The headlines tell the story: A decades-long military effort is ending. Americans and their allies are desperately hustling to secure safe passage out of the fallen country. Where exactly these tens of thousands of allies will end up or how they will be received is anybody’s guess. They are a living reminder of America’s humiliating exit from a war in which all the money and firepower in the world were no match for a more determined—and far more unscrupulous—foe. If America couldn’t keep the entire country safe, then at least the most vulnerable of the allies can be spared the most horrible of outcomes under the new regime.

This summary could well be describing the current evacuation of American allies from Afghanistan, where a twenty-year occupation has come to an end, with perhaps some successes but also at great cost—estimated by some at an average of $300 million per day. However, the description applies also to the end of the Vietnam War back in 1975. These wars took place at different times under different circumstances, but there are enough parallels that we can draw from the past to help us make better informed decisions in the present—especially as relates to the plight of refugees.

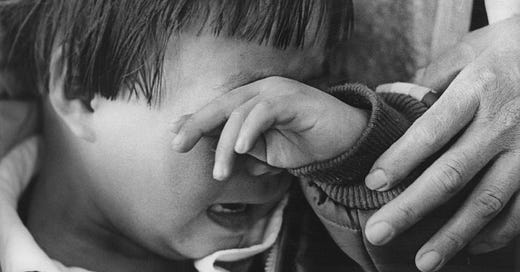

“I hope that the Lord spares me from ever seeing anything like this again,” a U.S. diplomat confessed to the press when the last flights left Saigon at the end of April 1975. “It is heartbreaking. It is seeing people naked—without any dignity left.” There was something morally indefensible about leaving a people to fend for themselves after spending the previous thirty years telling the entire world that communism posed the greatest threat to humankind. It was thus a terrible failing of the Voice of America to intentionally omit any bad news during the final weeks of the war. “It was not, to put it mildly, one of our better days,” as one former VOA employee said. A profound sense of national guilt had united a large swath of liberals and conservatives in redeeming the nation’s soul. The war was lost, but the postwar was still up for grabs. President Gerald Ford made plans to evacuate tens of thousands of Southeast Asian allies in record time.

Rather than reflect too long on defeat, the New York Times and other American outlets shifted the narrative to stories of redemption when they declared the “rescue” of 130,000 Southeast Asian allies “one of the few shreds of glory that the United States has been able to retrieve from the closing days—or years—of the Vietnam war.” The right-wing editorial page of the Orange County Register felt the same way:

Breathes there an American who has not resonated to the legend chiseled on the base of the Statue of Liberty, those words about welcoming the tired, teaming masses, the refuse, etc.? We have to accommodate [the refugees], absolutely must. Of course they will burden the job market; there is no denying such a consequence. But . . . we’ll think of those practical matters later; right now we must think of the moral imperative.

A chorus of populist/nativist rhetoric from the left and right was countered by a more centrist coalition of liberals and conservatives strong enough to break through the hate and cynicism. Liberals felt guilty about escalating an unwinnable war, while conservatives wanted the United States to atone for abandoning allies in need. Each side had its own reasons, but the outcome was the same. Jerry Brown, the Democratic governor of California, was forced to defy his white working-class base because he realized that the South Vietnamese had never asked to be refugees. A pre-xenophobic Pete Wilson, then mayor of San Diego, extended his city’s “warmest wishes” to the new arrivals, citing their “courage and strength” as “an example for all our children.”

In the three other states (Arkansas, Florida, and Pennsylvania) where Vietnamese refugees would be temporarily housed in 1975, voices of moderation in both parties were able to prevail. Extremists had their hour early on, some holding signs in Arkansas that read “Gooks Go Home.” An employee of the John Birch Society in Florida told the New York Times that, “There’s no telling what kind of diseases they’ll be bringing with them.” Anti-refugee constituents sent scores of letters to their U.S. senators.

When refugees actually arrived, though, they were received with open arms. In Arkansas, Governor David Pryor personally welcomed the first arrivals to Fort Chaffee while a local high school band played a stirring rendition of the “Star-Spangled Banner.” In Pennsylvania, a welcoming committee of three hundred, including Governor Milton Shapp, warmly greeted refugees to Fort Indiantown Gap. There were similar scenes in California and Florida, where the centrist consensus was that a gracious welcome was the least that could do be done for people who might never again be able to see their family and friends in the homeland.

We are starting to see some signs of that spirit as Afghan refugees trickle into the United States. USA Today published an editorial last week welcoming them to the country, as have other news organizations. Utah’s Republican governor, Spencer Cox, expressed a willingness to help in any way possible because “Utah was settled by refugees fleeing religious persecution.” The Republican mayor of Blackstone, Virginia, Billy Coleburn, struck a positive tone upon learning that up to 10,000 Afghan refugees would be temporarily sheltered at Fort Pickett Army base near his town, calling them “freedom fighters who risked their lives and the lives of their family members to give to the American servicemen and servicewomen.”

Nearly fifty years ago, it was an unprecedented bipartisan humanitarian operation that helped redeem this country’s soul after a long and disastrous war. If we step away from partisan politics long enough, it could do so again.