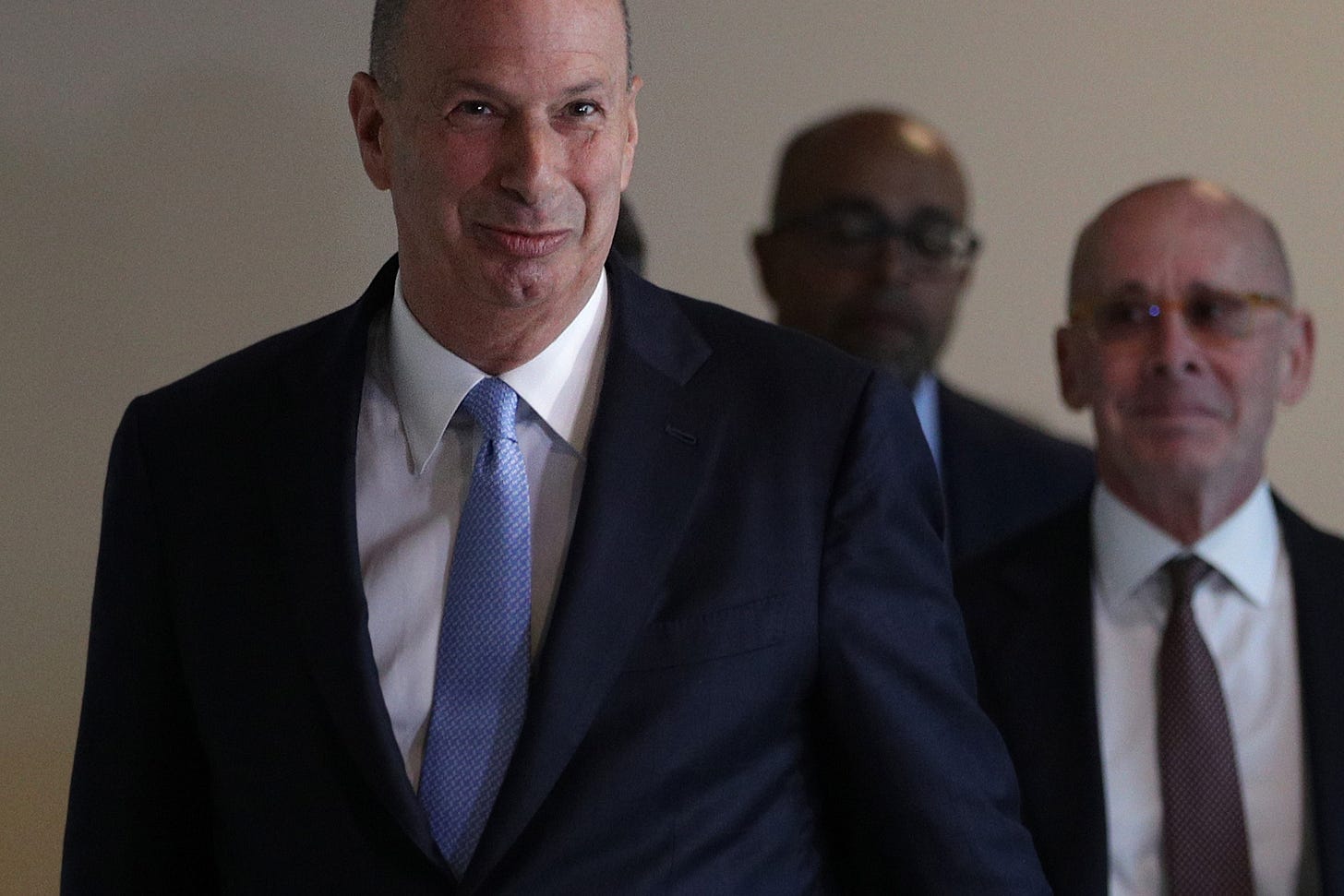

The Unbelievable Gordon Sondland

Parsing the contradictory testimony and timeline offered by Trump’s ambassador to the EU.

On October 17, the U.S. ambassador to the European Union, Gordon Sondland, testified in a private deposition before the House Intelligence Committee’s impeachment inquiry. Recently, the committee publicly released a transcript of his testimony. Included with the transcript was a supplementary “declaration” from Sondland dated November 4—after Sondland reviewed written testimony from acting ambassador William Taylor and National Security Council official Tim Morrison.

