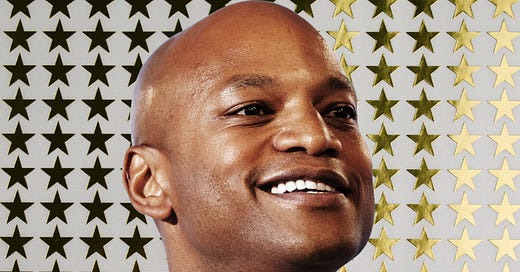

Can Wes Moore’s Progressive Patriotism Make Him a Democratic Star?

With an impressive resume—Army officer, Rhodes Scholar, bestselling author—the Democratic candidate for governor of Maryland talks of optimism and opportunity.

Baltimore Below the razor-wire fence that marks the outer perimeter of the Chesapeake Detention Facility, Wes Moore presses the flesh at an adjacent street fair run by Baltimore CONNECT, a local health-care-focused nonprofit. He walks among the pop-up tents and talks with men and women he hopes will support his bid for the governorship of Maryland. Campaign staffers occasionally peel away to take care of tasks resulting from his one-on-one conversations. One staffer reports being asked to find housing for a woman trying to leave an abusive marriage. Without experience in social work, the staffer isn’t sure where to start, as is often the case for members of the campaign who receive these directives from a boss with a palpable desire to show he can be of service.

Moore knows just how important assistance like this can be, and what can happen to those who don’t receive it: A dark, defining moment in his life came when, during his childhood, his own family was devastated following a bad encounter with the health care system.

Three weeks prior to this Baltimore event and just an hour south, Moore, 43, stood in front of a very different crowd as the warm-up act for Joe Biden. At a rally with the president inside the Washington Beltway, the politically hyper-engaged audience heard Moore deliver a message of opportunity, love of country, and respect for democracy. It’s a message that Democrats hope will resonate with the more affluent moderates—the Larry Hogan types who want politicians who share their values.

Moore’s unique selling proposition is that his candidacy and the message of progressive patriotism he is pitching might just win over both groups—the poorer voters who have long been loyal Democrats but are being targeted by the “populist” GOP, and the better-off suburban swing voters who are moving toward the Democratic camp but remain susceptible to backsliding. He presents this vision in both environments with equal swagger and skill. You might not guess that he’s new to the political game: Moore has a natural politician’s mien; his talent is so pronounced that even the longtime pros are jealous. His last Democratic predecessor in the governor’s office, Martin O’Malley, says of Moore that “in terms of connecting with peoples’ head[s] and their hearts, [he’s] probably the most skilled communicator that we've nominated in many years.”

Moore’s life experience supports the narrative he’s selling. He lost his father when he was 3 and got into petty crime as a teen; his family intervened, and afterward he got an associate’s degree, then a bachelor’s, and then a master’s as a Rhodes Scholar. He served in the Army, including a year-long deployment in Afghanistan, worked in government and banking and nonprofits, wrote some books, caught the eye of Oprah Winfrey, and decided to run for governor.

It’s a compelling story—so compelling that it lifted Moore to a Democratic gubernatorial primary victory, defeating pols with longer lists of bona fides and more prominent endorsers.

A dramatic win by a newcomer with Moore’s preternatural abilities is bound to seize the attention of Democratic partisans, who are continuing their “not ready to admit it’s desperate” nationwide search for a new-generation candidate—someone, anyone who can fill the void being left by the party’s gerontocratic Washington leadership.

Is Moore the one they are searching for? Is an outsider up to the task of running a big, complicated bureaucracy? Is the Baltimore striver’s story too good to be true?

For the candidate himself, the time to worry about speculative political gamesmanship is still a ways off.

First, he has to make his case outside the prison district.

