The Real Voting Rights Threat Is Nullification, Not Access

To protect voting rights, we need to acknowledge how much the country has changed since the Voting Rights Act.

Voting rights are alive and well in the United States—but that doesn’t mean we don’t have work to do to ensure they remain so. The 2020 election, held in the middle of a catastrophic pandemic, nonetheless saw higher voter participation rates than any election since 1908. Blacks voted in historically high numbers, especially in eight battleground states, though not quite as high as they did in 2008 and 2012 when the first black president was on the ballot. For the first time, a majority of eligible Hispanic voters also voted in 2020 and Asian American voters increased their participation from previous elections more than any other racial or ethnic group. So why isn’t everyone cheering—including voting rights advocates?

Instead of figuring out how best to make sure the next election sparks as much civic engagement as the last, the right is in a moral panic that expanded access leads to fraud and the left is warning of Jim Crow 2.0 if states attempt to modify any of the procedures put in place in 2020, including those adopted specifically to deal with a pandemic.

I have always believed that voting is not simply a right but a responsibility for every citizen in a democracy. But that responsibility assumes equal access to voting, which has all too often been denied certain individuals because of their race or sex. The 15th Amendment and the Voting Rights Act expanded both the right to vote and enforcement of that right for blacks. The 19th Amendment did the same for women; the Indian Citizenship Act did so for Native Americans in 1924; and the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 gave all Asian immigrants a right to become citizens, entitling them to vote for the first time. This expansion of voting rights has not always been perfectly implemented, and barriers to voting remained in place even after Congress passed laws guaranteeing the rights of all citizens, but the big picture is still a remarkable one of ever-expanding access to the polls.

Still, many Americans don’t vote. Nearly a third of eligible voters did not cast ballots in 2020, and the high mark for voting in the U.S. were two elections in the 19th century. In 1860, an election that determined the fate of the young nation on the brink of civil war, 80.9 percent of eligible voters participated. In 1876, 82.6 percent of eligible voters cast ballots in what arguably stands as the most contentious election in U.S. history, which culminated in an Electoral College fight that makes Republican congressional efforts to hold up certification of the election on January 6 look pale in comparison. It is unlikely that we will ever get to the voting rates of, say, Australia or Sweden, but that does not mean that voting rights are being unduly infringed, much less denied, as some on the left contend.

Which brings us to current efforts to fix American voting laws. What should be our goal? Can we make it easier to vote but ensure that elections are secure; that is, that only those who are entitled to vote are able to cast ballots? And how do we balance one objective against the other?

