This Guy Is the Reason Bill Cosby Is Out of Prison

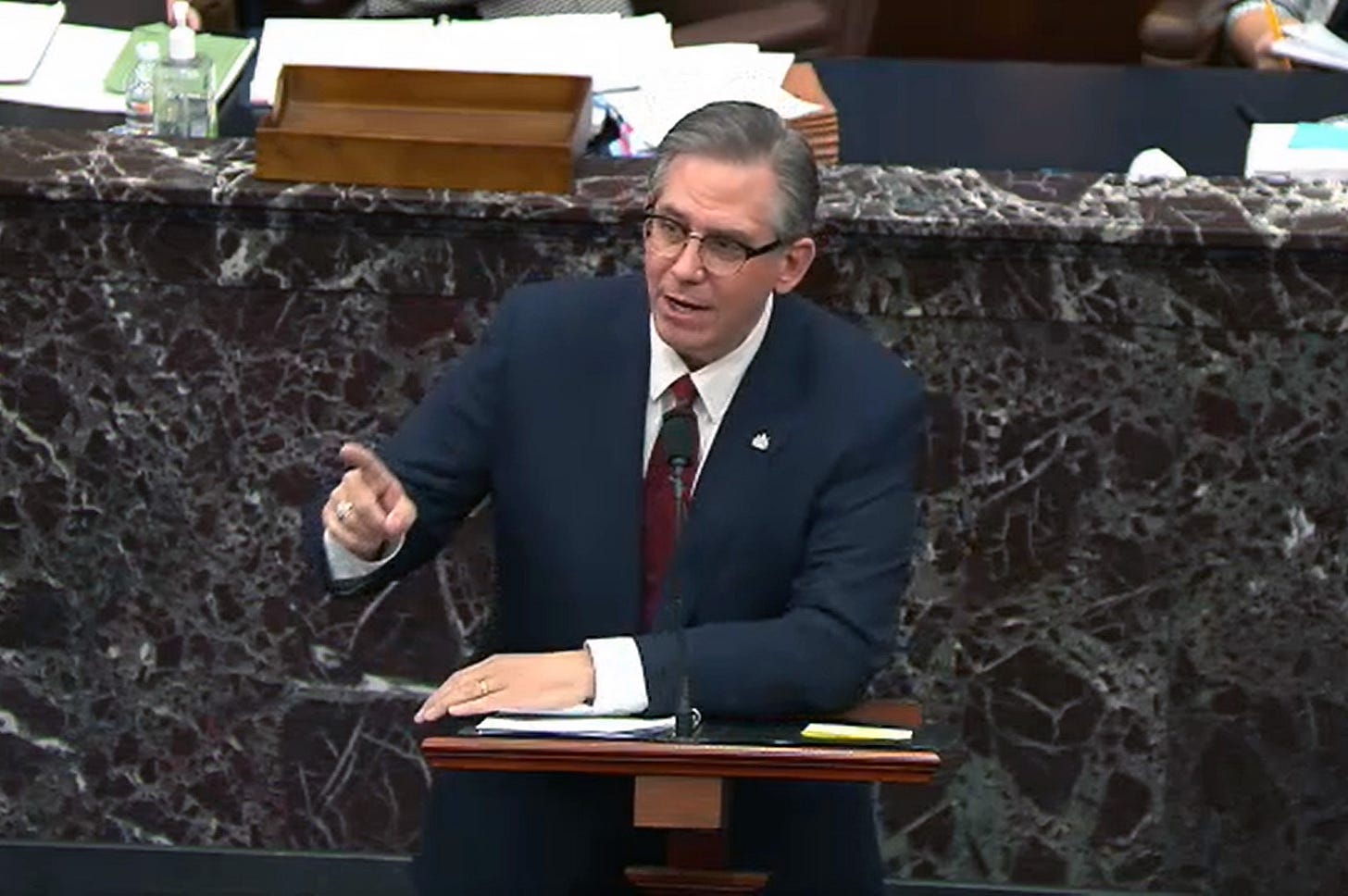

The same lawyer who bumbled through Trump’s impeachment defense.

The Supreme Court of Pennsylvania’s decision yesterday reversing Bill Cosby’s criminal conviction for aggravated assault has been described as the result of a prior “non-prosecution agreement” with the Montgomery County, Pa. district attorney’s office. This is not entirely accurate.

In 2005, that office issued a press statement announcing that it was declining to prosecute Cosby for his 2004 sexual assault of Andrea Constand at his residence, citing perceived flaws in the available evidence. Cosby later provided incriminating testimony in Constand’s civil suit, which was used in the commonwealth’s subsequent criminal trial. The Pennsylvania high court construed the ambiguity regarding the existence of a non-prosecution agreement in Cosby’s favor, holding that he was misled—in violation of his constitutional rights to due process and Fifth Amendment protection against self-incrimination—into believing that his civil deposition testimony couldn’t be used against him criminally.

