The Pro-Wrestling Presidency Keeps Working the Marks

In Florida, professional wrestlers are now essential workers. Go figure.

In Florida professional wrestlers are now essential workers. No, really. On April 9, Gov. Ron DeSantis filed an amended version of his state’s “State at Home” order, with an exception for:

Employees at a professional sports and media production with a national audience—including any athletes, entertainers, production team, executive team, media team, and any others necessary to facilitate including services supporting such production—only if the location is closed to the general public.

The news broke last Monday during a press conference by Orange County Mayor Jerry Demings and while it might have seemed ludicrous, it wasn’t especially surprising.

That’s because Orange County, Florida is home to World Wrestling Entertainment’s Performance Center and Full Sail University. You may never have heard of these two institutions, but they are critical to WWE’s survival. People who follow the wrestling industry understood that the company’s chairman, Vince McMahon was up to something.

The WWE is the biggest entity in professional wrestling. It is so big, actually, that it’s close to the truth to say that the WWE is professional wrestling in roughly the same way that Barnum & Bailey is the circus.

And the COVID-19 pandemic has become an existential threat to the WWE.

The economics of professional wrestling are built upon four pillars: (1) The gate attendance from weekly televised live shows in giant arenas; as well as non-televised house shows. (2) The sale of merchandise at these live shows. (3) The broadcast rights for these live shows, currently contracted to the USA Network and Fox. (4) Subscriptions to the company’s over-the-top streaming service, the WWE network.

The social distancing measures required by the pandemic have obliterated two of those revenue streams and threatened a third, since it is likely to be a very long time before people will pack into an arena to watch a live sports-entertainment event.

The WWE has tried to adapt.

Since mid-March, the company has been using the small-venue Performance Center as the location for live, empty-house shows of its three weekly programs Raw, SmackDown, and NXT. In early April, the company was forced to move its big yearly showcase, WrestleMania, from Raymond James Stadium in Tampa, to the Performance Center, too.

And then there’s Full Sail University, a for-profit college near Orlando. It has been NXT’s home arena since 2012.

If the Florida state government hadn’t carved out exceptions for wrestlers as essential workers, then even this work-around would have been shut down and the WWE would have ground to a halt.

That’s what McMahon had initially planned for. Wrestling journalist Dave Meltzer initially reported that after the WrestleMania tapings, WWE would spend the Easter weekend taping enough content to fulfill their broadcast obligations through April. But the next day Meltzer published an update saying that McMahon had reversed himself and decreed that the weekly live tapings would continue. Because without live shows, the company might have found itself in breach of contract:

Contracts with both NBC Universal and Fox call for a certain number of shows per year that can be taped. For Raw, that number is three which, at the start of the year, was earmarked for one show over Christmas week and two shows during European tours. In theory, that would leave them with 49 live Raws. Fox has a similar deal.

While nobody will say so publicly, the fear was that by violating the contract, it would give the networks the legal ability to withhold money or find a way to change the deals. With no house shows, the company, like all sports companies, is surviving largely based on television revenue, but the networks paying that are also taking in far less revenue than they projected at this point in time due to the pandemic.

It's unclear whether the decision to return to live is an actual thing that the networks told McMahon to do in recent weeks based on declining ratings or if he is guarding against the possibility of them doing so.

But how did this political deal get done? Days after WWE changed its schedule, two Orlando area journalists reported that Vince McMahon’s wife Linda—the former Trump Small Business Administration administrator, who left her government post to run the pro-Trump SuperPAC, America First Action—would be dropping $18.5 million in ads from her PAC in Florida.

That’s probably a total coincidence.

Also a total coincidence: Vince McMahon being picked to serve on Trump’s panel to reopen American business.

