Supreme Court Summarily Smacks Down Wisconsin Electoral Maps

Its unprecedented move comes even as Ketanji Brown Jackson explains to the Senate how judges are supposed to judge.

The Supreme Court’s latest “shadow docket” ruling—handed down yesterday in the midst of Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson’s confirmation hearings—is, at best, befuddling. At worst, it’s breathtaking in exposing the Court’s willingness to summarily sweep away a state court’s considered judgment.

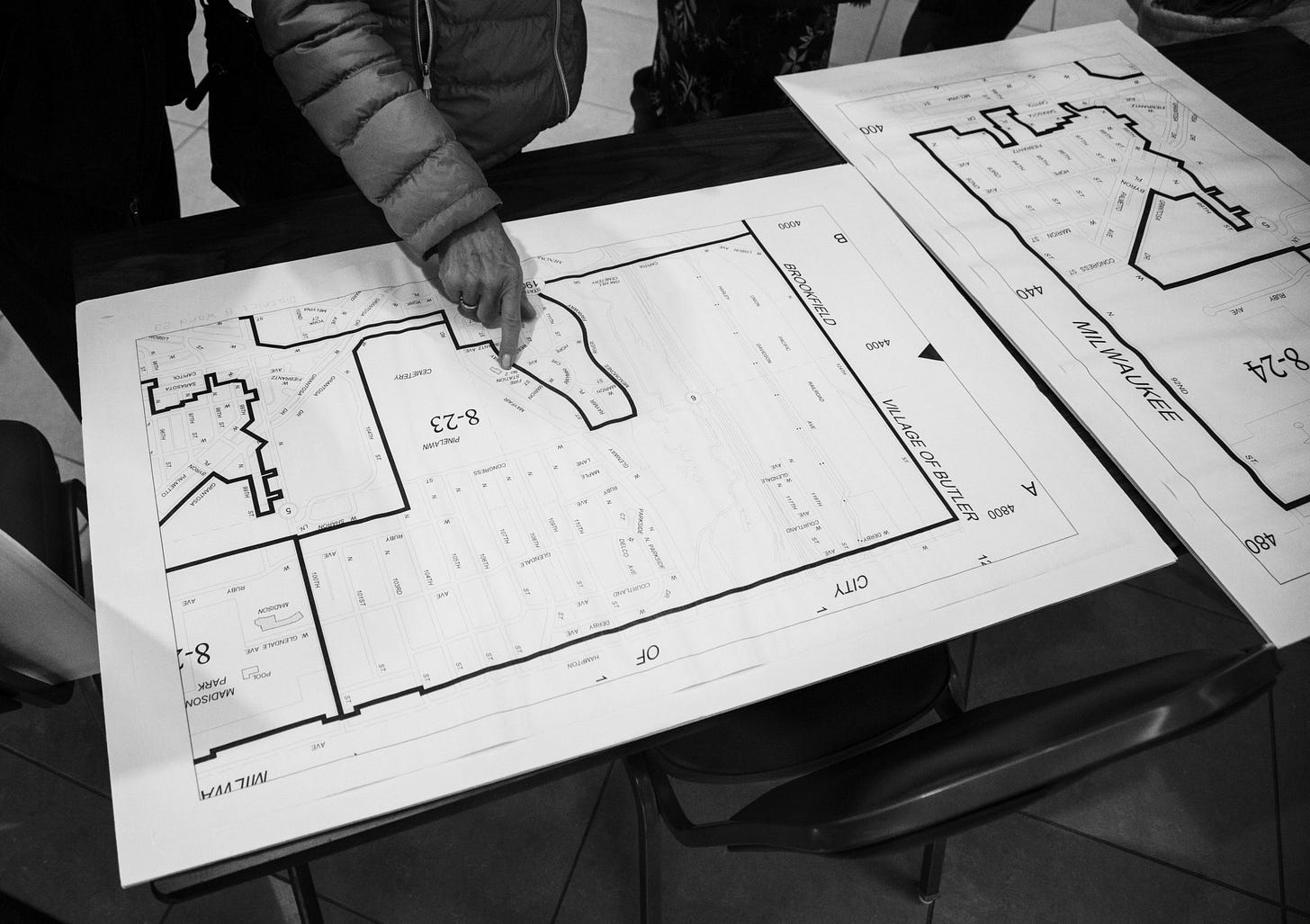

In a twelve-page per curiam opinion (meaning no justice claimed authorship), a divided Court granted an emergency application for a stay of a Wisconsin state court’s decision regarding that state’s electoral maps. Last November, following the 2020 census results, the Republican-controlled Wisconsin legislature drew new electoral maps for both the seats in the state legislature and for congressional districts. Democratic Governor Terry Evers promptly vetoed the maps, describing them as “gerrymandering 2.0.” With the process stalled and the 2022 election drawing near, the Wisconsin Supreme Court agreed to step in, explicitly noting that its involvement would be limited because redistricting is usually supposed to be a matter for the political branches of government. The court invited the legislature and the governor, as well as other parties to the litigation, to submit their preferred electoral maps. On March 3, in a ruling that meticulously laid out its reasoning, the court selected the maps that Governor Evers proposed.

