Third Parties, Political Purity, and “Throwing Away Your Votes”

Lessons for 2020 from the election of 1844.

In the American political system, third parties have typically attracted candidates and voters on the fringes or in exile. It is when third parties move toward the mainstream and start to attract significant numbers of voters that they begin to get the attention of the press and become annoyances for the two major parties. Consider, for example, Ross Perot’s bid for the presidency in 1992. His 18.9 percent of the popular vote—the biggest share won by any third-party candidate since Teddy Roosevelt’s 1912 Bull Moose campaign—undoubtedly played a role in George H.W. Bush’s loss to Bill Clinton.

In the 2016 election, the 6 percent of the voters who cast their ballots for someone other than the two major-party candidates may have had any number of motivations. Some probably protested against Trump by voting third party with the expectation of a Clinton victory, while others probably condemned both candidates as equally bad. Still other voters would have genuinely preferred a third-party candidate. While not huge, third-party candidates’ total share of the vote was electorally significant: The Libertarian party candidate, Gary Johnson, won a bit over 3 percent of the national popular vote, which was greater than the national difference between Trump and Clinton. In the key battleground state of Pennsylvania, the vote for Johnson was triple the size of Trump’s margin of victory; in Wisconsin, Johnson’s vote was quadruple Trump’s margin; in Michigan, Johnson’s vote was sixteen times Trump’s margin.

The phenomena that can drive candidates and voters to third parties—polarization, political homelessness, and a desire for a kind of electoral purity—are not new in American politics. To understand the dynamic that can give rise to third-party voting, sway an election, and have lasting historical consequences, it is worth examining the election of 1844 between the Democrat James K. Polk, the Whig Henry Clay, and the Liberty party nominee James G. Birney.

Following the rise of Andrew Jackson to the presidency and the birth of the Democratic party, critics and defectors allied to form the Whig party. It began as an oppositional coalition but under the leadership of the Kentuckian Henry Clay in 1833, the Whigs soon formed their own political identity. They called for the chartering of banks and the use of paper money (both of which Jackson had opposed) and the subsidization of internal improvements. While both parties had anti-slavery wings and both included slaveholders among their leaders, by the middle of the nineteenth century, the Whigs had garnered the reputation as the party more hostile to slavery.

Yet the Whigs were hardly a united front against slavery, and often the issue served as a wedge that split the party’s Northern and Southern factions. As time went on, some of the “Conscience Whigs”—those who opposed slavery—found it more difficult to abide the party’s pro-slavery members. Given the state of the Democratic and Whig parties, abolitionists and anti-slavery advocates debated how best to proceed toward bringing about slavery’s ultimate destruction. William Lloyd Garrison and his radical abolitionists, while politically outspoken, eschewed participating in party politics, arguing that doing so would mean compromising their values and prolonging the enslavement of black Americans. Others, however, viewed working within the political system as the most realistic way to bring about lasting change—and thus was born the Liberty party.

