Thomas Jefferson’s Not-So-Peculiar Mind

What the third president’s unorthodox cut-and-paste project can teach us about our longings and our politics.

The Jefferson Bible A Biography by Peter Manseau Princeton, 221 pp., $24.95

There’s a strange turn of phrase in the middle of George Washington’s 1796 Farewell Address. After announcing his decision to retire from the presidency, Washington offers his fellow citizens advice on how to protect the young republic from cultural factionalism and political division. One safeguard was the importance of religious institutions. “And let us with caution indulge the supposition, that morality can be maintained without religion,” Washington warns. “Whatever may be conceded to the influence of refined education on minds of peculiar structure, reason and experience both forbid us to expect that national morality can prevail in exclusion of religious principle” (emphasis added).

Washington’s views on the interplay of politics and religion have occupied thousands of pages, but few include a serious examination of what exactly he meant in his gesture toward owners of unconventional cerebra. Those who take up the question speculate that he may have had his former secretary of state in mind. By the 1790s, Thomas Jefferson’s unorthodox religious views were well known. Not only had he railed against organized religion in the Notes on the State of Virginia, he had also served as the primary author of Virginia’s seminal Statute for Religious Freedom, which eliminated state-sponsored churches as a defense of “civil rights[, which] have no dependance on our religious opinions, any more than on our opinions in physics or geometry.”

Like Jefferson, Washington—whose own religious beliefs were rather idiosyncratic—was a strong proponent of religious pluralism. But one wonders what he would have thought of another Jeffersonian religious project he never lived to see. For during Jefferson’s first presidential term in office, he embarked on a quiet crusade to save no less than Jesus Christ himself from centuries of superstitious tyranny that obfuscated his role as one of world’s greatest philosophers. And he would do so by literally cutting Jesus out of his scriptural cage.

