The Rushdie Controversy, for a New Generation

Fatwa, fear, and free speech—here’s what really matters in the Rushdie story.

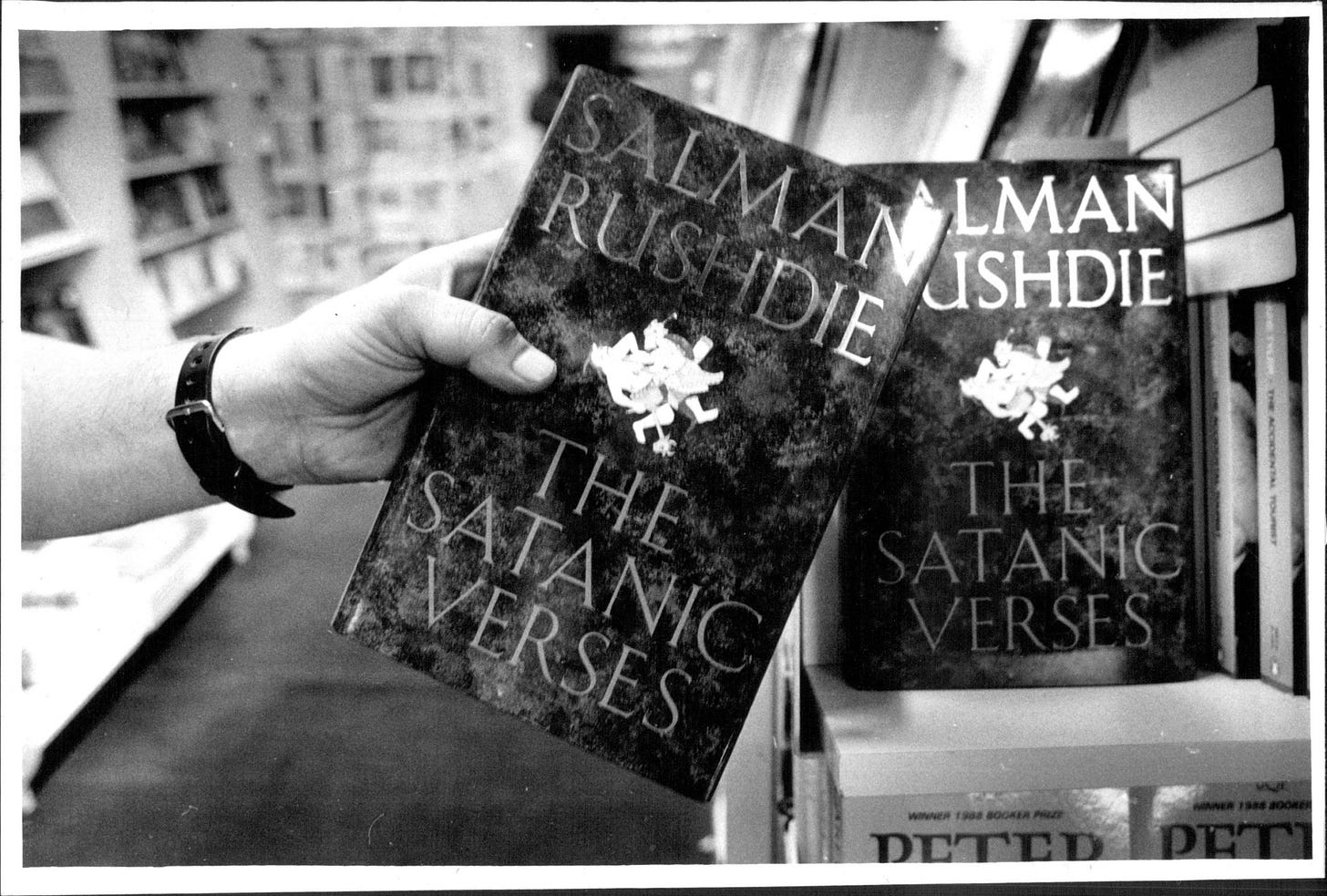

Salman Rushdie’s novel The Satanic Verses was published in 1988, and Iranian Supreme Leader Ruhollah Khomeini’s fatwa ordering all Muslims to try to kill Rushdie was issued issued the following year. In other words, the Satanic Verses conflagration is as much a part of history as the fall of the Berlin Wall or Tiananmen Square—but history that came roaring back on August 12, when a man born almost a decade after The Satanic Verses was published ran onto a stage where Rushdie was about to speak in Chautauqua, New York, and repeatedly stabbed the 75-year-old author in the face, neck, and abdomen. Though his condition has stabilized, his agent reported that “Salman will likely lose one eye; the nerves in his arm were severed; and his liver was stabbed and damaged.”