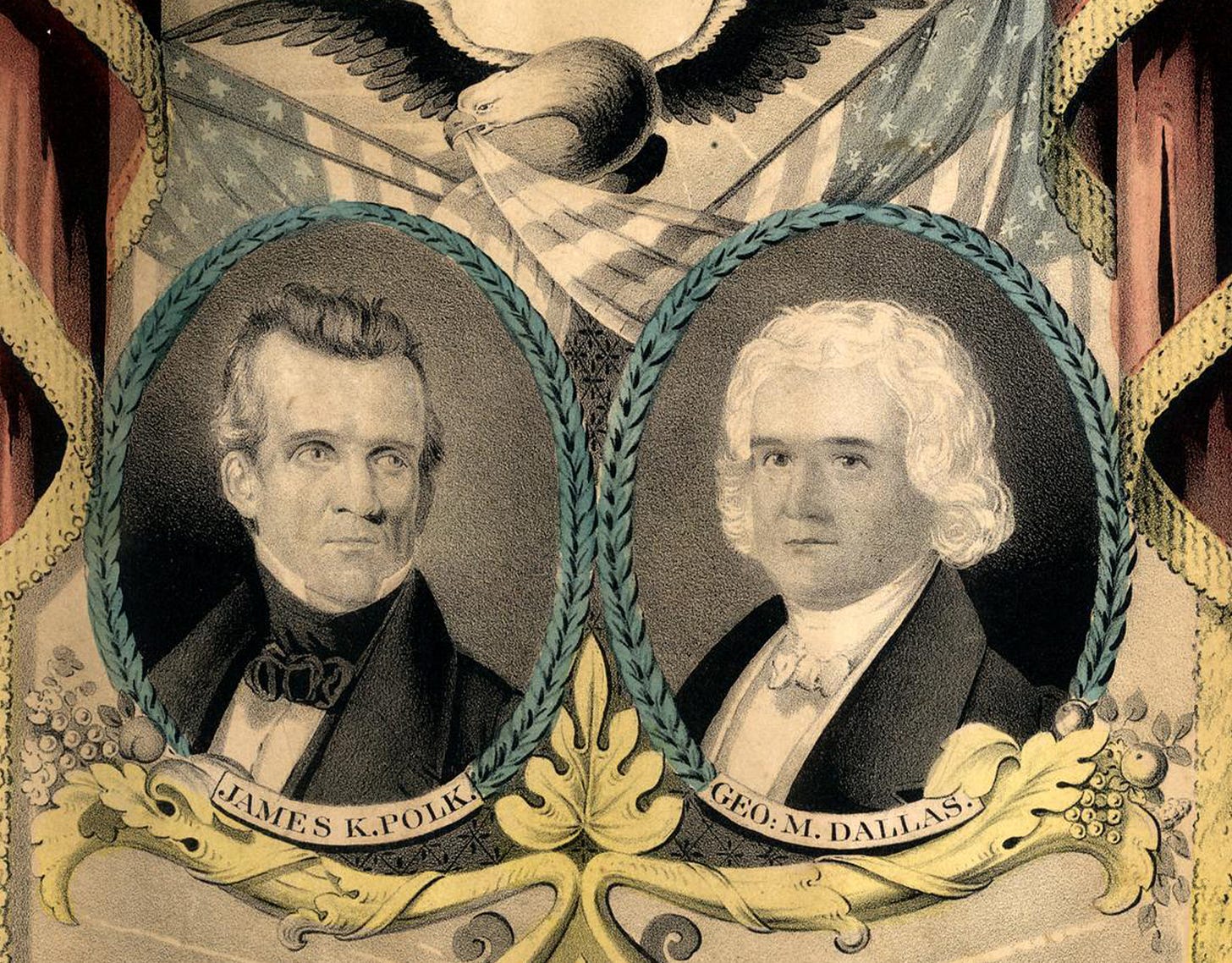

As the 1844 election approached, the Democrats were keen to retake the White House. The last Democratic presidency, the one term of Jackson’s successor Martin Van Buren, had been defined by the economic hardship that followed the Panic of 1837. The Whigs’ victory in 1840 resulted in the short-lived presidency of William Henry Harrison and the contentious presidency of John Tyler. As Whigs and Democrats prepared for the 1844 contest, it became clear that the annexation of Texas—and with it the expansion of slavery—would dominate political discourse. While Van Buren had been angling to position himself as a comeback candidate for his party, after some behind-the-scenes political fixing and a series of convention battles the Democrats instead selected as their champion former House speaker James K. Polk of Tennessee. Polk was a political figure of little importance—the Whigs ridiculed him with the slogan “Who is James K. Polk?”—but he was a protégé of Jackson, a prominent slaveholder, and a steadfast expansionist. He was trumpeted as Young Hickory to Jackson’s Old Hickory. Such credentials made him an ideal choice for most of the South.