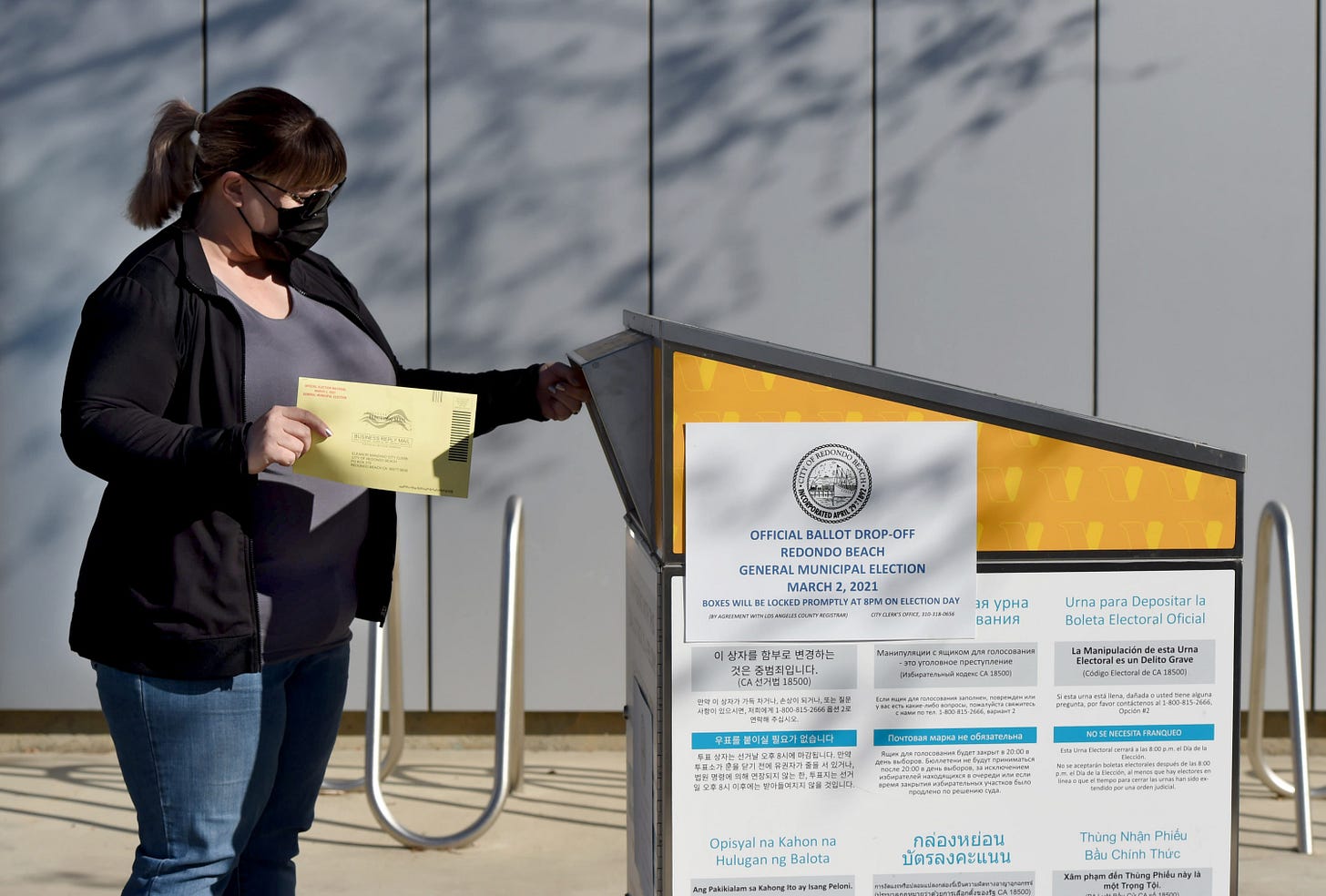

In 2020, some states chose to mail absentee ballots to all registered voters, while others made them available to anyone who requested one, and still others required that voters provide an excuse that fit within parameters set by law or regulation. States also expanded early voting days and allowed voters to drop off mail ballots in specified locations beyond polling places. States varied widely in how they determined which mailed ballots would be counted, with cut-offs determined by postmark in some jurisdictions and, with varying leeway, by the date by which the ballots were received by elections officials in others.

These changes made voting easier, but they also gave critics the chance to cry foul, especially when changes were adopted by appointed officials or by courts rather than by legislation. Compounding the confusion were various rules directing which ballots were tabulated when, with some jurisdictions waiting to count absentee ballots until all in-person ballots were tallied. Disappointed Trump voters watched incredulously while states that seemed to be going for Trump flipped to Biden as absentee votes were tabulated. (This further raises the question of whether the interests of transparency justify releasing misleading, preliminary tallies.) Court after court—62 in all—determined that nothing nefarious was afoot, no evidence of widespread fraud or manipulation. But once raised, suspicions lingered and were fed by a non-stop avalanche of lies and conspiracies spouted by Donald Trump and those hoping to please him so that as of May, 53 percent of Republicans still believed Trump won the election and is the legitimate president.

Although the Constitution provides that states set the time, place, and manner of voting, it also allows Congress to pre-empt state laws, something Congress has done a number of times, including most dramatically in the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The VRA remains the single most effective civil rights law ever passed, and its protections shaped modern American politics. Many on the left and in the media have criticized two recent Supreme Court decisions as “gutting” the VRA, but this claim misconstrues the law, denies it the credit of its astounding success, and overlooks or ignores the enormous change that has taken place in the 56 years since its enactment. To assert that the America that black voters experienced in 1965, especially in the South, is the same as today is either shockingly ignorant or willfully dishonest.

In 1962, registration among eligible black voters in Mississippi was 6.7 percent; by 1967, after passage of the VRA, black registration had jumped to 60 percent. Mississippi and other states of the former Confederacy had prevented blacks from voting by a variety of means, including poll taxes and so-called grandfather clauses, but perhaps the most effective device was the literacy test. In the 19th and 20th centuries, literacy tests were also used to disenfranchise naturalized immigrants in Northern states, many of whom were not fully literate. But the implementation of Southern literacy tests had little to do with ensuring that prospective voters could read a ballot. As the late historian of voting rights Abigail Thernstrom wrote in her excellent book Whose Votes Count?, “In the 1960s Southern registrars were observed testing black applicants on such matters as the number of bubbles in a soap bar, the news contained in the Peking Daily, the meaning of obscure passages in state constitutions, and the definition of terms such as habeas corpus.”

The VRA, specifically Sections 4 and 5, established a specific formula to deter such discriminatory action. As Thernstrom describes it, “The statute thus identified a voting rights violation whenever total voter registration or turnout in the presidential election of 1964 fell below 50 percent and a literacy test was used to screen potential registrants.” The law suspended literacy tests for five years in the identified jurisdictions (which became a permanent, nationwide ban in 1970), but more importantly subjected covered jurisdictions to a radical but necessary requirement that they could implement no new “voting qualification or prerequisite to voting, or standard, practice or procedure with respect to voting” without approval of either the U.S. Attorney General or the District Court for the District of Columbia.

