The Talibanized Afghanistan Will Inspire and Attract Radicalism

Extremist movements do become more moderate, but it seems unlikely the Taliban will.

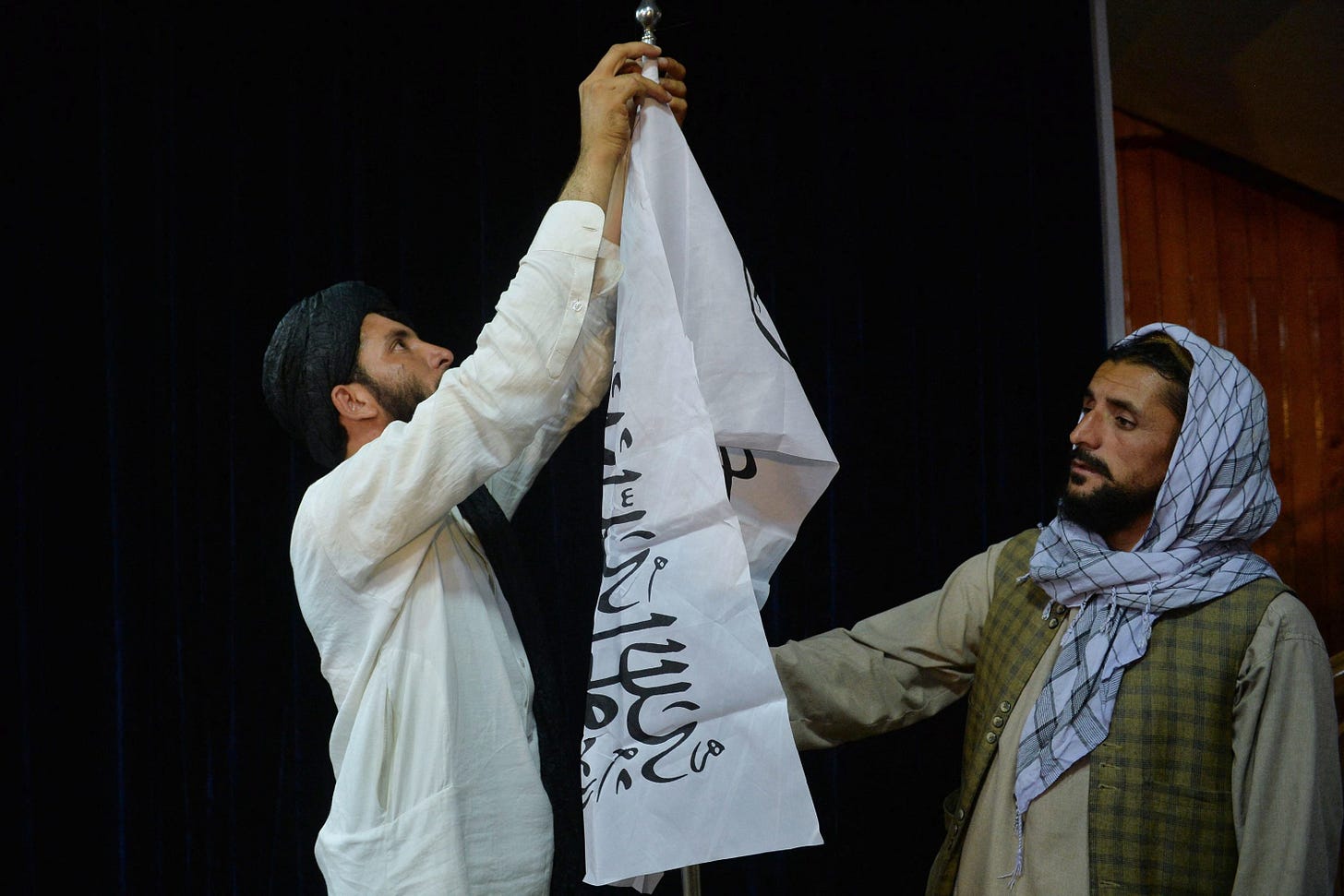

As the reforming Afghan state vanished away, and horrifying airport scenes affronted our eyes, this week’s worries have been: Will the Taliban host al Qaeda or other terrorist groups? And will they again impose tribal severities on modernizing Afghans? Probably they will, before long, but two great dangers are not receiving the consideration they deserve.