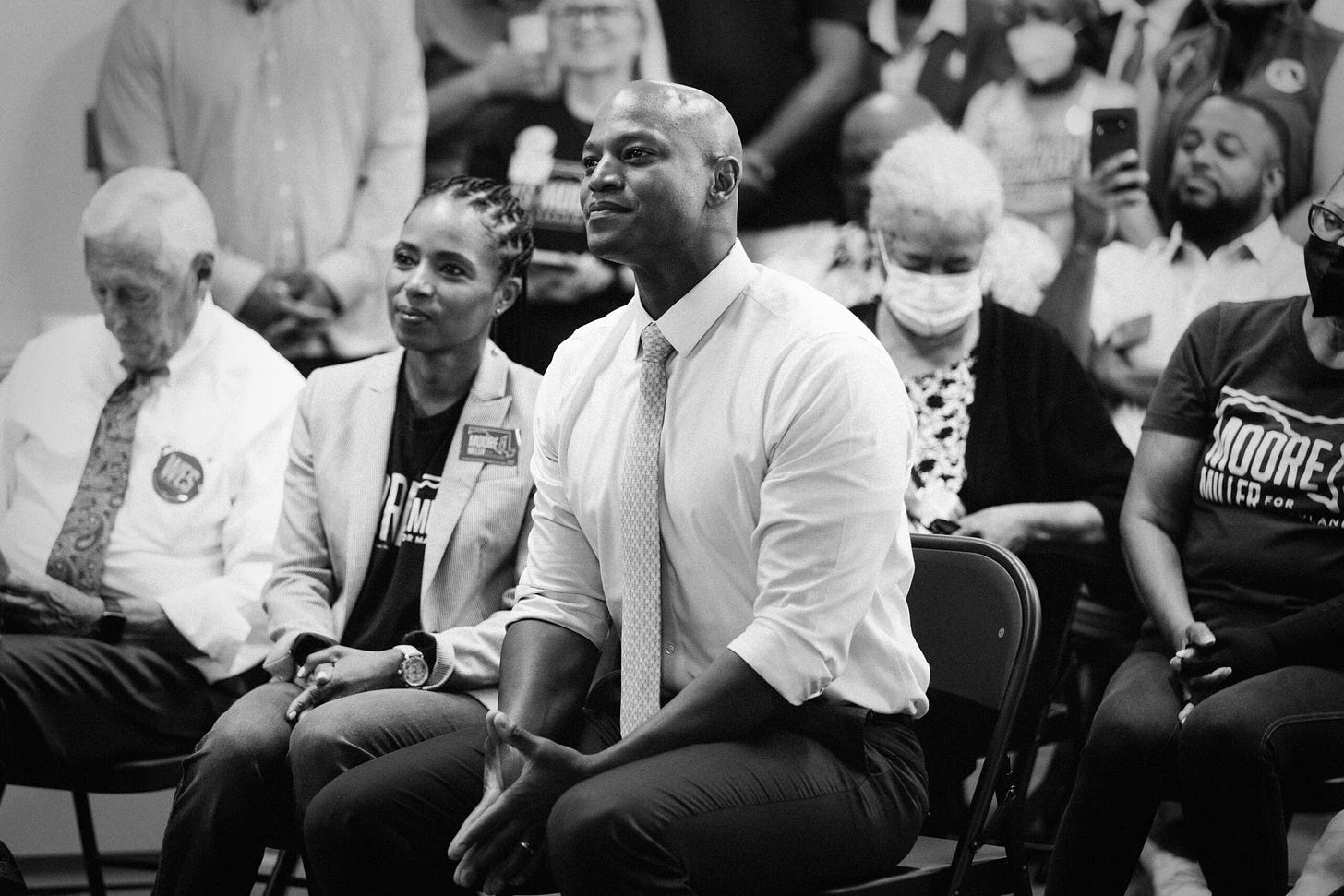

Wes Moore at the event outside the Chesapeake Detention Facility. (Photo by Hannah Yoest)

Making a visit to a community event like this—where local residents get connected to services that can prevent them from falling into long-term dependence on public assistance—is personal for Moore. As he writes in his books, he is acutely aware of the fact that, had his life taken a few different turns, he could have been the one in line for a government-subsidized phone or in pretrial detention on the other side of the razor wire. Instead, he is on track to become Maryland’s first black governor.

This awareness has influenced his message on the campaign trail. He adopted his slogan, “Leave No One Behind,” from his experiences in the 82nd Airborne. The line is a good summary of Moore’s priorities when it comes to representing voters who are facing economic hardship, who do feel left behind, and who at times sense that they are not important to the Democratic politicians who often take their votes for granted during election season.