While Rushdie managed to evade such an attack for decades, a glut of violence followed the release of The Satanic Verses: a dozen people were killed during riots in Bombay, several others in Kashmir, and six more in Islamabad. The Japanese translator of The Satanic Verses, Hitoshi Igarashi, was stabbed to death. An Italian translator, Ettore Capriolo, was also stabbed, and the book’s Norwegian publisher, William Nygaard, was shot three times. Now that Rushdie himself has been savagely attacked by an assailant who will almost certainly prove to be a self-appointed executor of the fatwa (though he may have been in contact with members of Iran’s Revolutionary Guard Corps), it’s worth revisiting just how fully many liberals surrendered to theocracy in 1989 and the years that followed. Younger readers not already familiar with the Rushdie controversy will find that it raises enduring questions about free speech, self-censorship, cultural tolerance, and the distinction between words and physical violence.

In a March 1989 article for the New York Times titled “Rushdie’s Book Is an Insult,” former President Jimmy Carter accused the author of cynically attempting to capitalize on a “horrified reaction throughout the Islamic world” and argued that Rushdie had inflicted an “intercultural wound that is difficult to heal.” Carter said Western leaders should offer “no endorsement of an insult to the sacred beliefs of our Moslem friends,” attacked Rushdie for “vilifying the Prophet Mohammed and defaming the Holy Koran,” and explained that “we should be sensitive to the concern and anger that prevails even among the more moderate Moslems.” These arguments were representative of a broad swath of liberal opinion at the time.

Anxiety about The Satanic Verses was often presented as a paean to multiculturalism or an argument for “sensitivity,” but it was also an expression of fear. Within days of Khomeini’s fatwa, Waldenbooks, B. Dalton, and Barnes & Noble announced that they would no longer sell The Satanic Verses. As a result, American consumers would no longer be able to purchase the novel at chains that accounted for between 20 and 30 percent of all book sales in the United States. At the same time, Coles Book Stores Ltd. in Canada decided not to stock The Satanic Verses, while at the behest of a Muslim group the Canadian Revenue Agency halted importation of the book to review whether it fell afoul of laws on “hate literature.” The CEO of B. Dalton was blunt about the company’s decision to pull the book: “It is regrettable that a foreign government has been able to hold hostage our most sacred First Amendment principle.”

Four years after Khomeini issued the fatwa, a French publisher released Pour Rushdie: Cent intellectuels arabes et musulmans pour la liberté d’expression. An English edition was published the following year: For Rushdie: Essays by Arab and Muslim Writers in Defense of Free Speech. In his contribution, “Against the Orthodoxies,” the influential Palestinian-American social critic Edward Said wrote of the controversy, “It is not only a ‘case,’ but a man and a book.” Said reminded readers that the fatwa was more than an “occasional item on the news” or a case study about free speech and cultural conflict. It was an assault on a human being who had “suffered unconscionably”—who lost his “personal life and all personal tranquility” due to the sputtering of an aggrieved theocrat. Other articles and poems in the collection also put the lie to the insulting assumption that the Muslim world privileges religious dogma over free expression. Carter may want to buy a copy.

In one essay, the Saudi sociologist Anouar Abdallah expressed “immense admiration” for Rushdie’s work, but argued that “our support of Rushdie would rest on the principle of freedom of expression, regardless of the intrinsic value of the text being defended.” He attacked the notion that “any ulema, even a famous one” should be “able to issue fatwas that will be carried out by enforcers everywhere.” He ridiculed the idea that the “solutions to the numerous and complicated problems of Iranian society were dependent upon the spilling of the blood of Salman Rushdie.” Explaining that other religious authoritarians (including those in Saudi Arabia) were emulating Khomeini, he emphasized the universality of the principles at stake:

Our insistence upon affirming the freedoms of thought, of expression, and of publication for Rushdie is not aimed merely at assuring the mental and moral equilibrium of this one man. Rather, it also aims to bar the way against all who. . . are both bloodthirsty and apparently prepared to traffic in religion to gain their ends. Rushdie employed his pen only; those who oppose him should reply with logical arguments, not by calling on the sword of the state.