Wisconsin Republican lawmakers petitioned the U.S. Supreme Court for an emergency injunction of the state supreme court decision regarding the state legislature maps—and in yesterday’s decision, the Court granted that injunction, ruling that the Wisconsin Supreme Court “committed legal error” by accepting the governor’s maps. The governor’s proposed map of state assembly seats, which the state supreme court had accepted, revised the existing districts to enhance participation by people of color, increasing the number of majority-black districts in the state assembly from 6 to 7 (out of 99 total districts). In its ruling yesterday, the U.S. Supreme Court agreed with the petitioners that the Wisconsin court had “selected race-based maps without sufficient justification, in violation of the Equal Protection Clause.” In other words, the petitioners argued that enhancing the voting power of black voters actually violated the Constitution.

In its March 3 ruling, the Wisconsin Supreme Court explained how it had determined that the governor’s map complied with the Constitution and, although not necessarily required by the Voting Rights Act, likely complied with that law too. Yet the U.S. Supreme Court was unpersuaded that the Wisconsin Supreme Court’s decision should stand. It reasoned that race-based districting is acceptable only if the state shows “that it had ‘a strong basis in evidence’ for concluding that the statute required its action,” and that “a race-neutral alternative that did not add a seventh majority-black district would deny black voters equal political opportunity.” The Wisconsin court didn’t do enough to make that showing.

Because the Court’s ruling was issued as a per curiam opinion, we don’t know what the breakdown of the vote was—but we know that at least two justices disagreed with the ruling, since Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote a dissent, in which Justice Elena Kagan joined. Here is how the dissent begins:

The Court’s action today is unprecedented. In an emergency posture, the Court summarily overturns a Wisconsin Supreme Court decision resolving a conflict over the State’s redistricting, a decision rendered after a 5-month process involving all interested stakeholders. Despite the fact that summary reversals are generally reserved for decisions in violation of settled law, the Court today faults the State Supreme Court for its failure to comply with an obligation that, under existing precedent, is hazy at best.

To be clear: My problem with this ruling isn’t on the merits of the law. The legal questions are complex, nuanced, and unsettled. It’s the back-of-the-envelope way in which the Court reached a decision applying what amounts to unsettled law that is disturbing. Without full briefing or oral argument, and thus without the benefit of a full airing of all the legal and factual elements from all sides of the issues (as has been the practice of the Supreme Court for over two centuries, with rare exceptions), a handful of unelected judges took a swipe at comity and respect for other sources of government. Here, the state of Wisconsin—its courts and its governor.

Ironically, the Supreme Court handed down its ruling on the third day of Judge Jackson’s grueling confirmation hearings—a day when Mitch McConnell, the Senate minority leader, accused Jackson of having “used every possible ounce of discretion to essentially remake . . . policy from the bench” in applying Congress’s sentencing guidelines as a federal trial court judge.

By any stretch, Judge Jackson is not the judicial policymaker we need to worry about right now.

What’s especially shocking about yesterday’s decision is the Court’s apparent inconsistency with another recent shadow docket ruling involving gerrymandering in Alabama. In that case, the Court issued an emergency stay that put back in place a federal electoral map that a three-judge panel had determined violated the Voting Rights Act, to the detriment of minority voters. Only one of the seven districts in the Alabama plan is a majority-black district despite a relatively higher population of black residents in the state. There were two Trump appointees on that lower court panel which, like the Wisconsin Supreme Court, took great pains to build a record and analyze the issues thoroughly. The Alabama case involved a seven-day hearing with 17 witnesses and over 1,000 pages of briefs. Even Chief Justice John Roberts dissented in that case.

So it may be “heads, white voters win; tails, black voters lose” when it comes to the Voting Rights Act and the modern Supreme Court. Let’s hope not. But it’s the potential for such hypocrisy that makes the Court’s addiction to shadow docket rulings so problematic. With a full set of opinions issued after months of briefing and oral argument, it would be possible to square the legal circles in a measured way that is mindful of protecting the legitimacy of the Court in the process. But with the exception of Roberts, this majority doesn’t seem to care.

Bear in mind too that senators repeatedly asked Jackson about how judges judge. She answered that judging involves the methodical application of a multitiered methodology—not reactive ideology. Regardless of their political leanings, all good judges consider the text of the Constitution or a statute. When language is ambiguous, they look at prior case law, careful to adhere to precedent—a practice known as stare decisis—on the rationale that honoring precedent lends predictability and legitimacy to the judicial system. Stare decisis also ensures that judges don’t stretch out too far beyond their job descriptions.

It’s exclusively the role of trial judges to develop a factual record through witnesses, documents and other materials. Only legitimate, verifiable facts go before juries, who—like trial judges sometimes—are tasked with deciding which version of events to believe. Appellate judges, including on the Supreme Court, review the record mostly for error. They don’t make up new facts. And they reverse only reluctantly. That’s the deal.

Jackson herself explained for the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit, in a case rejecting former White House counsel Don McGahn’s bid to snub a congressional request for testimony, that you don’t have to be a constitutional scholar to understand one basic tenet of American government: Presidents are not kings. That goes for judges, too.