Sondland’s verbal and written testimony contradict one another—and clash with other established facts—in several ways. A close examination can provide a good preview for Sondland’s scheduled appearance this Wednesday before the committee in public session. It can also help shed some light on the overall timeline of the scandal at the heart of the impeachment proceedings.

Flipping on the quid pro quo. Sondland originally stated that he did not participate in any attempt to pressure Ukraine by withholding security assistance (Sondland testimony, p. 199). In the supplement, though, Sondland said he now remembers having told Andriy Yermak, an advisor to Ukraine’s president Volodymyr Zelensky, on September 1 that Ukraine would not receive the withheld security assistance without making “a public statement reopening the Burisma investigation” (Sondland supplement, p. 2), as President Trump had asked Zelensky to do in the infamous July 25 phone call.

But Sondland’s November 4 revision of the record did not fix his problems. Even with the inclusion of his supplemental testimony, Sondland’s original testimony still contains unamended statements that repeatedly misled Congress, omitted key events testified to by other officials, and appear to be false.

For example, Sondland claimed that after President Trump directed Sondland, special envoy Kurt Volker, and Energy Secretary Rick Perry to work on Ukraine policy with Rudy Giuliani on May 23, he did not perceive that the investigations Giuliani demanded were about Joe Biden. Sondland makes the following claims in his testimony:

He said that until late September, when he first read the partial transcript of Trump’s July 25 phone call, he did not know that he—along with Giuliani, Volker, and Perry—had been asking Ukraine to publicly commit to an investigation of Biden in return for a White House meeting (Sondland testimony, p. 119).

He said that, during a meeting between Trump administration officials and President Zelensky’s aides at the White House on July 10, he did not link a Zelensky White House meeting to investigations of Biden and 2016 (Sondland testimony, p. 223).

He said he was not aware of any conditions placed on the security assistance withheld by President Trump in July (Sondland testimony, p. 104), and did not participate in any scheme to pressure Ukraine using the security assistance (Sondland testimony, p. 36).

Let’s deal with each of these three trouble areas, one by one.

(1) What Sondland knew about the extortion scheme, and when he knew it. In his opening statement, Sondland said that he did not “recall” Giuliani discussing Biden or his son “with me” (Sondland testimony, p. 33). He also said that none of the summaries he received of President Trump’s July 25 call with President Zelensky included any mention of Biden (Sondland testimony, p. 28). And he said that he did not learn of Biden being part of what they were asking the Ukrainians to announce until Trump released the partial transcript of the July 25 call in late September (Sondland testimony, p. 119).

This is significant because Sondland claimed that in his conversations with Giuliani in August, Giuliani insisted that the Ukrainians announce investigations of 2016 and Burisma, but that Sondland did not know Hunter Biden was a Burisma board member. Sondland testified that he thought Burisma was merely “one of many examples of Ukrainian companies run by oligarchs and lacking the type of corporate governance structures found in Western companies” (Sondland testimony, p. 33). He portrayed himself as working reluctantly with Giuliani to assuage Trump’s concerns regarding Ukraine, and to secure a White House meeting for Zelensky, in furtherance of American interests in Ukraine.

Testimony delivered last Friday, November 15, by one of Ambassador Taylor’s aides in Kiev, David Holmes, contradicts Sondland’s claim. Holmes testified that while Sondland was in Kiev on July 26 for a meeting with Zelensky, Holmes overheard a phone call between Sondland and Trump wherein the president asked if Zelensky is “gonna do the investigation,” and Sondland replied that “he’s gonna do it” (Holmes opening statement, p. 8). Holmes testified that he asked Sondland, after the Trump call ended,

if it was true that the President did not give a shit about Ukraine. Ambassador Sondland agreed that the President did not give a shit about Ukraine. I asked why not, and Ambassador Sondland stated, the President only cares about “big stuff.” I noted that there was “big stuff” going on in Ukraine, like a war with Russia. And Ambassador Sondland replied that he meant “big stuff” that benefits the President, like the “Biden investigation” that Mr. Giuliani was pushing. [Holmes testimony, p. 25]

Sondland’s phone conversation with the president, as overheard by Holmes, and his statement to Holmes both directly contradict Sondland’s own timeline of events. Sondland testified that he was not aware until late September that the investigation’s target was Joe Biden. His July 26 conversation with Holmes indicates that was false.

