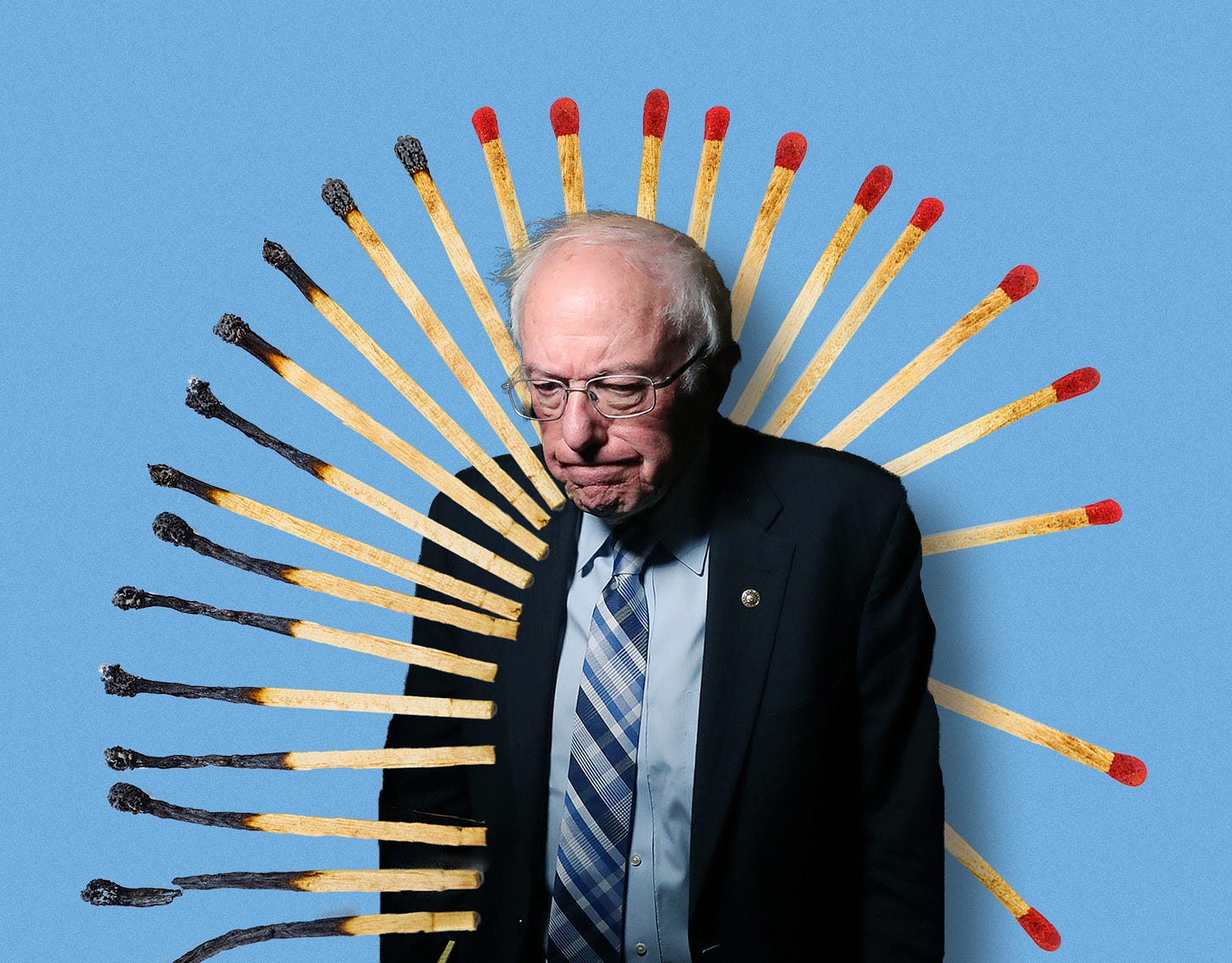

The Sanders Campaign Is a Menace to Public Health

Bernie Sanders can't beat Joe Biden. But he can force millions of people to risk being exposed to the coronavirus.

On Tuesday night Bernie Sanders lost three more states, all of them large. In Arizona he was on track to lose by double-digits. In Illinois he was defeated by more than 20 points. In Florida his deficit was double that. He received barely 20 percent and lost every single county.

Florida—you may have heard this before—is an electoral hinge in which every winning Democratic presidential campaign of the last 50 years has been at least competitive.

So Bernie’s campaign is over. It has been over since Super Tuesday. And yet, he persists.

A vanity campaign that continues onward despite having no path to victory aside from the other guy dropping dead is usually a nuisance. For example, Jerry Brown in 1992. Ron Paul in 2012. Sometimes, if the candidate and his supporters are particularly aggressive and unpleasant, it can be a hindrance that exacerbates intra-party divisions and does active harm to the party’s nominee. For example, Ted Kennedy in 1980.

But in continuing his campaign today, the Sanders 2020 campaign has become something entirely new in modern politics: A threat to public—and civic—health.