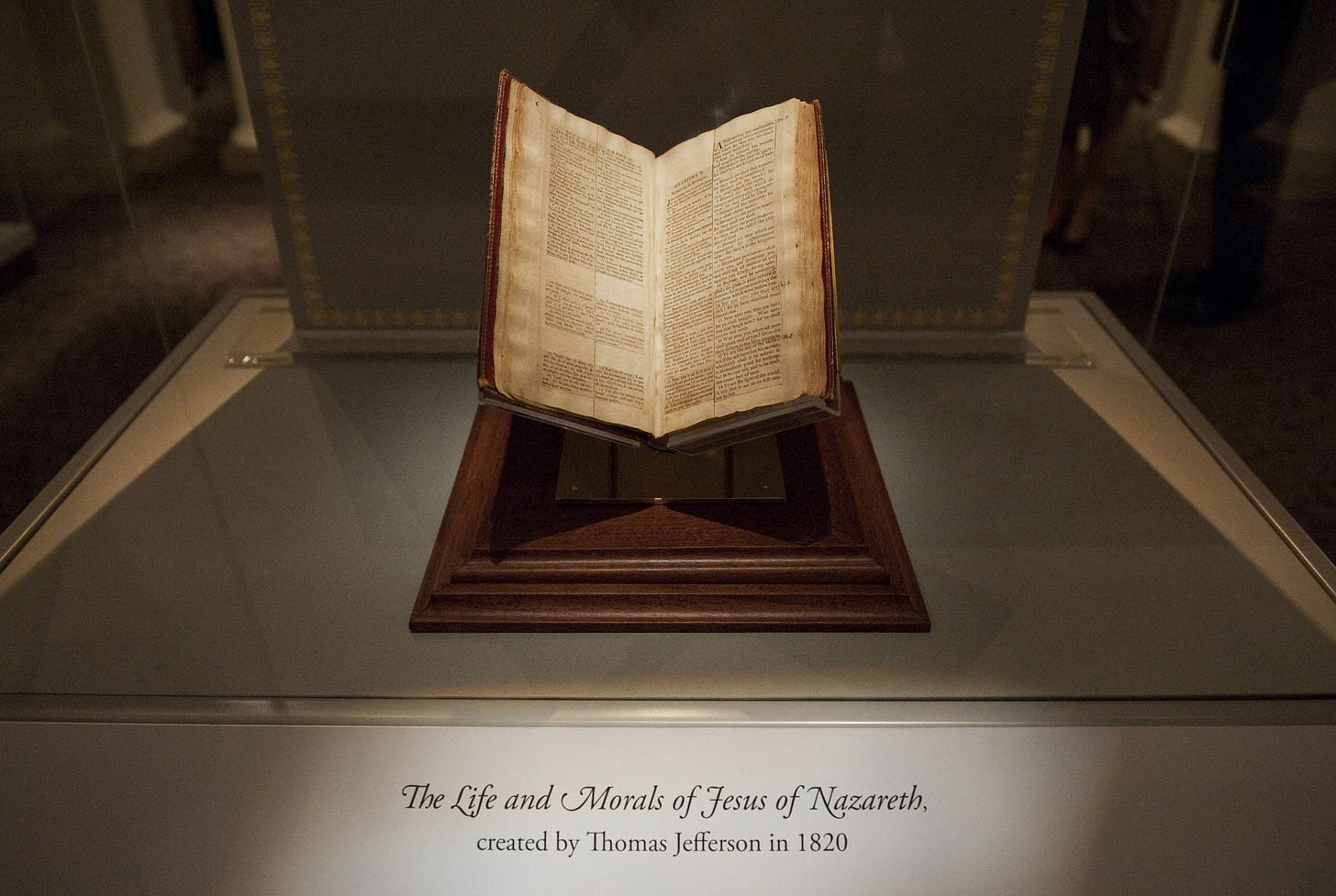

The result—a short text titled The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth, Extracted Textually from the Gospels in Greek, Latin—is the subject of a short but fascinating new monograph. Peter Manseau’s The Jefferson Bible: A Biography, part of Princeton University Press’s series on religious texts, is less an exhaustive study of Jefferson’s religious beliefs than a focused chronicle of his Bible’s nineteenth-century birth, loss, and resurrection. As a curator of American religious history at the Smithsonian Institution, Manseau is a natural candidate to detail the Jefferson Bible’s strange journey from its creator’s hands to the Smithsonian’s holdings and beyond. Manseau calls The Life and Morals “an ambivalent scripture that has taken on an outsized significance in a nation for which religious ambivalence is the one enduring creed.” But his narrative suggests that Jefferson’s Bible is less a meditation on ambivalence than a quest for certainty—a theme which abounds in American culture, for better or worse.

If there’s one thing that Manseau makes clear about Jefferson’s religious evolution, it’s that America’s third president had little use for mystery. While Jefferson was raised an Anglican, his study of natural philosophy under the tutelage of William Small introduced him to “the works of John Locke, Francis Bacon, and Isaac Newton, whom for Jefferson quickly became a new trinity to replace the old.” Believing that the world was made to be perfectly understood, he rejected the contradictions inherent to Christianity and instead immersed himself in works by religious critics like Viscount Bolingbroke and Joseph Priestley. Priestley in particular held that “nothing can be alleged from the New Testament in favour of any higher nature of Christ, except a few passages interpreted without any regard to the context, or the modes of speech and opinions of the times in which the books were written”—a view which profoundly influenced Jefferson’s thought.

After working to protect the political rights of religious (and irreligious) minorities in his home state in the 1780s, Jefferson faced a tidal wave of Federalist critics accusing him of harboring depraved atheistic designs during the presidential elections of 1796 and 1800. Although he did not answer his attackers publicly, Jefferson privately bristled at the notion that he was a dangerous infidel. He had once conceived of a project to compare the teachings of the world’s great classical philosophers, but by 1803 his attention had narrowed on Jesus, whom he called the “first of human Sages.” And so, determined as “a real Christian” to rescue Jesus from the “Platonists” who had corrupted his teachings with anti-intellectual dogma, Jefferson bought four translations of the New Testament and began his own exercise in biblical criticism.

Using a sharp implement, he surgically cut out every instance in the Gospel narrative between Jesus’s birth and crucifixion that met the standards of Enlightenment rationalism. The task, in Jefferson’s telling, was as easy as separating “diamonds from dunghills” or “gold from the dross.” He then pasted these fragments onto blank pages that in his retirement he bound into a red leather volume and read from in the evenings. Jefferson’s remix of the Gospels eliminates the virgin birth, miracles, the forgiveness of sins, and the resurrection. Only the “morsels of morality” constituting Jefferson’s spoken parables and teachings remain.