We asked Moore what his message is for those voters. His starting point is his personal journey. “I know what their frustration is because I know what it’s like to struggle,” he said.

I know what it’s like to literally have my father go to a hospital and be turned away and not [get] the medical care he deserved. . . . You know, I know what it’s like to have my mom not get a job again with benefits until I was 14 years old. I mean, this is not academic to me. And so when you’re going to voters and you're going to working class voters, you can’t just go there with slick talking points, they're not gonna buy it. . . . You gotta be able to share your story, share your plans and share how it’s relevant to them in their lives.

The story that Moore alludes to involving his father is horrifying. A host for local radio station WMAL, the elder Wes Moore left work feeling ill one day in April 1982. He had trouble breathing. Tylenol did not help. After a sleepless night, he drove himself to the hospital but had difficulty communicating with doctors, who—as recounted in one of his son’s books—anesthetized his throat and instructed him to go home and “get some sleep.” Less than an hour and a half after he got back, he suffocated and collapsed at home. His epiglottitis—an infection of the tissue around the windpipe—could have been easily diagnosed and treated if he had not been handled so dismissively at the hospital. What’s worse, his death happened in front of his son. Wes was just 3 years old.

“That experience shaped Wes’[s] life and forged his view that health care is a basic human right,” his campaign’s one-pager on health care states.

After Moore’s father died, his mother, daughter of Jamaican immigrants, moved with young Wes and his two sisters to New York to live with his grandparents. They took out a second mortgage on their house to pay for his private schooling. Moore finished high school and got his associate’s degree. He tells loyal Democrats he is so proud of this that he wears his graduation ring to this day.

He also draws from his personal journey to reinforce the message that is becoming central to his campaign: In a contest between Moore and his opponent, Dan Cox—a Republican who was an active participant in the effort to overturn the 2020 election—Moore is the only patriotic choice.

Moore’s love of country is rooted in his family’s origin story. His great-grandfather initially moved the family from the Jim Crow South back to Jamaica. But as Moore tells it, his grandfather disagreed with his father’s decision: He didn’t want to be “run out” of the country where he was born. So he returned to America, went to an HBCU, and became a pastor—reportedly the first black pastor—in the Dutch Reformed Church, also known as the Reformed Church in America. Under its auspices, he ministered to a congregation in the country he had re-adopted and come to love in spite of the people who had terrorized his parents in its name.

Moore caught some of his grandfather’s love while coming of age in his home. His own education in patriotism continued in military school in Valley Forge and in his role as an officer in military intelligence in the Army. He kept at it as a White House fellow and low-level homeland security staffer working under Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice and Secretary of Homeland Security Tom Ridge.

(Photo by Hannah Yoest)

Moore told us this background undergirds his frustration with the MAGA Republicans. He drew a contrast with charlatans like Cox, a man who did not serve in the military, and does not even respect our democracy, yet still claims patriotism as a partisan value:

I see this idea and this concept of patriotism so bastardized. . . . For me, patriotism isn’t just an idea.

It’s actually . . . an action. You know, it’s a service, it’s defending our constitution. It’s believing in the hopes of this country, it’s fighting for every American, and you know, whether we agree or disagree. . . . I think of my life, my distance, my family, my journey, my sacrifice, and I’m deeply proud of the fact that I hold the title—and I raise the title—of patriot.

I know that it doesn’t belong to a party, but that it belongs to the people of this country—and particularly those who are leading in this country, and those who are willing to sacrifice for this country. And so it’s not just a core foundation of our campaign. It’s just been a core foundation of my entire life journey. Republicans have claimed the patriotism campaign theme since at least the Reagan era; Moore is committed to taking it back. He asks good questions: “What’s patriotic about storming the Capitol? And trying to overturn a democratic election? What’s patriotic about calling for the vice president to be [killed]?”

Cox was no mere half-hearted supporter of Donald Trump’s attempt to overturn the 2020 election. He even organized buses for people to get to Trump’s January 6th rally. Says Moore: “There will be no lectures coming from him, or any of that ilk, on what it means to be a patriot.”