For Rushdie was printed after the riots and assassinations that followed the publication of The Satanic Verses. Its contributors included Iranian writers who were willing to accept the risk of openly defying the theocracy governing their home country—an act of courage and solidarity that exposed the cowardice of many writers, politicians, and booksellers around the world. The Iranian writer Mahshid Amir-Shahy delivered a speech at the League of the Rights of Man in Paris in February 1993, arguing that “Khomeini committed the imprudence of linking the fate of his regime with freedom of expression, not only in Iran itself but in the world at large; this link will prove to be deadly for the regime.” She continued:

We must actively continue both our efforts to defend the rights of Salman Rushdie and to promote the idea of a secular democracy among the Iranians because, believe me, the Iranians have no illusions about the supposed virtues of political Islam. I do not believe we can separate these two causes, and I dare to think, therefore, that we will stand together in this double battle.

Amir-Shahy called for an alliance between intellectuals in the Muslim world and the West, arguing that the former (particularly Iranians) had a responsibility to discredit the brutal, dogmatic ideology of the mullahs and “violate the taboo of its ‘sacrality’ (imposed with whips, stonings, and bombs).” She called for Western intellectuals to “focus their efforts on Western governments, either by direct intervention or by means of influencing public opinion, and get them to call for a complete and unconditional withdrawal of the fatwa.”

President Bill Clinton had been inaugurated six months before Amir-Shahy delivered her speech, though she probably had his predecessor in mind. When Khomeini condemned Rushdie, President George H.W. Bush was more interested in damage control than defending the most fundamental American value. After a week of silence and increasingly intense pressure from organizations such as the Authors Guild and the ACLU, Bush finally declared:

However offensive that book may be, inciting murder and offering rewards for its perpetration are deeply offensive to the norms of civilized behavior. And our position on terrorism is well known. In the light of Iran’s incitement, should any action be taken against American interests, the Government of Iran can expect to be held accountable.

The death sentence itself evidently didn’t rise to the level of an American interest. (Rushdie was born in India and became a British citizen in 1981, then an American citizen in 2016.) Other Bush administration officials were even more pusillanimous: a State Department official warned against “fanning the flames” of the crisis with stronger official statements. Secretary of State James Baker described the fatwa as “regrettable.”

Baker noted that “We endorse the freedom of speech rights,” but he was careful to add that the administration took this position “without endorsing the book. We haven’t read the book, and we’re not, in expressing our displeasure, endorsing some of the statements that might be contained in the book.” This wasn’t a brave or principled stand from the highest-ranking officials in the land of the First Amendment. Writers and dissidents in the Muslim world were willing to take grave risks to support the principles to which the Bush administration paid such feeble lip service.

For Rushdie contains an open letter signed by 127 Iranian writers, artists, academics, journalists, and editors. The letter offered an explicit defense of Rushdie—and basic liberal ideals—that the U.S. government failed to muster:

The signatories of this appeal, who have already manifested their support for Salman Rushdie in various ways, believe that freedom of expression constitutes one of the most precious goods of humanity; and, as Voltaire said, it cannot exist in the true sense unless there is also freedom to blaspheme. No individual and no group has any right to limit this freedom of expression in the name of any sacrality whatsoever.

While it took President Joe Biden longer than several of his counterparts (such as French President Emmanuel Macron) to issue a statement about the attempted assassination of Rushdie, on August 13 he announced that he was “shocked and saddened” by the attack. The statement noted that Rushdie

stands for essential, universal ideals. Truth. Courage. Resilience. The ability to share ideas without fear. These are the building blocks of any free and open society. And today, we reaffirm our commitment to those deeply American values in solidarity with Rushdie and all those who stand for freedom of expression.

This statement was an improvement over Bush’s and Baker’s, but failed to connect the attack to the regime that ordered it 33 years ago—hardly a surprise from a risk-averse president who’s trying to finalize nuclear negotiations and normalize relations with Tehran while also bombing its proxy forces in Syria.

Just days after an attempted theocratic execution of one of our greatest living novelists, desultory expressions of shock and sadness aren’t enough. While Tehran denied any involvement in the attack, a spokesman for the Iranian Foreign Ministry declared: “In this attack, we do not consider anyone other than Salman Rushdie and his supporters worthy of blame and even condemnation.” Secretary of State Antony Blinken called recent comments on Iranian state media “despicable”—he might have been thinking of a proclamation on Jaam-e Jam that “an eye of the Satan has been blinded,” a gruesome reference to the fact that Rushdie may lose his sight in one eye. But the Biden administration should demand exactly what Amir-Shahy called for more than a decade ago: a complete and unconditional renunciation of the fatwa. If the Iranian government argues that the late Khomeini is the only man who could formally rescind the fatwa, it can take other measures, such as preventing any organization from promoting or subsidizing the ransom on Rushdie. In 2012, an Iranian religious foundation offered a $500,000 reward for Rushdie’s murder, bringing the total to $3.3 million. This is barbaric, criminal behavior, and Western governments should demand its end.