Even more damning, Sondland claimed in his October testimony that “all the communication flowed through Rudy Giuliani,” and that he could “only speculate” that Trump was instructing Giuliani (Sondland testimony, p. 297). Holmes’s recollection of Sondland’s phone conversation shows that Sondland was directly involved in informing the president, and that Trump was actively asking whether Zelensky would open the investigations he sought. By July 26, the president had withheld a promised White House meeting for Zelensky, withheld security assistance for Ukraine, pressed Zelensky to open the investigations of Biden and 2016, and asked Sondland if Zelensky would indeed open the investigations.

In other words, it seems that Sondland lied to Congress about Trump’s knowledge and direct involvement in the extortion effort.

(2) What really happened at the July 10 meeting? Let’s return to Sondland’s claim, in his testimony, that, when he met with Ukrainian officials at the White House on July 10, he did not condition a Zelensky meeting with Trump at the White House on the Ukrainians investigating Biden and 2016 (Sondland testimony, p. 223). This is important because it is necessary to sustain his larger false timeline in which he and Giuliani et al. were supposedly just pressing Ukraine to focus on general anticorruption in July. If it turns out that he was indeed pressing Ukraine to investigate Biden on July 10, then he was acting improperly, even by his own words: “Inviting a foreign government to undertake investigations for the purpose of influencing an upcoming U.S. election would be wrong” (Sondland testimony, p. 36).

Sondland’s testimony, however, appears to be false. Lt. Col. Alexander Vindman—an Army officer currently detailed to the National Security Council staff—told the committee that at the July 10 meeting, Sondland had indeed spoken about the importance of Ukraine delivering investigations of Biden and 2016 if they wished to have a White House meeting with the president (Vindman testimony, pp. 17-18). And Fiona Hill—who was, until August, also a National Security Council staffer—corroborated this account of the July 10 meeting:

Ambassador Sondland, in front of the Ukrainians, as I came in, was talking about how he had an agreement with Chief of Staff Mulvaney for a meeting [of President Trump] with the Ukrainians if they were going to go forward with investigations. [Hill testimony, p. 69]

Vindman and Hill both say they told Sondland that his actions were inappropriate, which Sondland also testified did not occur. Assuming Vindman’s and Hill’s accounts are correct, that means that Sondland was pressing the Ukrainians to open investigations into the Bidens in exchange for a White House meeting as early as July 10, and that Zelensky was likely aware of the demand ahead of the July 25 phone call with Trump.

(3) Covering up the withholding of aid. Sondland insisted in his deposition that he was unaware of any conditions placed on the delivery of security assistance (Sondland testimony, p. 104) and that he did not participate in any schemes to use the security assistance to pressure Ukraine, which he says would be illicit: “Withholding foreign aid in order to pressure a foreign government to take such steps [i.e., undertake a partisan investigation] would be wrong” (Sondland testimony, p. 36).

Sondland’s supplemental written testimony partially cleaned up this conflict in the record. He says he now remembers that he did, in fact, participate in a scheme to pressure Ukraine using the security assistance. His memory having been jogged, Sondland now says that on September 1, he told Yermak that Ukraine would not receive the security assistance without announcing investigations (Sondland supplement, p. 2).

That is a significant admission. Despite Republican claims that there was no quid pro quo, Sondland has conceded that he told the Ukrainians that they would not receive a White House meeting or security assistance without announcing investigations. However, even in his supplemental testimony, Sondland has still maintained that he did not receive any explanation for why the aid was withheld, so he “presumed” that the suspension of the aid “had become linked to the proposed anti-corruption statement”—that is, the Ukrainian announcement of investigations.

This is a rather comical statement: Sondland is saying that he told Ukrainian officials that their country would not receive security assistance without announcing an investigation of the president’s political opponent and 2016 conspiracy theory, and that he did that based on absolutely no direction from the president. It is important for Trump that Sondland hold to that line, though. By saying he “did not know . . . when, why, or by whom the aid was suspended,” and that he merely presumed that the reason was to pressure Ukraine to announce investigations, Sondland insulates Trump from the extortion message (Sondland supplement, p. 2).

