The Trump Primary Has Already Begun

When sitting presidents are unpopular and have politically unsuccessful first terms, a primary challenge is the norm, not the exception.

The smartest thing Barack Obama ever did was running for president when everyone thought Hillary Clinton was invincible.

The second smartest thing he did was invite Clinton into his Cabinet and keep her there through his first term. Obama understood that avoiding a primary challenge is a necessary (though not sufficient) condition for re-election. And he knew that Hillary Clinton had her own political power base. Which meant that if things went south during Obama’s first term, the safest place to warehouse Clinton was inside his administration.

And things did go south during Obama’s first term. There was no economic prosperity. His major legislative accomplishment was deeply unpopular. His party lost 63 House seats in the midterm elections and lost the House popular vote by 6 million votes. Every normal indicator suggested that Obama could have drawn a primary challenge in 2012—except that he and David Axelrod went to great lengths to court and stroke Democrats in order to avoid one.

President Trump, on the other hand, seems to be daring someone to run against him in 2020. He frequently insults his fellow Republicans and has made almost no effort to mend fences with the segments of the party that have been hostile to him. (See “Mia Love gave me no love.”) He did not bring the people most likely to run against him—John Kasich and Mitt Romney—into his administration. And he has not kept the people who would be most dangerous to him—Nikki Haley and Jim Mattis—on his team. If you only looked at this top-line data, you’d almost think Trump wants a primary challenger.

Maybe he does. Say what you will about Trump’s political instincts, but his media instincts are quite deep. It’s possible that Trump believes that having a primary opponent will keep him in the news while a potentially crowded Democratic primary looms over the television landscape and that the prospect of having a squash match,where the sitting president overwhelms some underfunded pretender, will signal electoral strength to marginal Republican voters and help keep them engaged for the general.

And for all we know, maybe he’s right. It’s not like American politics has been following the traditional laws of physics as we’ve known them for the last 40 years.

But before we start assigning 4-D Chess Grand Master status to Trump, we ought to establish two things: (1) Primary challenges are not, in fact, extraordinary insurrections incited by deranged elements within the party. And (2) whether a primary challenge is a cause or a symptom, it usually correlates with a failed re-election bid.

You can imagine that if Trump is challenged, the first thing the Julie Kellys and Mollie Hemingways of the world will say is that his challenger represents another paroxysm of NeverTrump insanity. As a historical matter, this argument would be false. When sitting presidents are unpopular and have politically unsuccessful first terms, a primary challenge is the norm, not the exception. And as for the second matter, anyone who wants to claim that a Republican challenger actually helps Trump will have have to argue the four most dangerous words in the English language: “This time is different.”

Good luck with that.

The modern political age more or less begins with the advent of televised politics in the 1960s. Since then we’ve had nine sitting presidents stand for re-election. Five of them were challenged in the primaries. Of those five, only one—Richard Nixon in 1972—won.

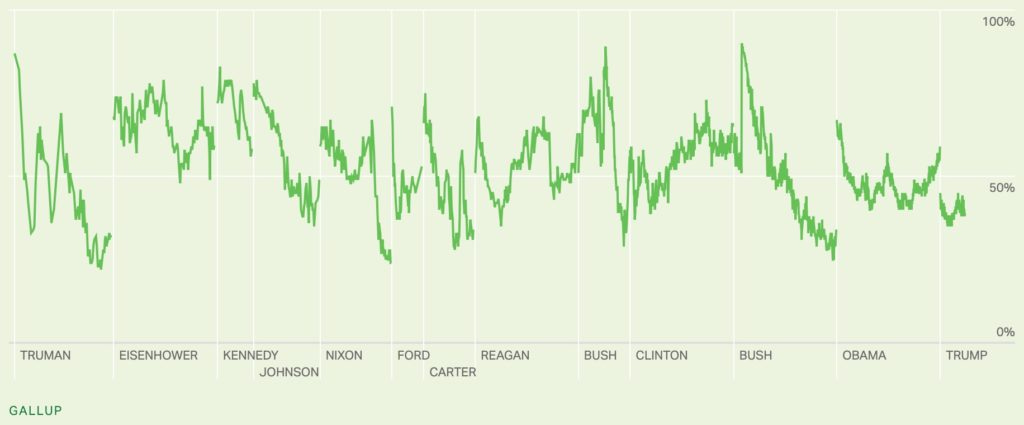

When you look at the data on presidential approval ratings, a few things stand out. Not all of the presidents to draw primary challenges were terribly unpopular. George H.W. Bush, for instance, was at close to 60 percent approval at this point in the cycle. (This was an artificial level created by the Gulf War, obviously.) But most were under the 50 percent mark and trending downward. The presidents who avoided primaries—Reagan, Clinton, George W. Bush, and Obama—generally had approval rates above 45 percent and generally trended upward leading into the re-elect year.

Look at the graph below and you’ll note that 45 percent is a mark Trump hasn’t yet touched. His average has remained closer to 40 percent and there is virtually no directional trend: He has topped out, once or twice, at 44 percent and bottomed out, more than a few times, at 36 percent. His range of possible outcomes here seems locked into a very narrow band. In order for him to break out of it, something extraordinary would have to happen.

Have you seen anything in the last three years to suggest that Donald Trump is capable of making himself markedly more popular with the people who don’t already like him?

Me neither.

So if you go by the data and the history of politics, you would assume that the odds of Trump being primaried are actually pretty good—at least better than even. And if it happens it’ll be because Trump has been an unpopular president who did not take steps mend fences and keep potential challengers close to him.

This isn’t rocket science.

Could a primary challenger actually beat Trump? Well, history and the data suggests that the answer is 100 percent, absolutely, a stone-cold, lead-pipe cinch, “no."

Which leads us to a final matter: Would a primary challenge be good for the Republican party? Possibly no. Possibly, yes. If we stipulate that a primary challenge is at least highly correlative with an incumbent losing, then a challenger would not be helping Trump’s re-election cause.

On the other hand, what is good for Trump is not, by definition, necessarily good for the Republican party (or the conservative movement). The long-term interests of the Republican party were not damaged by Pete McCloskey’s 1972 challenge to President Nixon. They were positively bolstered by Ronald Reagan’s 1976 challenge to President Ford. If you would have welcomed the Reagan of 1976, then you have no standing to criticize the Mattis (or Romney, or Kasich, or Candidate X) of 2020.

All of which is to say that a Republican primary challenge to Trump is more likely than not and should be viewed by objective observers as a matter of routine; that there are number of possible candidates who have already been antagonized by President Trump; and that an insurgent challenger might help the institution of the Republican party and the cause of the conservatism in the long term.

Anyone who denies these simple truths is either a huckster or a fool.