In reviewing the Jefferson Bible’s structure, Manseau offers a bit of incisive textual criticism of his own. Having excised the very miracles that fueled Jesus’ popularity by giving his followers reason to believe his radical teachings, The Life and Morals is left as a Gospel that is at best incoherent, at worst callous. “Jefferson’s Jesus seems to be able to heal but mostly chooses not to do so,” Manseau explains. “[His] stories are all set up with no pay off.”

A review of the Smithsonian’s facsimile of The Life and Morals, however, reveals that Jefferson did include a few passages that arguably fail to pass his own test of rationality. Even as beggars retain their blindness and water its molecular structure, Jefferson’s Jesus speaks frequently of the decidedly unscientific afterlife and of his role in its adjudication. The parable of the tares—carefully pasted together in its entirety from Matthew 13—is a notable example: “The Son of Man shall send forth his angels, and they shall gather out of his kingdom all things that offend, and them which do iniquity; And shall cast them into a furnace of fire: there shall be wailing and gnashing of teeth.” That Manseau does not delve into the possibilities for why Jefferson would allow himself the comfort and terror of a life beyond the material world that he held in such inestimable value is a strange omission—especially since the language of eschatology colors one of his most prescient pronouncements on the future of slavery in the United States: “Indeed I tremble for my country when I reflect that God is just: that his justice cannot sleep forever.”

Even if Manseau doesn’t engage with Jefferson’s incongruent attitude toward the next world, the second half of The Jefferson Bible ably traces its namesake’s anastasis. Jefferson never intended to share the details of his Biblical reconstruction with anyone who was not already a trusted confidant, lest it fuel further outrage from religious circles. He bequeathed The Life and Morals to the Randolph branch of his family, where it remained hidden from the public for nearly a century—until Cyrus Adler, director of the Smithsonian’s religion division, succeeded in locating and purchasing it from Jefferson’s great-granddaughter, thereby rescuing it from obscurity.

Adler unveiled The Life and Morals at the 1895 Cotton States International Exposition in Atlanta as part of an exhibition on “biblical archaeology,” but Manseau argues that Adler likely viewed The Life and Morals as more than just a peculiar example of exegesis. To him it was a relic of America’s revolutionary religious tradition. An Orthodox Jew, Adler held a special appreciation for what the Jefferson Bible represented to those who did not conform to the religious sects that predominated in the United States. As he noted years later in an address to the National Conference of Catholics, Jews, and Protestants, “The beginning of the Republic meant . . . [that] so far as matters of religion are concerned there are no majorities or minorities. All people may worship God according to the dictates of their own conscience with reference to the question as to whether the particular form of worship or belief has many followers or few.”

Adler well understood the animating philosophy behind The Life and Morals. But as Manseau delves into its reprint history, one learns how Jefferson’s scrapbook has been transfigured to meet competing interpretations of appropriate religious practice in the United States. To John Fletcher Lacey, the Iowan representative who succeeded in reprinting and distributing thousands of copies of The Life and Morals to members of Congress at the turn of the century, the Jefferson Bible was a “test” proving Christianity’s inherent rationality. To Reverend Dr. Henry Jackson, a Presbyterian minister and self-professed “social engineer” who edited a 1923 edition of The Life and Morals, the work was a proselytizing tool that “democratize[d] religion” by putting “Jesus’ principles into common speech.” In the 1960s, Unitarian minister Donald Harrington argued in his introduction to yet another edition of the Jefferson Bible that it offered an opportunity for Christian churches to save themselves from declining religiosity by turning away from the “myths” that muddied Jesus’s message of perfect love. And as the culture wars took off in the 1990s, evangelicals like David Barton used The Life and Morals to implausibly present Jefferson as an orthodox Christian while secular humanists mobilized it as an example of critical methodology that should be applied to other religions.

