The Urban Workforce Shakeup

Talent migration, COVID, and the end to winner-take-all urbanism.

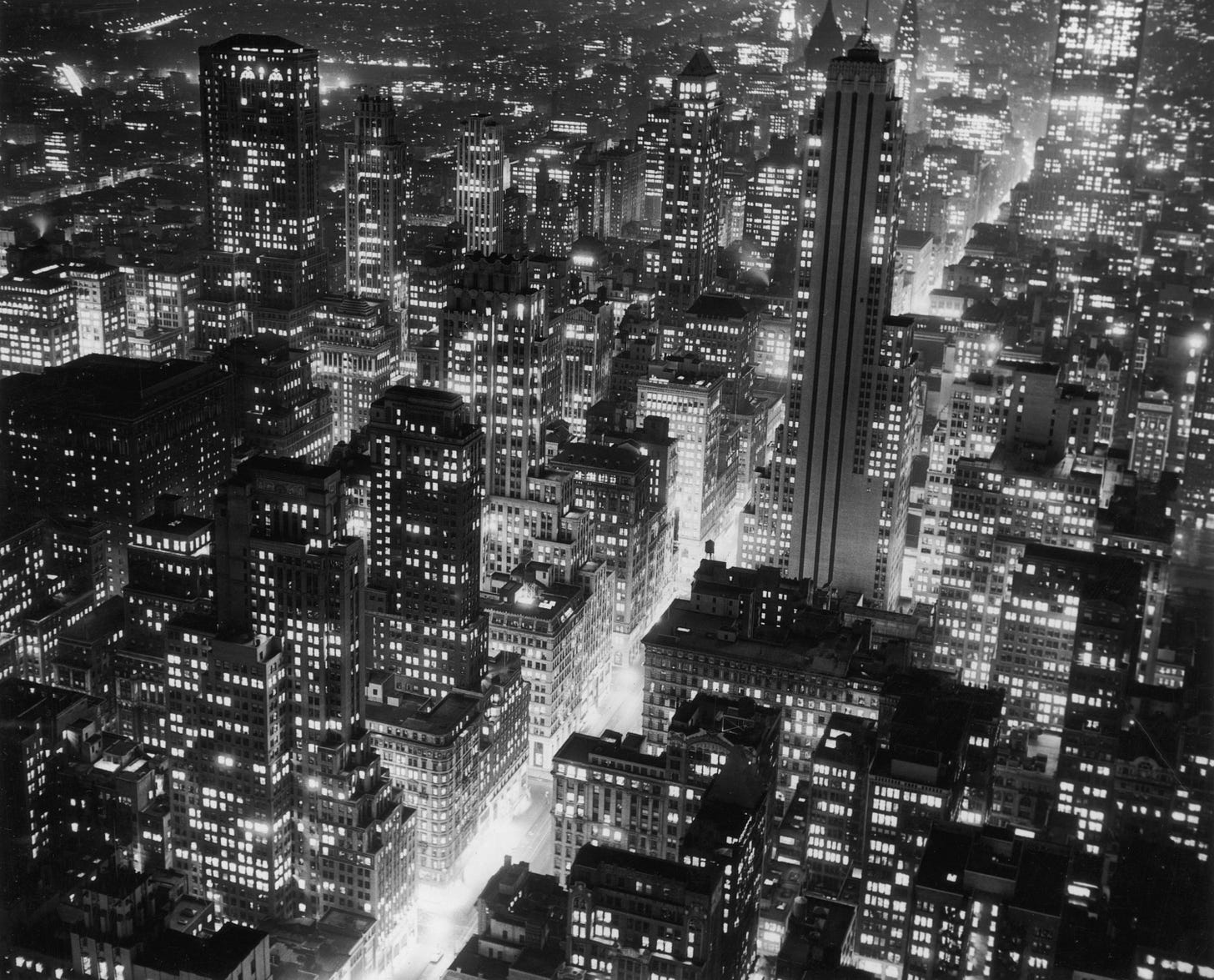

For decades, America’s big coastal cities have been magnets for the nation’s best-educated and most highly skilled workers seeking not just good jobs but the amenities and diversity that those cities afford. Those cities attract “citizens of the world” working in occupations integrated with an increasingly globalized economy. As has been widely noted in the past few years, the social and political consequences of these “agglomeration effects”—the self-compounding ability of big cities to attract and deploy talent—has not been wholly positive, sparking socioeconomic resentment between the urban centers and the interior of the country.

Scholars and commentators on this phenomenon, like Richard Florida, described this talent concentration as a keystone of “winner-take-all-urbanism.” This is where the smart, wealthy, and happy become smarter, wealthier, and happier over time, while smaller cities, towns, and rural areas assume supportive roles in the national economic story or atrophy entirely. Imbalances also built up in our major cities, with the supply for housing and other services struggling to keep pace with demand, leading to rapidly escalating housing costs.

