population spends its spare time “drinking vodka and staring into the TV box,” is juxtaposed against Ukraine, where the people come out to topple an oppressive ruler. “They’re crazy over there,” Smorodin says, with bitter sarcasm, to an American official who is also interested in a Russian revolution. “One person gets killed, and they all get upset as one people.”

Voinovich’s interviews in Ukrainian media in the final years of his life reveal that the subject of Ukraine was near and dear to his heart—both because he saw Ukraine as a model for Russia in real life, and because he had a very real attachment to Ukraine and its culture. Both his parents were born in Ukraine; three of his grandparents, he told the Ukrinform website in September 2016, were from Odessa. Voinovich himself lived in the Zaporizhzhia region (then known as Zaporozhye) for most of his adolescence, between the ages of 13 and 19, and spent most of his army service stationed in Ukraine—including the Luhansk and Kharkiv regions, where Russian soldiers have been battling Ukrainian soldiers in recent weeks. The same interview reveals that he was not only fluent in Ukrainian (though “not as fluent as I used to be,” he told the journalist) but preferred to read foreign literature in Ukrainian rather than Russian translation if available. As a young man, Voinovich said, he never thought of Ukraine and Russia as different countries: They were simply part of the USSR, like other Soviet Republics. But he was well aware of a distinct Ukrainian culture—not only literature but songs, folk tales, and humor, “all strongly different from Russian ones—you can’t fail to feel it.” By the time Gorbachev-era change began to rock the Soviet Union, Voinovich said, “it was obvious” that Ukraine aspired to nationhood and sovereignty; by 1990, he has no doubt that Ukraine would want “maximum, complete independence.”