First there is the inspirational effect of the Taliban victory. When the Shah fled from Tehran in 1979, one of my graduate students, a Saudi Sunni, told me excitedly “Iran has given us hope.” That hope eventually dried up, but for years, most of the subsequent Muslim extremist violence, whether Shi’ite or Sunni, was fired by the Iranian example. Similarly, when the “Islamic State” took over much of Syria and a vast zone of Iraq, it had a galvanizing effect on jihadists; converts from Europe as well as across the Muslim world began gushing into its new caliphate, eager for terrorist missions. We can expect something similar soon in Afghanistan.

These inspirational effects are not only contemporary, or only Muslim. With the unexpected triumph of the Red Army over Germany in 1942-45, fireworks exploded in a dark sky for Europeans already pushed to the left by fascism. Huge French and Italian Communist parties became real contenders for power, for the first time. Communist revolutions took Yugoslavia and Albania; Greece nearly followed. Such inspirations spread wide in time and space. As documented by Simon Schama, the American Revolution inspired the French Revolution.

It is simply human nature: Sudden, total success sparks euphoria and imitation. President Biden’s national security team, accustomed to the routine, sluggish pace of the “interagency process” and NATO decision-making by consensus, seems unaware of this basic psychology. As recently as the Thursday before the fall of Kabul, the administration was briefing the press that, as Axios put it, “Biden’s diplomatic team in Doha, Qatar, was trying to talk sense into the Taliban” (emphasis added).

The second problem is that the United States created a somewhat modern state in part of Afghanistan over the last twenty years, with a massively equipped army and air force. Now Trump’s announcement of withdrawal and Biden’s decision to actually pull out the last remaining U.S. troops without serious planning have delivered this somewhat modernized state to the Taliban. So in effect Trump and Biden agreed to create another jihadist state in the Middle East.

There have been a handful of jihadist states over the last half century, including the Islamic Republic of Iran and the Islamic State caliphate, the latter now destroyed at great cost. Iran has created endless trouble for the United States because it was already a state with an army, borders, and international recognition, not a patch of desert where someone hoped to raise a caliphate. Now, with the return to power of the Taliban in Afghanistan, we may have another Iran to contend with for years, though it depends on the competence and tactical moderation the Taliban can develop. Such a state will not lack opportunities. Just to begin, the row of Central Asian countries on its border are some of the most unpopular tyrannies in the world, and the weakest. They have suppressed traditional Islam with particular brutality.

The Taliban has announced its moderate intentions—but it is known for broken promises. Moreover, the bigger problem is in the very logic of extremism. I am writing a book on how extremist movements change, and we can learn from some patterns since the eighth century. Extremist movements do become more moderate. But it happens only after early, quick defeats—such as that of the Anabaptists in Reformation Germany—or after years and years with a sense of failure, as we saw with Gorbachev. Moderation doesn’t come in the flush of success.

The hope to conciliate newly triumphant extremism was exactly the hope some officials felt with the Islamic Revolution in Iran and with Hamas. It was also hope of Chamberlain and Daladier with Hitler. It fails again and again. Presidents Trump and Biden certainly had reasons to give up weak allies, but doing so, they leave us, as in 1938, with the same threat and less prepared to meet it.

The worst of it is that these two factors will make each other worse. A jihadist state is much more inspiring than a jihadist movement—witness again ISIL. Statehood is a matter of prestige: for a long time now Islamist movements have defined the creation of an “Islamic state” as their goal and standard for achievement. A state provides a better terrorist sanctuary, and has far more versatile capabilities, than a movement.

After the surly tantrums of the Trump years, America and the free world need a calm, confident, successful Biden presidency. But President Biden chose to trigger all the instabilities in a stalemated, low-cost policy problem, tipping it into catastrophe. If he is to live down this self-inflicted wound he must dismiss important advisers, reorganize the intelligence bureaucracy, and rethink his international direction.