Wendell Berry’s Peculiar Patriotism

In a big new book, the farmer-philosopher makes a case for preserving Confederate statues—but leans more on sympathy than on history.

In 1934, Kentucky-born artist Ann Rice O’Hanlon created a fresco on a wall in the lobby of the University of Kentucky’s Memorial Hall, a church-like structure completed five years earlier as a tribute to the soldiers from the Bluegrass State who died in the world war. Commissioned through the Public Works of Art Project, a New Deal program, O’Hanlon’s fresco depicted not a sanitized history of Kentucky, but one that included skirmishes between settlers and Native Americans, as well as a depiction of enslaved African Americans working the fields and others playing music for white dancers.

The fresco has always been remarkable, attracting praise for its originality and censure for its racial depictions. In 2015, the president of the university, Eli Capilouto, in response to black student leaders who expressed opposition to the fresco, chose to shroud it. Since then, the university has wavered in its approach to the fresco. In 2017 the fresco was uncovered and explanatory signage was installed. The next year, the university commissioned the Trinidadian-born artist Karyn Olivier to create a companion artwork, entitled Witness, alongside the fresco. In the dome of Memorial Hall, Olivier painted these words of Frederick Douglass: “There is not a man under the canopy of heaven, that does not know that slavery is wrong for him.”