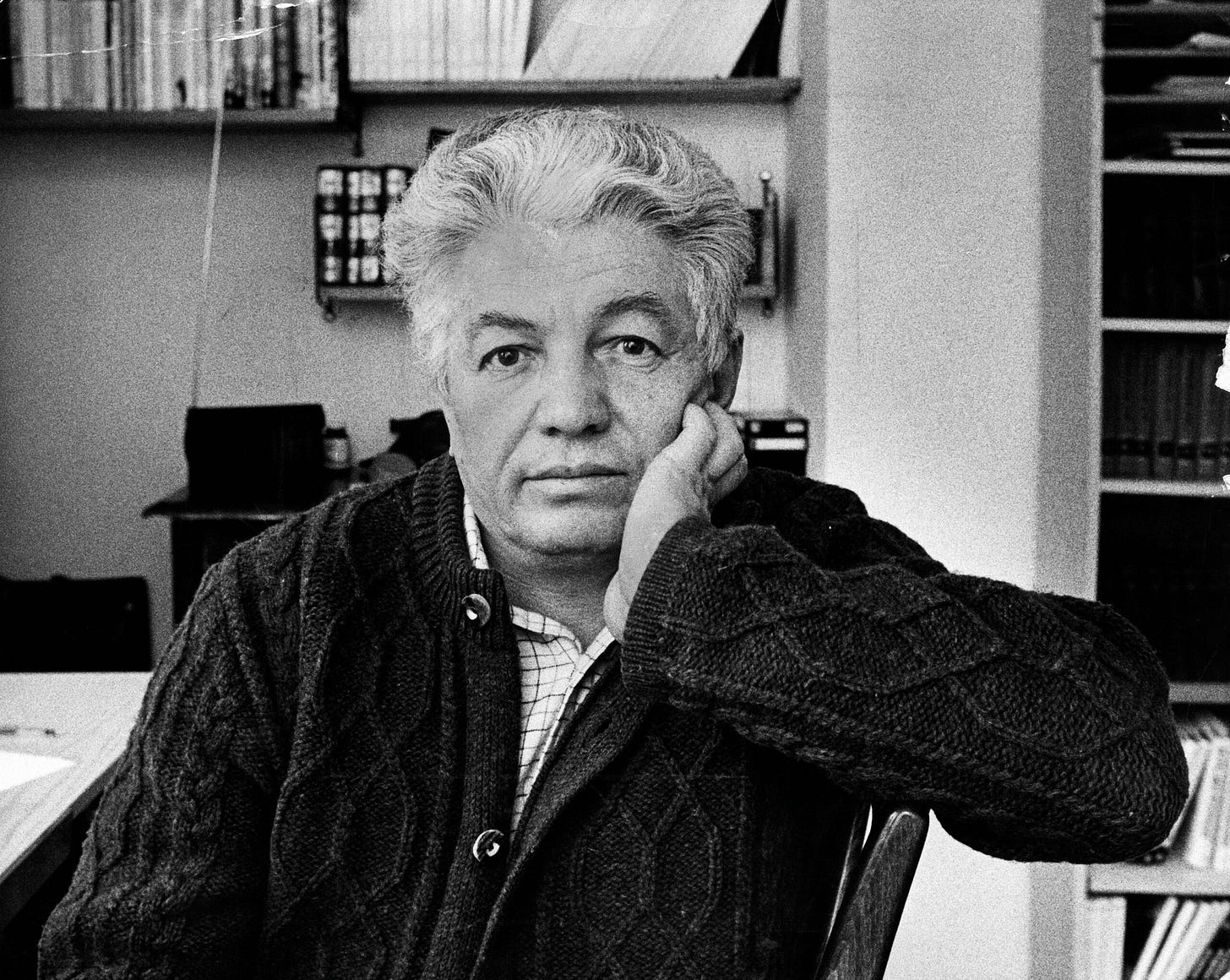

Voinovich in January 2017. Photo courtesy of Cathy Young.

In the same interview, Voinovich made it clear that his sympathy in the conflict between Russia and Ukraine was entirely on Ukraine’s side and that he saw the “separatist insurgencies” of Donetsk and Luhansk as Putin’s war intended to destabilize Ukraine’s fledgling democracy: “He cannot allow successful development in Ukraine—the example would be too tempting for Russia.” Voinovich was also an outspoken advocate for Ukrainians held in detention in Russia, such as fighter pilot and prisoner of war Nadezhda Savchenko—given a 22-year sentence by a Russian court for allegedly killing two Russian journalists in Ukraine but pardoned by Putin in May 2016—and filmmaker Oleg Sentsov, seized by Russians in Crimea in 2014 and sentenced to 20 years on bogus charges of terrorism. Despite his frail health in the final months of his life—he was shattered by the unexpected news of his son’s death—Voinovich continued actively campaigning for Sentsov’s release, which he did not live to see. (Sentsov was freed in 2019.)

Some six months before he died, talking to Ukrainian journalist Dmitry Gordon, Voinovich was scathingly critical of Putin’s war but also cautiously optimistic in the long term:

I think this is madness, and I do believe it will end in the near future. To be honest, I think that Ukrainians have more hatred toward Russians [than vice versa], because they have more grounds for it; for Russians, the propaganda works, but there is no visceral, human, instinctive hatred, and when all this darkness ends, we will be friends again and feel an affinity toward each other. During the big war with Germany, which I remember well, we all hated Germans and the German language. But now, people I know happily travel to Germany and interact with Germans, and the Germans don’t seem so bad. Propaganda does have a way of turning people into beasts. It even did that to a people as European as the Germans—but now, they’ve changed completely. . . . Of course people who follow criminal orders are not completely relieved from responsibility, but soldiers are usually poorly educated people, they don’t know any of this, and besides, when propaganda keeps telling them: look, here are enemies who kill people for speaking or thinking in Russian—this stokes anger. . . . The blame always rests with the leader, you see. And when it’s over, Ukrainians will gradually forgive Russians, just as we forgave the Germans.

Of course, this was said nearly four years before the start of a full-scale, no longer localized war in which a Russian invading force bombed Ukrainian cities, reducing some of them to rubble, and committed unspeakable atrocities in occupied territories.