The fault for this debacle lies at the feet of Cosby’s lawyers, as well as the Montgomery County district attorney in charge at the time: Bruce Castor, who later defended Donald J. Trump in his second impeachment trial. It was Castor’s missteps—not any problems with the evidence and its power convincing a jury of Cosby’s guilt—that produced Cosby’s freedom.

It will surprise no one to hear that Trump hired a sloppy lawyer to champion one of his many dubious causes.

The Fifth Amendment privilege against self-incrimination provides that no person “shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself.” To secure testimony from key witnesses who have refused to potentially incriminate themselves, prosecutors routinely enter into formal immunity agreements of two types. As the Justice Department describes it, “transactional immunity protects the witness from prosecution for the offense or offenses involved, whereas use immunity only protects the witness against the government’s use of his or her immunized testimony in a prosecution of the witness—except in a subsequent prosecution for perjury or giving a false statement.” (Emphasis added.) Castor brokered neither.

As the six-member majority of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court explained, the trial court held an evidentiary hearing on whether Castor’s press release—a press release!—was binding on his successor in the D.A.’s office, thereby insulating Cosby from a future prosecution. Castor himself testified: “The Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution states that a person may not be compelled to give evidence against themselves. . . . So the way you remove that from a witness is—if you want to, and what I did in this case—is I made the decision as the sovereign that Mr. Cosby would not be prosecuted no matter what.”

The “sovereign” Castor’s press release—the only document memorializing the purported non-prosecution agreement—stated:

The District Attorney concludes that a conviction under the circumstances of this case would be unattainable. As such, District Attorney Castor declines to authorize the filing of criminal charges in connection with this matter.

Yet the press release adds that “District Attorney Castor cautions all parties to this matter that he will reconsider this decision should the need arise.” Castor did not communicate with Constand or her lawyers about this decision, and later, Cosby’s lawyers did not direct their client to invoke his Fifth Amendment rights during any of his four depositions in Constand’s civil case, which ultimately produced a $3.38 million settlement. Rather, Cosby freely testified that he had “a romantic interest in Constand as soon as he met her,” that he had sex with her three times, and that he gave her pills “to help her relax.” Castor’s successor, Risa Vetri Ferman, used that testimony to prosecute and convict Cosby subsequently.

When Castor learned of Ferman’s plan to prosecute Cosby, he sent her an email asserting that he had “intentionally and specifically bound the Commonwealth that there would be no state prosecution of Cosby.” Vetri responded that his email was the first she’d heard of any such binding agreement, save for the press release, and went forward with the prosecution.

This is incredibly sloppy lawyering on the part of Castor—not to mention Cosby’s counsel. As the lower court noted, Castor testified that Cosby’s lawyer “never agreed to anything in exchange for Mr. Cosby not being prosecuted,” that “he could not recall any other case where he made this type of binding legal analysis in Montgomery County,” that the press release specifically cautioned that he could “reconsider” the decision, and that “the possibility of a civil suit was never discussed with anyone from the Commonwealth or anyone representing [Cosby] during the criminal investigation” under Castor.

Nor did the lower court find any legal authority for Castor’s “proposition that a prosecutor may unilaterally confer transactional immunity through a declaration as the sovereign.” Instead, “such immunity can be conferred only upon strict compliance with Pennsylvania’s immunity statute, which is codified at 42 Pa.C.S. § 5947,” and which requires the court’s express permission. None of this occurred. Worse, Castor waffled on whether he intended to grant transactional immunity or use immunity, undermining the notion that a binding agreement was reached.

Fast-forward to Trump’s second impeachment trial, a scant five months ago, in which Castor was widely ridiculed for his rambling, factually inaccurate, and ad libbed opening statement. Even Alan Dershowitz (who was criticized for his own spurious argument during the first impeachment that presidents cannot be impeached for election wrongdoing if they believe their own re-election is in the public’s interest) told the right-wing outlet Newsmax: “There is no argument. I have no idea what he is doing.” By way of cringeworthy example: Castor admitted that he changed his opening speech because the House managers’ presentation was so “well done”; offered that “we are generally a social people” who “enjoy being around one another”; clarified that “senators of the United States, they’re not ordinary people”; and incoherently noted that “we still know what records are, right—on the thing you put the needle down on and you play it.”

Despite Castor’s ineptitude, Trump, like Cosby, was ultimately let off the hook for reasons that had nothing to do with actual guilt regarding the bloody Jan. 6 insurrection that left five people dead. The fact that American courts are still operating to hold officeholders like Castor accountable for their lousy performance offers a measure of comfort for those who fear the demise of the rule of law in the United States, although a flickering one.