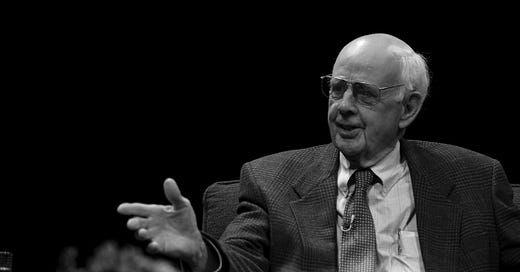

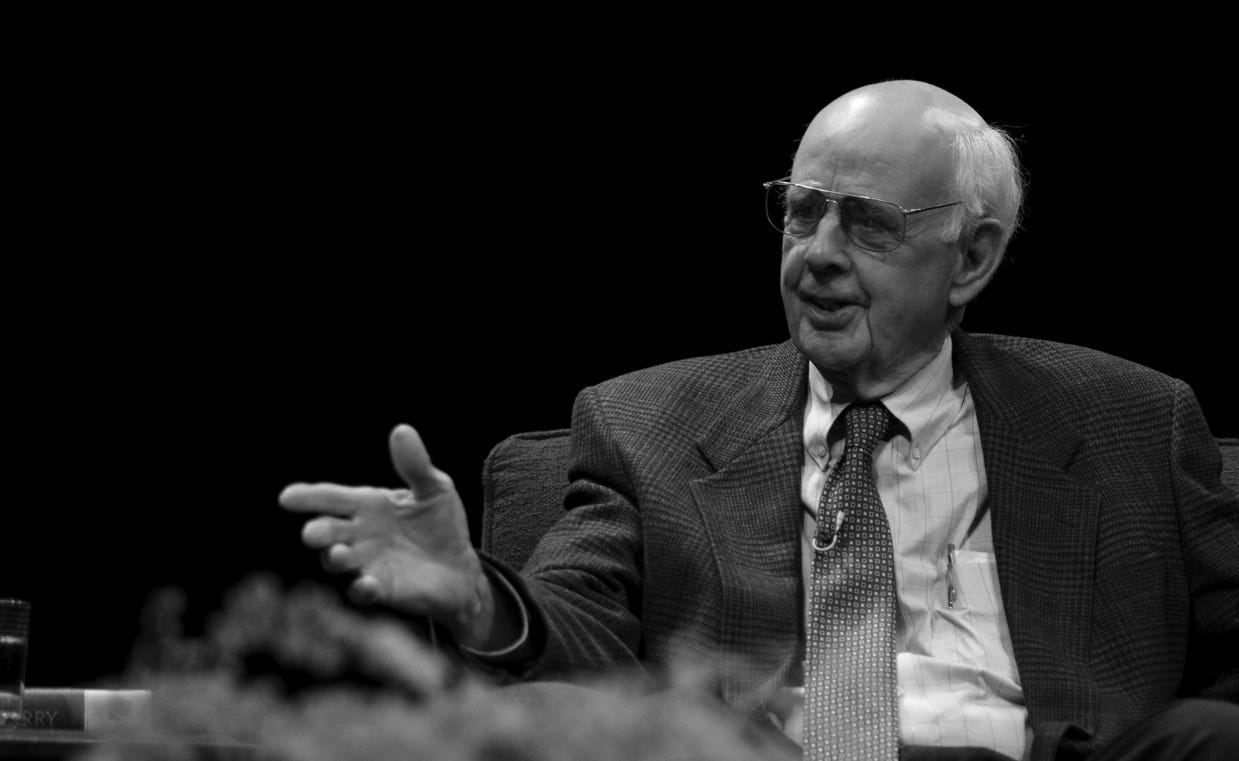

After the mural was shrouded in 2015, Wendell Berry wrote an op-ed about it for the Lexington Herald-Leader. “Ann painted the Memorial Hall fresco in 1934,” he wrote, “when it took some courage to declare so boldly that slaves had worked in Kentucky fields. Nobody would have objected if she had left them out.” Berry wasn’t writing only as a University of Kentucky alumnus and former professor, or as one of the commonwealth’s preeminent literary figures, but as someone who “knew well and for many years” Ann Rice O’Hanlon; Berry’s wife, Tanya Amyx Berry, is the late O’Hanlon’s niece. Berry’s long relationship with the university has at times been contentious; back in 2010, he removed his papers from the university’s archives following the men’s basketball program’s acceptance of coal money for a new dormitory. But, as his recent book, The Need to Be Whole, reveals, his intervention in the fresco controversy wasn’t just about his relationship to the artist or his problems with the university; it was a preview of coming attractions.

It feels like Berry is one of those writers more discussed than actually read. He has his famous champions, including Alice Waters and Nick Offerman, and is touted widely as a prophetic voice on environmental and agricultural concerns. His poetry is lauded, and his fiction enjoyed by a devout group who almost consider themselves fellow initiates into what he calls the “Port William Membership”—Port William being the fictional avatar of Port Royal, the Henry County, Kentucky community that Berry was born into and has watched slowly and inexorably decline. Part of his vast nonfiction corpus has been dedicated to the discussion of that fading past and difficult present, starting with his 1969 collection of essays The Long-Legged House. Most of his subsequent nonfiction likewise consists of essays, but occasionally he has set his hand to producing standalone books.

The Need to Be Whole positions itself as a spiritual descendant of two of these standalones: The Hidden Wound (1970), in which Berry took up the damage wrought by slavery and racial prejudice, and The Unsettling of America (1977), in which he considered the death of the small farm, and more generally the continual destruction of land that was settled even before Europeans arrived in the New World. The new book braids these concerns together, but it lacks a clear rationale: Berry attempts a summing up, but in the process spins out so many arguments and sub-concerns and asides (some of them in this 500-page volume long enough to be books on their own) that his reach towards comprehensiveness risks overwhelming his purpose. Furthermore, some sections, particularly those broadly concerning the Civil War, Robert E. Lee, and Confederate monuments, seem almost designed to spark controversy, though I take Berry at his word when he maintains his sincerity and abiding faith in love as his preeminent value. At the same time, Berry’s writing is marked by a strain of defensiveness I have not previously encountered in his essays, and while this does not necessarily mar the book, it renders it less than what it should be.

Berry’s book on the psychic and material tolls of racism, The Hidden Wound, recounts his slaveholding ancestors as well as his memory of significant pre-adolescent relationships with two black people, Nick Watkins, who worked for his grandfather, and Nick’s companion, Aunt Georgie Ashby. Berry recognizes that his attempt to capture them on the page tends to diminish their humanity: “And so, though I can write about Nick and Aunt Georgie as two of the significant ancestors of my mind, I must also deal with their memory as a live resource, a power that will live and change in me as long as I live. To fictionalize them . . . would be to give them an imaginative stability at the cost of oversimplifying them.” This desire to navigate the intractability of representing cross-racial understanding while nevertheless maintaining deep sympathy attracted many people to Berry’s book, not least among them the late Kentucky-born bell hooks. As she recounted in Belonging: A Culture of Place (2009), “This is the work by Berry that I consistently teach. . . . Shame-based memory of both past and present domination and subjugation of black people by white people has led to a deep silence which must be continually broken if we are to ever create here in our native place a world where racism does not wound and mark all of us every day.” As hooks was unafraid to part with Berry’s thinking when necessary, her recognition of its value becomes all the more worthwhile.

Whereas The Hidden Wound begins from within to search outward, Berry’s book on land and farming, The Unsettling of America, moves from outside to look within. Spurred by a 1967 report by Secretary of Agriculture Earl Butz that, in so many words, told small-holding farmers to make way for mechanized agriculture, Berry moves from the settling of the already-populated continent by European colonizers to consider the unsettling effects of modern agriculture on American society and land. That the continent’s settling required the violent displacement of indigenous people and the labor of enslaved Africans is never far from Berry’s sight, but neither is the subsequent deleterious effects of this settling/unsettling dynamic: “A culture is not a collection of relics or ornaments, but a practical necessity, and its corruption invokes calamity. . . . A healthy farm culture can be based only upon familiarity and can grow only among a people soundly established on the land; it nourishes and safeguards a human intelligence of the earth that no amount of technology can satisfactorily replace.” Much water has passed under the bridge in the intervening half-century, but the great value of these two books lies not just in Berry’s impassioned limning of the circumstances of how we got here, but his refreshingly unapologetic perspective.