And if he does not suspend his campaign, immediately, then he and his supporters should be shamed and shunned.

The first part of this equation is understanding exactly how thoroughly defeated Sanders is.

Joe Biden has beaten him in every type of state, from Washington to Mississippi, from Minnesota to Massachusetts. From Texas to Virginia to Idaho.

Joe Biden has beaten Sanders among nearly every demographic other than “people under 35”: black, white, college-educated, non-college, urban, rural, suburban, professional, blue-collar.

Joe Biden has won in most places by wide margins—his average margin of victory over the last nine contests has been close to 20 points.

But Joe Biden has not yet reached the 1,991 delegate threshold required to mathematically clinch the nomination. And since delegates are being awarded proportionally, he might not cross that line until the end of April—and even this assumes that the votes are held roughly as scheduled.

As a theoretical matter, Sanders can keep campaigning until then by claiming that the race has not yet been decided. But it has. Even if Biden were hit by a bus tomorrow, his lead is substantial enough that he’d probably still wind up with more delegates at the end of the campaign than Sanders.

In a normal time, if Bernie Sanders wanted to stay in the race until he was mathematically eliminated, that would be his prerogative.

Heck, if he stayed in the race even after he was mathematically eliminated—say, because he wanted to keep his issues alive, or because he wanted to let all Democrats have their votes counted—that would be fine, too.

And if Sanders wanted to go on a scorched-earth campaign against Biden designed to make him radioactive for the general election—purely out of spite? No problem. All’s fair.

But this is not a normal time. We are in the midst of a global pandemic. America is adopting desperate measures—like voluntary quarantines and the elimination of communal events and gatherings—to slow the infection rate of COVID-19. Many of these measures are hurting the broader economy and will create societal pain down the road even if they work.

Voting is a communal activity.

In order to have an election, a bunch of volunteers—most of them well over the age of 35—get together in a firehouse or a school cafeteria. They then interact with a steady stream of people at close range for a day. These people hand objects to the volunteers (driver licenses, voting ID cards) and are then handed other objects (ballots or forms) in return. They stand within arm’s length of one another. And if the turnout is heavy, the voters stand in a line, waiting as a group.

Maybe this isn’t the Dulles airport petri dish, but it isn’t best-practices, either.

Could you and 30 other people manage voting interactions without engaging in risky behaviors? Sure. But when you scale the number of interactions out to a couple million people—which is roughly how many Democrats voted on Tuesday—there are going to be moments of incidental contact and carelessness.

And if you scale it out to several million more voters—which is the number of people who will have to go to the polls in order to formally lock down the nomination? The entire process is simply daring the coronavirus to propagate.

This would be a risk worth taking if we were talking about a real election with real implications for the future. Our democracy is precious and we should not allow it to be overrun by emergencies.

But that is not what is happening at this moment. Any Democratic primaries being held from this point on are merely formalities made necessary by Sanders’s refusal to bow to reality and drop out of a race that is already decided.

He has created a public health risk for no good reason. Shame on him. And shame on his supporters for not demanding that he pack it in for the good of the country.

That’s the public-health side of things. There’s a civic-health side, too.

Over the last 72 hours, the state of Ohio saw a legal crisis related to its primary. The Ohio Democratic primary was originally scheduled for Tuesday.

On Monday morning, Ohio governor Mike DeWine asked a state court to move the primary to June because of health concerns. The judge denied the request, saying it would create a “terrible precedent.” So the primary was moving forward.

Late Monday night, DeWine tweeted that he intended to ignore the court’s ruling and that he believed the director of the state’s health department would order the polls closed by fiat.

This created a dangerous situation. Okay, it’s not really dangerous in the immediate sense—the Ohio primary didn’t matter because it was just going to be another blowout Biden victory.

But it does matter that we’re now moving into territory where incumbent executives believe that they can ignore a court order and do whatever they see fit regarding the rescheduling of an election.

It does not take a great deal of imagination to see how a scenario very much like this one might anticipate a constitutional crisis eight months from now.

In the case of Ohio, the state Supreme Court bailed out the governor: Early Tuesday morning, not long before polls were to open, the court issued an unsigned ruling essentially blessing DeWine’s power grab. Which, all things considered, was probably for the best. Because the alternative would have been ruling against the governor after he had acted—thus proving that the judiciary is ultimately powerless against a highly motivated chief executive.

Which is . . . not a great precedent.

If America is very lucky, we will not add a constitutional crisis to our health crisis and our economic crisis.

But by continuing his dead-end campaign, Bernie Sanders gave us a little preview of what the weeks ahead might look like. If he continues to persist, there may be more instances where governors show that they can do what they will with the timing of elections, the courts be damned. Instances that—I promise you—the biggest chief executive of them all will be watching.

There’s no shame in losing a campaign. There is a great deal of shame in what Bernie Sanders is doing right now. He is harming America. He should stop.

Today.