Khomeini isn’t the only theocrat who holds a violent veto over what we create, display, and publish. In 2009, Kenan Malik observed in From Fatwa to Jihad: The Rushdie Affair and Its Aftermath that liberal democratic societies had “effectively internalized the fatwa.” That was four years after violent protests swept the world yet again, this time in response t the Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten publishing a series of cartoons depicting the Prophet Muhammad. The Danish embassy in Damascus and consulate in Beirut were torched. Riots in many countries left scores dead. Cartoonists and editors were targeted by assassins.

When American media outlets covered the story, they refused to publish pictures of the cartoons in question. A spokesman for Dow Jones & Company said The Wall Street Journal didn’t want to “publish anything that can be perceived as inflammatory to our readers’ culture when it didn’t add anything to the story.” The managing editor of The Chicago Tribune explained that the paper could “communicate to our readers what this is about without running it.” The New York Times reported that

Most television news executives made similar decisions. On Friday CNN ran a disguised version of a cartoon, and on an NBC News program on Thursday, the camera shot depicted only a fragment of the full cartoon. CBS banned the broadcast of the cartoons across the network.”

The same year From Fatwa to Jihad came out, Yale University Press published Jytte Klausen’s The Cartoons That Shook the World, a book about the cartoon controversy—but it refused to include the cartoons themselves. At least the publisher was clear about why:

The Press would never have reached the decision it did on the grounds that some might be offended by portrayals of the Prophet Muhammad. . . The decision rested solely on the experts’ assessments that there existed a substantial likelihood of violence that might take the lives of innocent victims.

During a discussion about the Danish cartoon controversy, Rushdie argued that it was necessary to resist this tendency and actively combat theocratic bullying:

What happens when the subject of violence arises?. . . The subject is no longer about whether you should publish or not publish these things, but about how you respond to violence. Do you respond to it with cowardice or courage? At that point, it seems to me that every newspaper in the world should publish the Danish cartoons. Not because they like them, and not actually because they particularly want to insult Islam. But just to make the point that you don’t give in to threats.

Rushdie made this point again after the Charlie Hebdo massacre in early 2015. The small French satirical magazine had long treated Islam like any other religion, which meant subjecting it to criticism, publishing cartoons about it (including those originally printed in Jyllands-Posten), and refusing to surrender to the mounting threats to staffers—some of whom were already living under police protection before the attack. A few months after a pair of jihadists walked into the paper’s Paris office and opened fire, killing a dozen people and wounding several others, PEN America announced that Charlie Hebdo would receive an award for its courageous commitment to free expression. Rather than celebrating the Charlie Hebdo editors and cartoonists for defying theocratic censorship, 242 members of PEN denounced the decision. The PEN authors argued that Charlie Hebdo attacked a “marginalized, embattled, and victimized” group when it criticized Islam, which exacerbated “anti-Islamic, anti-Maghreb, anti-Arab sentiments.”

Rushdie argued that the signatories were “horribly wrong” and said: “If PEN as a free speech organization can’t defend and celebrate people who have been murdered for drawing pictures, then frankly the organization is not worth the name.” Unlike so many American organizations over the past several decades, PEN stood firm in its defense of free expression. Of the authors who demanded a different outcome, Rushdie said: “If the attacks against Satanic Verses had taken place today, these people would not have defended me, and would have used the same arguments against me, accusing me of insulting an ethnic and cultural minority.” In a sense, this is evidence that we’ve internalized the fatwa in an even deeper way—instead of refusing to print or display potentially offensive material, many argue that the material shouldn’t be produced in the first place. They tell themselves this self-censorship is just and necessary.

After decades as one of the world’s most courageous champions of free expression, Rushdie is in critical condition because a would-be assassin obeyed the command of a long-dead religious dictator to kill him for writing a novel. One reason his life has been in danger for the past 33 years is the fact that so many people are afraid to do what he has done: stand up to religious totalitarians and fight for the universal right to free expression, especially for those who live under oppressive and intolerant regimes. The least we can do now is show a bit of courage on his behalf and stand by his side in the fight to come.