By contrast, the defensiveness of The Need to Be Whole jars the reader. Berry traces the new book’s origins to what he considers two missed opportunities: the failure to write a response letter to an advance copy he received of Eddie S. Glaude Jr.’s 2015 book Democracy in Black, and a front-porch conversation with hooks, transcribed in her book Belonging. Tracing the line of thought that passes from his unwritten response through to Glaude to The Need to Be Whole, Berry writes: “More clearly than ever, I could see that both our people and our country have come close to being ruined by race prejudice, or race prejudices, and the continuing effects. But I was worried also about historical and political generalizations that have become too general and too powerful.” So in The Need to Be Whole he hopes to bring clarity to these politically and morally fraught matters, since “clarity is what we owe, in honesty and goodwill, to one another.” But to achieve that clarity, “we will have to submit to complexity.” Unfortunately, in this book, Berry tends to substitute the accretion of material for complexity.

Berry’s singularity as a thinker and his unwavering focus on rural America have long rendered him unintelligible to our dominant left-right political paradigm; his resistance to movements and causes has frustrated those who would co-opt his ideas to their own ends. To wit, consider a representative passage from early in The Need to Be Whole:

The extent to which the Civil War solved the problems that caused it, by any honest accounting, is assuredly limited. It did not stop racism in the South, or in the North. Though it formally ended the Confederacy and secession, it did not end the sectional division, which in fact it ratified and deepened by the further division between winners and losers. . . . So successful were we at solving our own great problem that we have generously undertaken to solve international problems and the problems of other nations also by force of war and with the same assurance of our goodness in doing so.

Very few thinkers would call into question the aftermath of the Civil War and then move swiftly into a denunciation of U.S. foreign policy. Even fewer would use the theological category of sin to do so, but Berry finds the concept little-used in our public discourse when it comes to “the question of what to call our destruction of precious things that we did not and cannot make.” Yet there is a slipperiness to Berry’s language that frustrates any attempt to approach his case systematically. In a chapter titled “Forgiveness,” Berry cogently criticizes the sloganeering that marks contemporary public language an calls instead for a “remedy” of “responsible language” that would be used “to describe in accurate detail, or in detail as accurate as possible, particular persons, places, and things—and also problems, opinions, judgments, thoughts, feelings.” Like so many of Berry’s strictures, it is a tall order, difficult to achieve even for himself.

In one of the book’s more curious sections, Berry expends significant energy reconsidering Robert E. Lee. No doubt he is attempting to “describe in accurate detail” Lee and where he fits into the American story. Berry doesn’t entirely succeed or fail. He acknowledges that Lee was a white supremacist who, while considering slavery an evil, nonetheless executed his father-in-law’s estate with its large number of enslaved laborers, who were to be manumitted within five years, but whom Lee kept in bondage beyond that term in order to pay off the estate’s debts. However, Lee’s “significance” for Berry “is that he embodied and suffered, as did no other prominent person of his time, the division between nation and country, nationalism and patriotism, that some of us in rural America are feeling at present.” Berry’s patriotism towards his own land moves him to “feel for Lee and his finally exhausted army something like the sympathy that I feel for Crazy Horse.” This baffling comparison brings us to one of Berry’s main points: the limits of his definition of patriotism.

For Berry, patriotism indicates fidelity to one’s land and those who live on it and all the responsibilities for care and conservation thus entailed. This is admirably different from the crude way rah-rah patriotism is sometimes invoked in our politics, as when it is employed like a cudgel by the right. But Berry’s usage suffers from its capaciousness: a patriotism that engenders commensurate sympathy for Robert E. Lee and Crazy Horse fails to take account of the profound differences not just between the two men but between their causes and the armies they were arrayed against. Furthermore, there is no position here by which to understand the place of enslaved people, pre- or post-emancipation. While Lee holds a distinctive place in U.S. history, his prominence should afford him no special consideration. Indeed, Berry unwittingly repeats Lee’s inability to see the mass of enslaved people as actors in history who also, in his words, “embodied and suffered . . . the division between nation and country, nationalism and patriotism” that he attributes to Lee.

Berry tries to chart a course between neo-Confederate paeans to Lee’s greatness and the vilifying efforts of progressive historians. That Lee in his terrible humanity embodies neither end of this spectrum could be argued, but to what end? It is tempting to dismiss Berry’s reconsideration of Lee as Southern apologia, but his consistent criticism of U.S. empire, environmental theft and devastation, and the racist treatment of Native Americans, African Americans, and Japanese Americans does not allow such an easy conclusion. Conversely, Berry ignores a rich bibliography that establishes the significance of enslaved culture (e.g., Eugene Genovese’s Roll, Jordan, Roll) and describes the successful self-emancipation of the slaves post-1863 (e.g., W.E.B. Du Bois’s Black Reconstruction in America). While Berry engages with several contemporary black thinkers, including Glaude, hooks, and Ta-Nehisi Coates, and compiles an extensive reading list at the end of the book, the omission of works like those of Genovese and Du Bois represents a crucial missed opportunity.

