“We haven’t lost anything. And we’re not going to lose anything,” a defiant Vladimir Putin asserted last Wednesday, at the plenary session of Russia’s Eastern Economic Forum in Vladivostok, answering a question about what Russia had lost and gained because of the war in Ukraine that began on February 24.

Putin’s declaration may not make it on a list of famous last words, but it did effectively signal the start of a spectacular rout of Russian armed forces in Ukraine. On Thursday, the long-anticipated Ukrainian counteroffensive, which at first appeared to fizzle or at last slow down dramatically near Kherson, took off for real in the Kharkiv region. Advancing Ukrainian troops plowed rapidly and ruthlessly through Russian lines, recapturing the towns of Balakliya, Kupiansk, and Izium—a key point on Russian supply routes—as well as numerous villages. On Sunday, the Ukrainian government said its forces had retaken over retaken over 3,000 square kilometers (1,100 square miles) of territory; these claims are still unconfirmed, but the Institute for the Study of War also tracks stunning Ukrainian gains:

On Saturday, the Russian Ministry of Defense formally acknowledged the retreat in its own way: “In order to achieve the stated goals of the special military operation to liberate Donbas, a decision has been made to regroup the Russian troops deployed in the Balakliya and Izium districts.” Given the abundant evidence of a hasty Russian flight, with weapons and equipment left behind, this sounds like Baghdad Bob-level spin. Or one could reach for a Russian analogy: the brilliant 1944 satirical play The Dragon by Evgeny Schwartz, about which I wrote at the start of April when the absurdity of Russian claims that the war was proceeding “according to plan” was already becoming clear. Now, Schwartz’s political fairy tale, in which a heroic knight has to battle a dragon who has ruled over a subjugated town for 400 years and cultivated a small army of human flunkeys, is more relevant than ever. “Look, look! The dragon’s on the run—someone’s chasing him all over the sky!” shouts a little boy in the crowd watching the battle in the town square, only to be shushed by one of the grown-ups: “He’s not on the run. He’s maneuvering.”

Meanwhile, the weekend brought an understandable euphoria among the pro-Ukraine commentariat in the West, with predictions of a likely or certain Ukrainian victory—defined as the retaking of all the territory Russia has de facto controlled since 2014—and, at least as of Sunday evening, an embarrassed silence among the anti-anti-Putin set that has long accused the media of peddling a phony narrative of Ukrainian successes.

Yet it is much too early to bury the dragon. Even reports that Russian frontlines in the Kharkiv region have “collapsed” may be too optimistic: fighting reportedly continues on the outskirts of Lyman, a town still occupied by Russian troops, and on Sunday morning Russian forces shelled recently liberated Kupiansk. And, of course, the Russians are still in control of three major cities further south: Kherson, Mariupol, and Melitopol.

Still, even without premature victory celebrations, it is clear that the momentum, for now, is on the Ukrainian side—and that, if nothing else, the Ukrainian victories of the last few days have dealt a severe psychological blow both to Russian armed forces and to the war-cheerleading machine. There are reports of hawkish Russian war bloggers turning bitterly against Putin and declaring the war a “catastrophe.” But on Friday, there was also a remarkably candid discussion of the state of the war in Ukraine on the live show Mesto vstrechi (“Meeting Place”) on NTV, the sadly misnamed “Independent” television network whose seizure by the state-controlled Gazprom leviathan in 2001 was one the early signals of Putin’s authoritarian rollback.

It’s not that the program—subtitled excerpts from which have been posted by Julia Davis’s invaluable Russian Media Monitor service—truly challenged Kremlin orthodoxy: It opened with a voiceover asking how long Kyiv would “continue to terrorize liberated territories,” and there were plenty of comments about Ukraine’s “Nazi regime.” (Plus, in a weird tangent that typifies Russia’s peculiar brand of derangement right now, host Andrei Norkin introduced the program with the observation that the death of Queen Elizabeth could be another harbinger of the West “falling apart.”)

And yet there were some remarkably outspoken voices of dissent, at least by the standards of the post-February 24 Russian media environment. One of them was Boris Nadezhdin, a former Duma member, onetime close ally of murdered opposition leader Boris Nemtsov, and more recently a consistent though cautious critic of the Putin regime. Along the same prudent lines, Nadezhdin did not blame Putin himself but only unnamed “people who convinced President Putin that the special operation would be effective and swift, that we won’t be hitting the civilian population . . . that the Ukrainians will surrender and run away and ask to join Russia.” Nonetheless, his criticism was scathing, and he made it clear that he favored peace negotiations that would end the war. And yes, he repeatedly called it a “war,” despite the official prohibition on that word with regard to Russia’s “special operation” in Ukraine—and two stern reminders from fellow panelist and current Duma member Alexei Kazakov to “watch the rhetoric.”

“We have reached the line beyond which we need to understand a simple thing: to defeat Ukraine with the resources with which Russia is currently trying to wage war, in the regime of colonial warfare—contract soldiers, mercenaries, private military companies—is absolutely impossible,” Nadezhdin said flatly. Later, he sparred with Kazakov, who insisted that the conflict in Ukraine was part of a “global war” between Russia and the West and that Russia had to achieve victory over Ukraine no matter how long it takes. “So my ten-year-old children will still have time to fight in this war, am I understanding you correctly?” Nadezhdin inquired sarcastically. Kazakov reassured him that one should not overestimate either Ukraine or the West; but the assurance rang hollow, especially since he had just admitted that Russia had been dealt “a very sensitive psychological blow” by the last few days’ developments in Ukraine.