Meanwhile, Henry Clay—former senator, former speaker of the House, former secretary of state—was the undisputed leader of the Whig party and its candidate for the presidency. With Clay opposing the annexation of Texas, believing such a move would spark a war with Mexico and increase the Southern slave power’s influence on politics, the Northern states lined up behind the Whigs. But it was also in these Northern states that Clay faced a strong backlash from abolitionist activists and the anti-slavery Liberty party. Even though Clay’s views on Texas as well as the other territories largely gelled with those of the Liberty party, Clay and the Whigs came under intense criticism.

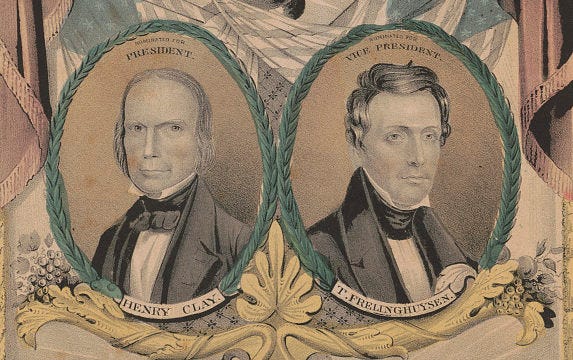

Detail from another Nathaniel Currier banner, this time for the 1844 Whig party presidential ticket: Henry Clay (left) and Theodore M. Frelinghuysen. (Library of Congress)

The presidential candidate of the small Liberty party in 1840 and again in 1844 was James G. Birney, a former Kentuckian who had moved north to Ohio. Birney, who had previously campaigned for Clay and gotten along well with him, had formerly agreed with Clay that the most effective way to end slavery was colonization—that is, a movement to “voluntarily” relocate blacks from America to Africa. But over time the men grew apart, with Birney coming to embrace the immediate abolition of slavery. Pro-slavery Democrats delighted at the situation and sought to further divide voters between the Whigs and the Liberty party by reprinting excerpts from Clay’s speeches where he had criticized abolitionists and defended slavery. Meanwhile, in the South, Democrats galvanized voters with records of Clay’s anti-slavery sentiments. Clay, always the great compromiser, tried to appease both Northern and Southern interests but slavery would prove non-negotiable for some voters.

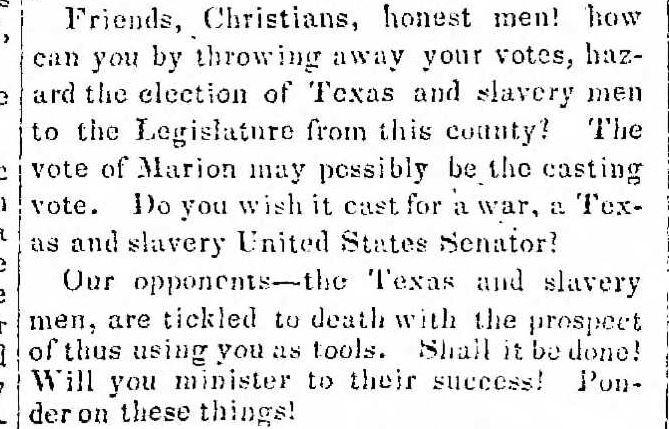

What is striking is how aware of the situation Whigs were. A pro-Whig newspaper, the Indiana State Journal, pleaded with its readers on August 3, 1844 that supporting the Liberty party would be “throwing away your votes,” while “our opponents . . . are tickled to death with the prospect of thus using you as tools”:

Other abolitionist outlets, the Worcester Spy and Boston Atlas, printed an even blunter editorial around the time of the midterm elections in 1842: “Let it be understood, that every abolitionist who, by refusing to vote as a Whig, adds to the strength of the Southern party, does, in effect, vote for the maintenance of slavery.”

But such sentiments did not move the Liberty men. Abel W. Brown, a Baptist preacher and anti-slavery publisher, as well as a member of the Liberty party, denounced Clay as a “Sabbath breaker, Swearer, Gambler, Duelist, Thief, Robber, Adulterer, Man-stealer, Slaveholder, &c.” According to Brown, Clay “buys and sells our Lord Jesus Christ, in the persons of his oppressed children”—that is, through his enslavement of black Americans.