Throughout The Need to Be Whole, Berry finds little recourse to historical context. He does not consider the plight of the enslaved in light of the Haitian Revolution or even the British abolition of the slave trade. As he does elsewhere, Berry rejects the specialized language and frameworks favored by academics, while fortunately sparing us the denouncements of the 1619 Project and fulminations against Black Lives Matter that have become tiresome features of our public discussion of racism. Nevertheless, his selective historical framework does him little service, particularly considering the scope of The Need to Be Whole. One can be sympathetic to Berry’s frustrations with the language of professional historians, social scientists, and literary critics while also recognizing that “responsible language” sometimes necessitates the insights they can provide. Robert E. Lee might be a flawed, tragic figure, but he also emerged from a specific historical context and acted in history in certain ways that we are bound to confront if we truly want to understand him.

Similarly, Berry fails to use “responsible language” to discuss the removal of Confederate monuments. He baroquely describes the opposition to Confederate monuments as the perfect “large, symbolic, and monumental” gesture required by the desire for “score-settling.” “Now all of these [Confederate statues and monuments] have become eligible for some sort of deletion,” he writes.

And not only these, but also any public work of art that reminds black people that their ancestors were enslaved or that reminds white people that their ancestors (or other white people’s ancestors) did the enslaving. To be rid of such reminders presumably is to be rid of the pain of remembrance, which is the pain of the knowledge of history. By this symbolic destruction of the sinful past, the way presumably is opened for the arrival of the sinless future.

One can share Berry’s reticence to lose sight of the realities of our history while nevertheless asking if Confederate monuments are really the best vehicle for remembering and telling this story. These, after all, are not frescoes. Many of them were cheap, hollow cast-iron statues erected by the Daughters of the Confederacy across the South during the height of the Klan’s 1920s resurgence. “We need to take more care to remember that all statues, even statues of Confederate soldiers, were made by artists and are works of art,” he writes. This is both incorrect and a violation of Berry’s own encomiums regarding “responsible language.” That the effort to remove these monuments may be a belated and insufficient reckoning with the hidden wound he so eloquently describes elsewhere does not seem to cross his mind.

Berry is at his finest in The Need to Be Whole when discussing literature. His recollection of his long friendship with the black Louisianan novelist Ernest J. Gaines, and his discussion of Gaines’s novel A Gathering of Old Men, ranks among his finest writing anywhere. This novel, Berry writes, “has come to exemplify for me the right way . . . for a person to contribute to the good-faith conversation about our racial history and present race relations that is so urgently needed. It is the right way, I think, not because it speaks for a political side, but because it is supremely a work of imagination and therefore supremely a work of understanding and therefore of sympathy.” That Gaines is one of America’s great—and too-little discussed—novelists, and that imagination, understanding, and sympathy are sorely needed, are strong cases to be made. By the same token, one can wholeheartedly recognize the necessity of storytelling, literature, and honest conversation while recognizing that these tools are insufficient in achieving the greater understanding that Berry attempts but fails to achieve in The Need to Be Whole.

In the wake of the renewed racial unrest of 2020, University of Kentucky President Capilouto pledged to remove Ann Rice O’Hanlon’s fresco. Karyn Olivier expressed her opposition in a press release: “The university’s decision to remove the O’Hanlon mural also renders my work Witness blind and mute. It cannot exist without the past it sought to confront. And it is ironic that the decision to censor the original artwork has, in one fell swoop, censored my installation, too.” Separately, Berry and his wife Tanya filed a request in Franklin County Circuit Court for an injunction against the removal. Although op-eds and letters to the editor in the Herald-Leader predictably followed, things remained at a standstill until November of this year, when a video of a white UK student assaulting a black student dorm worker while spouting racist epithets went viral on social media. Capilouto again pledged to remove the fresco, saying, according to the Herald-Leader, “Following the removal and relocation of a controversial mural, [Memorial Hall] will be transformed as a space, particularly for our students, to celebrate diversity and inclusion on our campus.” While the bloodless PR-inflected verbiage of this statement surely lies far from Berry’s call for “responsible language,” the ugly event that precipitated it was yet another rupture of the hidden wound. The ultimate fate of the fresco remains to be seen.

Correction (December 30, 2022): As originally published, this article referred to Port Royal as the name of Wendell Berry’s fictional community; Port William is the fictional community based on his real-life home of Port Royal.