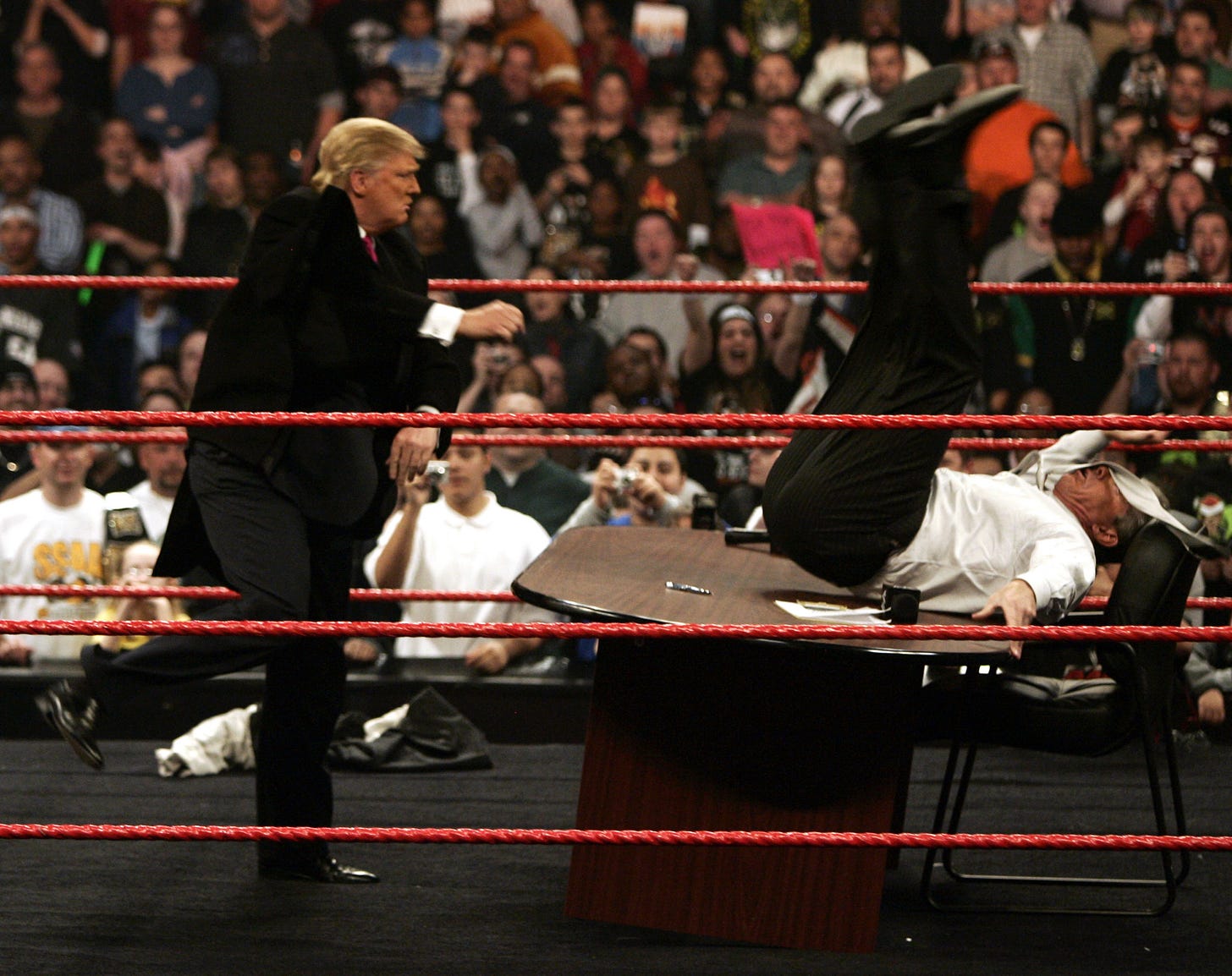

Donald Trump and Vince McMahon have been friends for decades and have often used their businesses to scratch each other’s backs: Trump’s former Atlantic City property hosted both WrestleManias 4 and 5 and the two staged “The Battle of the Billionaires” at WrestleMania 23. McMahon personally inducted Trump into the WWE’s Hall of Fame in 2013.

These connections to pro wrestling explain a lot about the Trump presidency:

The nightly coronavirus “briefings” are really just promos. Political rallies provide his narcissism with the greatest crowd pops he’s had in his life.

Trump’s modus operandi is to constantly put himself over as the victimized babyface.

He’s forever playing to the crowd against whatever heel best fits his needs that day. Sometimes it’s an unknown authority figure (“The Deep State”). Sometimes it’s the announcers (meaning: the media). Sometimes it’s those dastardly foreigners (a classic wrestling trope).

And sometimes Trump decides to go after a governor, like Andrew Cuomo, in a squash match, because he senses that the storyline of another 2,000 Americans dying is getting stale and he needs to generate some heat with the marks.

The entire work would be immensely entertaining, if it didn’t carry real world consequences.