In the end, Polk narrowly won the presidency. Though he scored 170 Electoral College votes to Clay’s 105, on the ground the results were nail-bitingly close. In Michigan, Polk beat Clay by just 3,362 votes. Had Michigan’s 3,639 Birney voters instead gone for Clay, he would have won the state. In New York, Polk won by a mere 5,106 votes out of nearly half a million cast. If even a third of the 15,812 New Yorkers who voted for Birney had held their noses and voted for Clay, the state’s 36 Electoral College votes would have been his and he would have been president. As one anti-slavery Whig, Abraham Lincoln, put it in a letter to a friend the next year, “If the whig abolitionists of New York had voted with us last fall, Mr. Clay would now be president, whig principles in the ascendent, and Texas not annexed; whereas by the division [of the Whig and Liberty parties], all that either had at stake in the contest, was lost.”

Their defiance of slavery had determined the outcome of the election.

With this in mind, how should we view the legacies of the Liberty party voters? Given the later birth of the anti-slavery Republican party, did the purist Liberty party lose the battle of 1844 only to win the war against slavery in the long run? Or did the Liberty party delay slavery’s demise by unintentionally aiding the victory of Polk? Would Clay have worked to help end slavery, a practice he claimed he disapproved of? Or would have he continued to strike deals with the South, revealing himself to be unable or unwilling to fight the power of the slave states? These types of counterfactual questions are impossible to answer, but they should offer us pause in thinking about our own moment.

The moral stakes and political circumstances of 1844—when human bondage was being debated and the very enslaved people on whose fate the election centered were deprived of the franchise—were very different from those of today. But by looking just at the dynamic of third-party voting in the context of a polarized electorate, we might still draw some lessons that are relevant to 2020. A few months ago, when the Democratic primaries were at their most heated, it seemed possible that disappointed Bernie Sanders supporters might refuse to vote for the more moderate Joe Biden, but recent polling suggests that is unlikely to be a significant factor in the general election. Even so, it seems the alliance between the progressive and centrist wings of the Democratic party are fragile.

As for third-party candidates, this year’s Libertarian party nominee, Jo Jorgensen, who has never won an election or held political office, seems unlikely to draw the kind of following that Gary Johnson, a former governor, attracted from protest voters in 2016. Conservatives who find themselves unwilling to vote for Trump will have to ask themselves what would be gained by voting for Jorgensen (or some other third-party candidate) and what will be at stake?

Trump’s victory in 2016 was result of a perfect storm of political events and ultimately a slim Electoral College win. Yet in the time that Trump has been president, he has thoroughly rebranded the Republican party, stripping out every aspect of compassionate conservatism and replacing it with “owning the libs” and national populism. Conservatives longing for the exorcism of Trumpism from the GOP may be waiting in vain. While the polls suggest that Trump’s re-election bid is likely to fail, even a narrow defeat could cement the Trumpian transformation of the GOP for decades to come. Yet can pro-life, limited-government-advocating, Second Amendment-supporting conservatives really make any kind of long-term home for themselves in the Democratic party? Given the dwindling influence within the party of the “Blue Dogs” and the “New Democrats,” this seems unlikely.

Politics is always a balancing act between strategy and sacrifice, calculation and compromise. Voting for Jorgensen or some other third-party candidate may seem tempting, or may even seem to have a certain logic to it. Like the Conscience Whigs before them, some Never Trump Republicans may feel themselves to be in a bind. Do they refuse to join the Biden coalition in the hopes of winning the longer war for the soul of conservatism? Do they ease their consciences by writing in Mitt Romney while effectively casting aside their votes? Do libertarians and other voters tempted by third-party candidates hold on to their purist convictions while knowing victory is impossible? Or do they compromise their principles to stop a man whom they have denounced as a threat to the very foundations of the republic? As frustrating as it may be, successful American politicking has always been coalitional.