The law’s most onerous provisions, however, were designed to be temporary, requiring multiple extensions over the ensuing decades—amendments to the act that not only extended temporary provisions but greatly expanded covered jurisdictions by redefining literacy tests to include ballots printed only in English in jurisdictions in which more than 5 percent of voting-age citizens were of a single “language-minority” group.

The VRA was amended in 1970, 1975, 1982, 1992, and 2006 (the last extension for 25 years), each time extending the “temporary provisions” that gave extraordinary power to the Justice Department to pre-clear any voting, annexation, or redistricting changes in an expanded set of jurisdictions, including the entire states of Alaska, Arizona, and Texas, as well as specific counties in California, Colorado, Florida, New Mexico, New York, Oklahoma, and South Dakota.

In 1982, however, Congress amended one of the VRA’s permanent provisions of the law in a subtle but quite profound way. The original act’s Section 2 language was succinct and clear: “No voting qualification or prerequisite to voting, or standard, practice, or procedure shall be imposed by any state or political subdivision to deny or abridge the right of any citizen of the United States to vote on account of race or color.” But in 1982, the amendment of Section 2 not only made the law wordy and imprecise, but dramatically changed its purpose from protecting individuals’ equal access to cast ballots to guaranteeing racial and language groups the right “to elect representatives of their choice.” It is these two sets of VRA provisions that the U.S. Supreme Court narrowed in Shelby v. Holder (2013) and Brnovich v. Democratic National Committee (2021).

In 1965, Southern states routinely denied blacks access to the polls, and Congress rightfully worried that any voting rights law it passed might be subverted by recalcitrant state officials who would simply change the rules to undermine its effectiveness, which is why the draconian preclearance provisions of Section 5 were justified. But by the time Shelby was decided, it could hardly be argued that blacks were systematically being denied the right to vote in any state, including Alabama, in which Shelby County is situated. By 2012, in five of the six states originally covered by Section 5 of the VRA, black voter participation exceeded that of whites, with the sixth state showing only a half a percent difference in voter participation between whites and blacks. As Chief Justice John Roberts wrote for the majority in Shelby, conditions in 2012 were not what they were nearly five decades earlier when the formula devised for coverage and the requirement of preclearance: “Our country has changed, and while any racial discrimination in voting is too much, Congress must ensure that the legislation it passes to remedy that problem speaks to current conditions.” Failure to recognize those changed conditions does not advance the cause of civil rights but merely perpetuates anger and grievance. Congress’s failure to update voting rights protections should not be blamed on the Court or the VRA.

So, too, the decision in Brnovich is not the attack on voting rights its detractors claim. (In full disclosure, the Center for Equal Opportunity, which I founded and chair, filed amicus briefs in both Shelby and Brnovich on the winning side.) Arizona has relatively generous voting rules, making it easy to cast ballots in-person on Election Day or up to 27 days days earlier by mail ballot. The question before the Court was whether two provisions in Arizona law ran afoul of Section 2 prohibitions that, in the words of Section 2 as amended, “the totality of the circumstances” show that the law “result[ed] in a denial or abridgment of the right of any citizen of the United States to vote on account of race or color.”

The Arizona laws in question required voters to cast ballots in the precinct or polling center in the county in which they were registered on Election Day and made it a crime for anyone other than a postal worker, elections official, family or household member, or caregiver to collect a ballot during early voting. These requirements and prohibitions may or may not be good policy, but the question before the Court was whether the totality of the circumstances suggested their purpose or effect was to disenfranchise certain voters because of race, color, or language minority status. The evidence the DNC offered for this proposition was deemed inadequate. They failed to show that the state intended to discriminate against minority voters when it enacted the law; and even under the more capacious standard of whether the law had the effect of denying or abridging the rights of such voters, the evidence was exceedingly thin. Out-of-precinct voting resulted in .5 percent of white voters’ ballots not being counted and 1 percent of ballots cast by blacks, Hispanics, and Native Americans—a small differential. The majority opinion, written by Justice Samuel Alito, is exhaustive and counters the arguments of the three dissenting justices well. It is worth the read.

It may well be time for Congress to act to make voting rules more consistent nationwide—and it has the authority to do so. But the biggest threat to democracy now is less that voting laws are too restrictive than it is that votes, once lawfully cast, are counted and the results accepted by losers as well as winners. The strength of democracy rests on the acceptance of election results, win or lose. Laws currently under consideration that would throw election results into question and allow state legislatures to reject them are a serious problem that undermines the future of our democracy. Instead of trying to re-write the VRA to overturn court decisions that were anything but radical, democracy advocates should concentrate on limiting the power of partisan losers to overturn the will of the people.