At least two other guests were also in openly critical mode, mocking claims from early in the war that Russians would be greeted by Ukrainians with open arms and taking a skeptical view of Putin’s “we haven’t even gotten started in earnest” bluster: if so, quipped political scientist Viktor Olevich, “now would be a good time.”

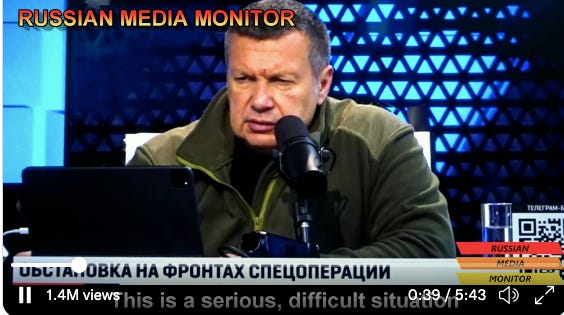

On the same day, Russian TV’s foremost Kremlin shill, Vladimir Solovyov, acknowledged that the situation was “alarming” but tried to stem the flow of bad news on his online show Full Contact with Vladimir Solovyov. He warned against “hysteria,” assured his audience that personal sources in the military had told him “Balakliya is still ours,” and chided those who would treat war like a sports event with scorekeeping rather than “arduous male work.” The surreal effect of this half-hearted spin was heightened by the fact that Solovyov had visible and unexplained cuts on his face:

Speculation was plentiful, but there was a certain symbolism in the fact of a morose and battered propagandist trying to deal with news of Russian troops taking a beating.

Whether more “psychological blows” in Ukraine will significantly damage Putin’s standing is, of course, the big question of this conflict. Even before the Ukrainian offensive scored its stunning victories, two small-scale and doomed but nonetheless remarkable challenges to Putin were reported from within Russian political structures.

On September 7, a group of municipal representatives in the Smolny district of St. Petersburg sent an official letter to the Duma asking it to initiate treason charges against Putin and remove him from office. The letter noted that, as a result of the “special military operation” in Ukraine, “combat-ready divisions of the Russian army are being destroyed . . . and young, working-age citizens are being killed or left disabled”; “the Russian economy is suffering” because of sanctions and the brain drain; “the NATO bloc is expanding eastward”; and instead of demilitarizing, Ukraine was receiving new armaments.

So far, the only response has been to charge the five deputies who voted to approve the letter with discrediting the Russian armed forces—for now, as a civil violation with a maximum fine of 50,000 rubles ($823) for first-time offenders; subsequent offenses could lead to criminal prosecution and prison terms.

Nonetheless, members of another urban municipal council—this one in the Lomonosovsky district in Moscow—followed suit the next day: they approved an appeal to Putin demanding his resignation. While the Moscow deputies’ appeal was less confrontational than that of their St. Petersburg colleagues—they did not mention treason and praised Putin’s early policies—their conclusions were still uncompromising:

Studies show that in countries with regular transfers of power people generally live better and longer than in countries in which the leader only leaves office feet first. … The rhetoric you and your subordinates use has long been saturated with intolerance and aggression, which had ultimately thrown our country back into the Cold War era. Russia is once again feared and hated, and we are once again threatening the whole world with nuclear weapons.

In consideration of the above, we ask you to vacate your post due to the fact that your views and your model of governance are hopelessly outdated and hinder the development of Russia and its human potential. Both municipal councils apparently have a reputation for rebelliousness, which has been somewhat tolerated in Putin’s Russia on the local level; thus it is hard to tell whether their defiance will nudge other political bodies to speak out. That may depend on how many more “sensitive psychological blows” Russia will be dealt, both on the battlefields of Ukraine and in the domestic sphere where Russia’s industries are starting to feel the bite of sanctions. If the scope of the military losses becomes clear within Russia, the monstrosity of Putin’s declaration that “we haven’t lost anything”—and his claim that the war has only strengthened Russia’s sovereignty—will be much harder to deny.

In The Dragon, the townsfolk remained loyal to their three-headed ruler even the hero lopped off one of his heads and it clattered down into the square (or was “transferred into the reserves,” according to the city government’s spokesman). But once the second head falls, the crowd suddenly wakes up and clamors in dissent, expressing vocal outrage at “that one-headed monster” and his minions. Could the Ukrainian counteroffensive turn out to be the fall of the dragon’s first head?

Time will tell. But in the meantime, Putin’s weekend was marked by one more event that, while ostensibly unrelated to Ukraine, is both emblematic of Potemkin-style Russian swagger and inescapably symbolic. On Saturday, even as Russian soldiers were getting pounded in Ukraine, Putin took the time to speak, via video, at the opening of a new Ferris wheel in Moscow—which has the distinction of being the largest in Europe and is called “The Sun of Moscow.” Alas, on the day of its debut, the wheel stopped several times, leaving unhappy riders stuck as high as 460 feet above ground. On Sunday, the wheel was temporarily closed to visitors for “recalibration.”

The ancient Romans would have seen this as an omen.