This is consistent with Sondland’s description of a September call he had with Trump. On September 9, Taylor sent a text message to Sondland: “As I said on the phone, I think it’s crazy to withhold security assistance for help with a political campaign.” In Sondland’s telling, he then called Trump to find out why the aid was being withheld. Sondland testified that he asked Trump what he wanted, and that Trump said “I want nothing. I want no quid pro quo” (Sondland testimony, pp. 104-106). Five hours after Taylor’s text, Sondland responded with what reads like a scripted message for the record:

Bill, I believe you are incorrect about President Trump’s intentions. The President has been crystal clear no quid pro quo’s of any kind. The President is trying to evaluate whether Ukraine is truly going to adopt the transparency and reforms that President Zelensky promised during his campaign I suggest we stop the back and forth by text If you still have concerns I recommend you give Lisa Kenna or S a call to discuss them directly. Thanks.

Now, let’s first note how absurd what Sondland says he did is. According to Sondland, on September 1, he knew that the security assistance had been held up, but did not know why. So, instead of calling the president to clarify the reason, he instead just “presumed” the president held it up to pressure the Ukrainians to announce investigations. Then, supposedly based on nothing more than that presumption, he told Yermak that Ukraine would not receive the security assistance without an announcement. But after Taylor raised his concerns about the linkage more than a week later, Sondland then decided to call the president to ask why he withheld the aid. One might think that Sondland would want that clarification before telling the Ukrainians that they would not receive the security assistance without an investigation.

It gets worse. This call, and Sondland’s subsequent message to Taylor, look different in light of testimony from Taylor and the NSC official Morrison. Morrison says that Sondland told him on September 7 about a conversation in which the president said that there was “not a quid pro quo” and that Zelensky “should want to go to a microphone and announce personally” the investigations himself (Morrison testimony, p. 144-145). Sondland told Taylor that, on the call, Trump insisted that Zelensky had to “clear things up and do it in public” (Taylor opening statement, p. 12).

In other words, in a call just a couple of days before Taylor’s alarmed text message, Trump had laid out the demand for Sondland: After withholding a White House meeting in return for investigations, and now withholding security assistance, Trump insisted that Zelensky personally announce the investigations. Then, after Taylor’s text, Sondland called Trump a second time in two days, and sent a reply to Taylor clearly meant to make a record that Trump did not want a quid pro quo. Sondland did not need to clarify with Trump why he had withheld the assistance; he had spoken to him just a couple days earlier. But he did need to figure out how to address Taylor creating a record of the linkage of investigations to security assistance, and he called the president to discuss.

After speaking again with Trump, Sondland sent his message to Taylor claiming that the president had been “crystal clear” that there is no quid pro quo—omitting, of course, that Trump had laid out his quid pro quo terms in a call just days earlier. Like Sondland’s claim that all communication flowed through Giuliani, Sondland’s message to Taylor and his testimony about his calls with the president appear to be an attempt to hide that the president directed the extortion scheme personally.

Which way will Sondland go? In reviewing the timeline of events and testimony, a clear story emerges. In May, Trump directed his officials to work with Giuliani, whose interest in pushing Ukraine to investigate Biden and 2016 was widely reported at the time. During the summer, Sondland and Volker pressed Ukraine to announce those investigations in return for a White House meeting, something desperately sought by Zelensky. Trump froze security assistance appropriated by Congress for Ukraine with no explanation internally. On the July 25 call, Trump himself asked Zelensky for those investigations in response to Zelensky saying they are prepared to purchase Javelin anti-tank missiles. After the call, Sondland and Volker continued to press Ukraine to announce the investigations, while the president sought at least one update from Sondland regarding whether Zelensky would investigate Biden.

Finally, after the Ukrainians had still not made a public announcement, Sondland—perhaps at the president’s instruction—linked the withheld security assistance to the investigations, too. Sondland, Volker, and Perry worked with Giuliani in a scheme to pressure Ukraine to deliver investigations helpful to the president’s 2020 campaign, using the U.S. support desperately needed by Ukraine as leverage, and did so both with the president’s direction and explicit involvement. Sondland misled Congress about his involvement in the scheme, and about the president’s own knowledge and participation.

Sondland has already lied to Congress and the American people about both the president’s actions and Sondland’s own involvement. Will he continue to try to protect the president, despite it being amply clear he has lied? Will he try to protect himself, by pleading the Fifth? Or will he do the right thing, and tell us the truth? His reputation and integrity, such as they are, hang in the balance.