If there is a unifying theme among these perspectives, it is that the temptation to wield Jefferson’s blade of epistemological certainty is embedded in American discourse. Unspoken is the question whether it makes our civil society healthier. It is indisputable that one of the greatest gifts Jefferson left this country was to decouple religion from political power; to give every woman and man the opportunity to form their own consciences without the direction of the heavy hand of the state.

But in this empowering freedom, danger lurks.

Although Jefferson once asserted that “your own reason is the only oracle given you by heaven,” it is all too clear how often his own reason failed him. Despite having produced one of history’s most important statements of human rights, his reason allowed him to mentally compartmentalize the regular abuse of human rights that sustained his livelihood and gave him descendants. In his second term in office, he instituted a disastrous embargo that decimated industries in the Northeast, his reason driving him to put his faith in an “experiment” in weaponizing trade barriers instead of listening to citizens who begged for relief. And near the end of his life, his reason led him to predict confidently that “there is not a young man now living in the US. who will not die an Unitarian.”

This final point is bleakly hilarious, given what the world saw transpire at the Capitol building on January 6. For it is not sensible Unitarianism that many of the young men and women in America have given themselves over to, but a bizarre and insidious mixture of deranged Christian nationalism and gnostic conspiracy theory (Manseau has been chronicling the insurrectionist mob’s religious overtones using the hashtag #CapitolSiegeReligion). Jefferson’s genius lay in pushing the boundaries of possibility for human freedom, but in the process, he lost sight of some inescapable truths of the human condition. Even in freedom, people need and hunger for formation. And if they can’t find it in traditional institutions, they will look elsewhere—to self-proclaimed prophets, to memes, to message boards in the darkest corners of the internet—to find something that can fill that existential void.

While covering the attack on the Capitol, Tim Carney reported an extraordinarily Jeffersonian refrain among the protesters that he interviewed: “I do my own research.” When pressed as to their church attendance, many admitted that they did not regularly attend services, but rather studied the Bible on their own. This anecdotal evidence largely squares with data from a recent report by Louisiana State University sociology professors Samuel Stroope and Heather Rackin, which found that support for Donald Trump and Christian nationalism was highest among those who identified as Christian but were not formally affiliated with a church. As Stroope explained, “Institutions in general can have a stabilizing effect on people’s lives and ideologies” by complicating members’ views and offering guidance that obviates the need to turn to authoritarian figures in unmooring times. Manseau himself has recently published a heartbreaking account of how a Baptist pastor worked to steer a member of his congregation away from the polarizing pull of his social media account during the pandemic, seemingly succeeding for several months—before the man became one of the insurrectionists chasing Officer Eugene Goodman up a stairwell at the Capitol on January 6.

Churches are obviously not a silver bullet against what ails us today. There are good reasons why traditional churches have lost trust in recent decades—many stemming from horrifying abuses of their authority as moral arbiters. But their decline has created an opportunity for even more monstrous things to emerge. Part of the solution, therefore, may not be exodus from organized religion, but a rededication. Those who have left churches should reconsider the benefit for themselves and their community of returning to their faith and pursuing institutional change from within, not without. In doing so, they might help churches become spaces for the radical encounter that a healthy polity needs. After all, rich intellectual traditions of nuance and debate are at the heart of many religious denominations. By engaging with them and encouraging others to do so as well, it is possible to short-circuit the impulse towards excision and solipsistic certainty that ultimately threatens a pluralistic society.

In his epilogue, Manseau poignantly notes that for a time it was almost impossible to open The Life and Morals as its binding was “so inflexible that the tension it created was now a threat to the pages it held.” Whether Jefferson and Washington were heterodox Christians or “theistic rationalists,” inflexibility is what ultimately distinguished the former from the latter. The insight that Jefferson lacked, but that Washington had in abundance, is that the freedom they had fought so bitterly to secure could not be maintained in a vacuum. Washington therefore modeled the importance of a life framed by freely chosen religious participation, even as he did so in a manner congruent with the particularities of his conscience. It was a sign of faith that the wide range of religious traditions flourishing in the United States could serve as bulwarks against tyranny in the New World even as they had aided tyrants in the Old. Holding to his deep personal convictions while humbly acknowledging that the road to virtue is not trod alone, Washington possessed a truly peculiar mind.