The COVID-19 pandemic laid bare the vulnerabilities that companies expose themselves to by concentrating their workforces in dense urban centers. Starting about a year ago, what once looked immutable suddenly began to appear unsustainable.

New data from Emsi, a labor market analytics firm based in Moscow, Idaho, suggests that we hit “peak big city” several years ago. (The story of the company itself is illustrative. Who would have thought thirty years ago that Moscow, Idaho would become the home of a large analytics firm servicing companies and governments around the country in identifying emerging regional labor-market trends?) Emsi’s Talent Scorecard, an annual study that tracks talent migration, shows that mid-sized counties make up over half of the top 100 for talent flow while big urban centers have dropped far down the list.

In fact, eight of the nation’s most populated counties fall in the bottom third of the rankings. Maricopa and Riverside counties are the only two large counties to crack the top 10, a complete reversal from trends we witnessed roughly a decade ago.

There are several key drivers of these talent shifts. The first is the relocation of businesses. More and more firms are opting for states and localities with more “business friendly policies” (lighter taxation and regulation and, sometimes, more generous subsidies) and lower costs of living. Workers are happy to follow these businesses to escape the high-cost-of-living cities with out-of-control rents. Then there is the rise of remote work, a trend accelerated by the pandemic. Emsi found that job postings for remote positions were up 154 percent in November 2020 compared to their pre-COVID average—speeding the movement of talent that no longer need to be close to the office to obtain and keep a good job.

There also appears to be a reverse agglomeration effect with a self-reinforcing cycle creating regional hotspots across the country. This is driven by firms clustering in new locations such as Austin and Atlanta, and by the remote workforce as it spreads out across the country, allowing a segment of the workforce to create bespoke lifestyles in communities distant from company offices. In many ways, this is a winning combination for businesses, their workforces, and the country as a whole making it possible for smaller cities and rural areas to attract companies based on lower costs and higher quality of life. Just as Emsi has prospered despite its location away from coastal cities, other fast-growing companies, especially in knowledge sectors of the economy, may decide that locating on what used to be called the ‘information superhighway’ is preferable to being near an actual one.

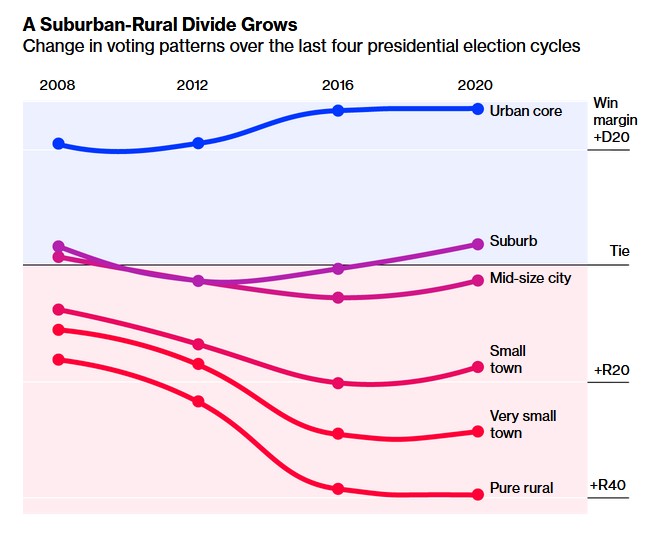

The implications of the talent migration trend for American society and politics is potentially large. When people move, they take their values and beliefs with them, changing the social and political complexions of the areas they move to. As we saw in the recent presidential election, traditionally “red” states like Arizona and Georgia are turning purple, a result, in part, of Southern California companies and workers moving to places like Maricopa County and Midwest and Northeast firms to suburban Atlanta. Similar trends are occurring across the country, with prosperous suburban and even exurban areas shifting toward Democrats, at least at the presidential level, driven by migrations that started as economic and lifestyle choices. Who knows? Over time, we might even see more immigrant-heavy cities begin to have less of a Democratic tilt, as rising entrepreneurial classes increase their influence. Something like this appears to have happened already in places like Philadelphia, Detroit, and elsewhere last November, the effect of further GOP agitation against minority voters notwithstanding.

Whether or not talent continues to move towards the nation’s second cities and places further flung is yet to be seen, but it is clear that the nation’s big superstar cities aren’t the clear-cut destination of choice anymore. This has longer term implications not just for talent migration, but for economic development, the nation’s politics, and the look and shape of cities whose lifeblood is the businesses and workforces that choose to call them home.