The U.S. Government Needs a Budget

Years of disorderly, undisciplined budgeting have let political leaders of both parties avoid inconvenient questions—and exploded our debt.

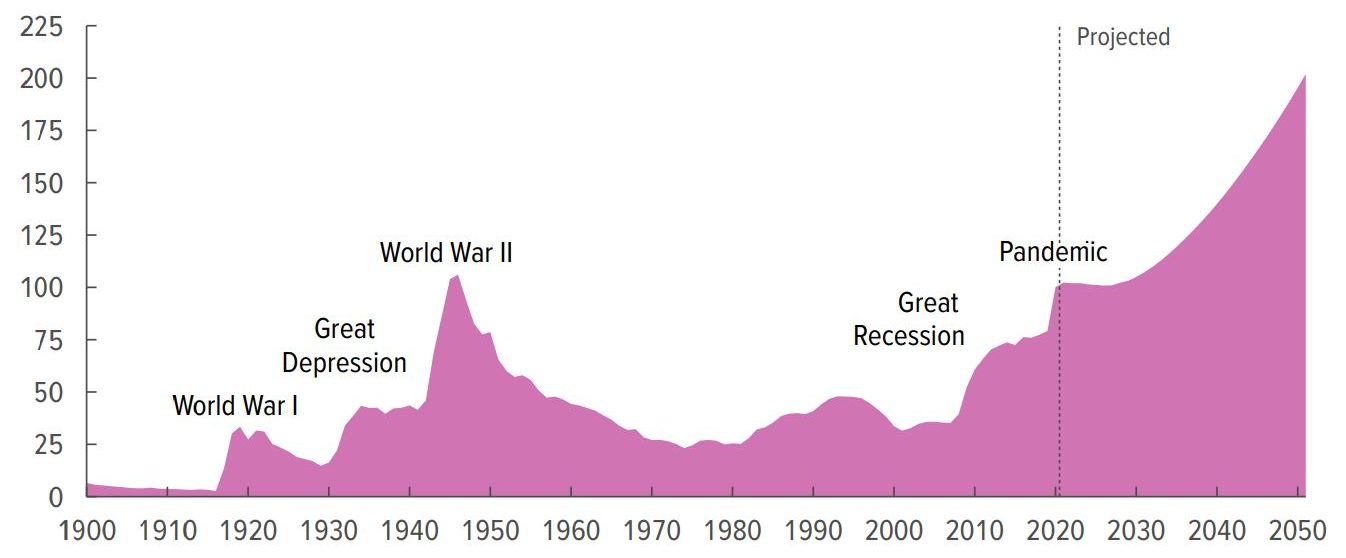

President Joe Biden is pushing an aggressive agenda of ramped-up federal support for traditional infrastructure, education, child care, and much else. How will the federal government pay for it all? It seems no one really knows, in part because the dreary and unglamorous work of writing and following a budget plan has been all but abandoned in recent years. That needs to change for rational self-government to be sustained. Both parties long ago discarded orderly processes for setting tax and spending priorities to avoid inconvenient questions. Polarization has pushed the focus toward ideological ambitions, no matter the fiscal consequences. For Republicans, that has meant tax cuts without spending restraint. For Democrats, it has meant more domestic spending without the tax base to pay for it. The result is a fiscal deterioration without historical precedent. According to the Congressional Budget Office, the federal government is on track to accumulate debt surpassing 200 percent of GDP in three decades, not including the $1.9 trillion borrowed for the most recent COVID-19 response bill. If Congress approves yet more unfinanced spending this year, which is a possibility and is being actively pushed by many Democrats in Congress, the debt buildup will accelerate still further.

Federal Debt as a Percentage of Gross Domestic Product

(CBO) An important purpose of the federal budget process is to ensure individual spending and tax decisions are made with an understanding of their cumulative effects. A trillion here and there does indeed add up to real money. Before approving any of it, it is best to know how all of it will be financed or, if it won’t be, how much additional burden will be pushed onto future generations of Americans. The pandemic emergency is no longer a valid excuse for setting aside normal budgetary procedures. The Federal Reserve and other forecasters expect a rapid recovery in the second half of 2021, as vaccines allow resumption of more economic activity. Further, Congress has already approved nearly $6 trillion in emergency support measures over the past year; the case for going still further with more debt-financed spending is now very weak.

The Biden administration released a portion of the president’s first budget on April 9, and is said to be prepping a full budget, including tax and entitlement spending policies, for release at the end of May, or perhaps in early June. That will be roughly four months past the date specified in law for submission of the president’s plan, and later than the submissions from recent first-year presidents (For instance, President Obama submitted an outline of his full budget plan on February 26, 2009 and submitted a complete budget in early May 2009.) Yes, the Biden administration had many later-than-usual confirmations because of the disruptive transition between administrations, and yes, the pandemic and the vaccine rollout have quite rightly been the top priorities. Even so, the Biden administration did find the time to assemble and announce its multi-trillion-dollar plans for infrastructure and other social welfare programs without yet providing the full budgetary context within which they will be considered. Meanwhile, in Congress, Democrats have been contemplating a procedural novelty to avoid voting on a full budget. The plan involves passing an amendment to the shell budget resolution passed earlier this year authorizing another round of budget reconciliation legislation (budget reconciliation bills avoid Senate filibusters and thus can be approved with simple majorities). Perceptions here are important. Many Democrats do not want to vote on a budget resolution that is seen as representing their full fiscal plan because it might meet with disapproval among voters. In a complete and transparent budget, the administration’s push for several trillion dollars in tax and spending increases, along with historic levels of government borrowing, would be scrutinized. Many House and Senate Democrats would prefer to avoid that debate. That is understandable politically, but it comes with a real cost because approving a budget is a useful discipline, even when only one party is working on it. When a full budget must be presented for consideration, the focus is not just on new programs and new spending, but also on the existing and substantial base of pre-existing activity. It is the government’s responsibility to show the fiscal implications of adding new initiatives to old commitments, in terms of the totals for taxes, spending, deficits, and debt. Facing this prospect is often enough to screen out costly ideas with less merit. The current federal budget process is far from ideal. The executive and legislative branches operate under different rules, which means there is no guarantee they will agree on a fiscal plan. Over the past half-century, Congress has almost never met the deadline of October 1 for approving appropriations to keep the government operating. Government shutdowns, or serious threats of them, are now commonplace, and continuing resolutions—bills passed to extend an old, existing budget rather than approve a new one—are regular and expected occurrences. Further, current practice is too focused on hitting short-term deficit targets, which, ironically, are harder to change than the real problem, which is persistent and excessive borrowing over two and three decades. What would make a real difference for the nation’s fiscal stability are gradual adjustments to tax and entitlement programs that build over time, and thus narrow the long-term fiscal gap, but which won’t change budget totals significantly within the normal projection timeframe. Even with these limitations, however, following “regular order” would be far better than ignoring it. That might still happen. House Budget Committee Chairman John Yarmuth (D-Kentucky) has discussed proceeding with a real budget resolution in June, after the White House submits its plan. That would be a welcome development, as it would mean a renewed focused on a full federal fiscal plan and not just popular components. However, his thinking might still change as House and Senate leaders grapple with the difficulty of approving a budget resolution with their thin majorities. The federal government has been drifting away from the statutory budget process for many years. The results are not impressive. The government’s fiscal outlook has never been more adverse. Getting out the current hole will take a long time. The first step is to write a plan—a budget—and then follow it, no matter how unpleasant that task might be.