The Crimson Pelican leans toward a pessimistic view of the Russian people, who are seen as mired in a degrading passivity. Today, Voinovich’s savagely satirical vision of the Russian masses submitting to “universal shafting” seems especially timely in view of Russia’s slide toward what is likely to be universal mobilization, with only sporadic resistance so far. And yet in his interviews, Voinovich remained stubbornly optimistic. As he told Ukrinform:

That was satire, hyperbole. The book is a warning. In The Crimson Pelican, as before in Moscow 2042, I’m saying: People, this is what will happen to you if you continue living as before . . . No, personally, I have not lost faith in the Russian people. It is certainly displaying miracles of patience, but I don’t think it’s hopeless. Huge change did happen after all some time ago, in 1991; at the time, Russia took a step towards democracy. Such events are coming once again, and I think they will definitely happen. Russia will eventually follow the same path as Ukraine is following now—so far, unfortunately, with great difficulty.

Notably, in several interviews, Voinovich also predicted the possible breakup of the Russian Federation—something that is increasingly seen as a realistic scenario today. It is perhaps worth noting that in Moscow 2042, the futuristic regime that represents a melding of KGB and church runs a rump state known as “Moscorep”—a portmanteau of Moscow Communist Republic—and consisting only of Moscow and its environs.

Some aspects of today’s tragic reality seem to mirror Voinovich’s absurd hyperbole. (The Crimson Pelican depicts its Putin figure incubating pelican eggs while seated at his desk; is the real Putin’s much-memed penchant for bizarrely long tables any less ridiculous?) In other ways, the reality may have outstripped the satire: Would even Voinovich have envisioned a Putin associate openly recruiting criminals in a penal colony to fight with a “private” military (i.e. mercenary) unit in Ukraine? Or the high-speed referendums at gunpoint intended to justify the annexation of several occupied regions of Ukraine even as these supposed new Russian lands keep shrinking under the onslaught of Ukrainian forces? Or hundreds of thousands of Russians fleeing to places like Mongolia and Kazakhstan to escape a draft? And yet one can also see glimmers of hope in the dark present: the fleeing potential conscripts may not be heroic resisters, but at least they are not duly reporting for the “shafting.”

One can only imagine what Voinovich would have made of Russia’s, and Ukraine’s, present moment. His clear-headed and humane vision is sorely missed, and given how vigorous his intelligence and creativity remained to the end, his death still feels untimely.

In Putin’s Russia of 2022, celebrating Voinovich’s legacy is itself an act of heresy. And yet some Russian media outlets have done that. Nezavisimaya Gazeta ran a piece by Alisa Ganiyeva pointedly titled, “He didn’t live to see this day. We have,” which explicitly linked Voinovich’s vision to the horrors of the present day:

He died four years short of this anniversary. This invites an awful question: “And maybe it’s a good thing that he did?” No, it’s a bad thing, a terrible pity. Today, the voice of a living Vladimir Voinovich (1932-2018) would have been salutary, a source of moral sustenance.

Quoting from a 2012 interview in which Voinovich said that “the stupidity and vulgarity” of modern-day Russia had “exceeded all satire, even unwritten,” Ganiyeva continues:

Another 10 years have passed, and the correctness of his words has increased a hundredfold. Modern reality transcends the most psychedelic, ridiculous, and fantastical miasmas of artistic imagination. Imagined reality is somehow bleeding into the actual one, blurring the boundaries between the real and the unreal.

And, quoting another Voinovich prediction of new “big events,” she concludes: “He was right. The big events have come. He did not live to see them; we have. As for the kind of mess we’ll have to clean up, no literature has yet described it.”

An essay in the Literary Gazette by Evgeny Popov, pointedly titled “He remained free,” ends on an even more pointed note: “Power changes, writers remain.”

Only time will tell whether Russia’s future will justify Voinovich’s civic optimism or the pessimism of his fantastic vision. In the meantime, Voinovich is overdue (as I wrote four years ago) for a rediscovery in the West—both as a brilliant writer whose work transcend its cultural and political specifics, and a voice of true liberalism and tolerance that represents a better future for Russia and the world.