Moore pairs his patriotism-as-service message with a policy recommendation. Should he become governor, he says, he wants to implement a program that would enable Maryland high school students to do a service-oriented gap year after graduation “in exchange for job training, mentorship, and other support including compensatory tuition at a state college or university.” Combining investment in education with a commitment to civic participation, this plan offers a fundamentally optimistic vision of the future—one that balances the welfare of individuals and the community.

If you find the point where service to one’s country intersects with “leave no one behind,” you’ve found the center of Moore’s agenda for Maryland in general and Baltimore in particular. While he left the city at a young age, he’s back now, grappling with how he can do right by those who didn’t “make it out” as he did.

This was the subject of a breakout New York Times bestseller titled The Other Wes Moore. Published in 2010, the book centers on another man with the same name and background, but whose life took a different course. That Wes Moore is in prison today—not while awaiting trial over the wall in Chesapeake, but in the correctional facility in Jessup, Maryland, half an hour to the south.

The idea for the book came to him in 2004. He had for four years been haunted by Baltimore Sun articles about another man named Wes Moore, a guy who was part of a jewelry-store robbery that went wrong, resulting in the killing of an off-duty police officer. This other Moore was serving a life sentence in Jessup.

Moore wrote him a letter—the start of a series of exchanges that became a yearslong correspondence, and the two Wes Moores eventually started talking face-to-face during prison visits, too. The Other Wes Moore is a biography and an autobiography, an attempt to understand how and why each man turned out as he did.

It’s a moving story, but one that isn’t without controversy. The other Wes Moore’s family has complained that the candidate has exaggerated his role in their son’s life and is cynically using him to further his campaign. The family of the slain police officer doesn’t like the publicity much better. Plus, opposing campaigns have accused Moore, who was born in Takoma Park but later attended college in Baltimore, of embellishing his connection to the neighborhood where the other Wes Moore grew up.

Candidate Moore has pushed back against these critiques: “I was clear in my book about where I was born, and also when I left. On page 37, I talked about when I left to go to New York to stay with my grandparents,” he said. “I came back to Baltimore . . . when I was in college.”

While much of Moore’s top-level messaging targets Cox and the MAGA threat, Moore’s experience as founder of BridgeEDU and CEO of the Robin Hood Foundation have informed an agenda that zags from the platform of the party’s left flank. To hear him talk about economic issues is to be put in the mind of Obama-era opportunity Democrats, arguing for policies that spur economic growth while sprinkling the appeal with a dash of hopey-changey unity rhetoric.

As a candidate, Moore is more comfortable talking about innovation and creating opportunity than he is hitting the high notes of class warfare currently in vogue thanks to people like Bernie Sanders, AOC, and Elizabeth Warren. Moore talks about balancing “competition” with being “equitable,” and he riffs on how Maryland can be a place of “entrepreneurship” and “innovation.” He said his role models among current governors are purple-state reformers Jared Polis of Colorado and Roy Cooper of North Carolina.

Far from planning a radical overhaul of the state government, Moore is instead committing to prioritizing “business and talent recruitment,” working toward clean energy and better emissions standards, and lowering prescription drug prices. (Although Moore affirms the idea that “health care is a human right,” a single-payer health system for the state is not one of his express policy goals.)

(Photo by Hannah Yoest)

Moore has also cited public safety as a potential area for building bridges with conservatives and others: “We can have a policing force—[one] that moves with appropriate intensity and absolute integrity and full accountability, and . . . our coalition consists of everyone from progressive Marylanders to the Fraternal Order of Police.”

Some local Republicans we talked to expressed skepticism that Moore will follow through on his promise to bring a moderate spirit to governance and will have the resolve necessary to resist being pushed around by a liberal, California-esque state legislature. O’Malley gave us a different view: There is an opportunity for a “governing consensus,” he argued, and Moore might have leeway to pursue a more results-oriented approach on issues like education and crime as an outsider coming off a big victory—and if his current lead holds, he will be on track to win by a huge margin.

How Moore will navigate state legislative politics and potential conflicts as governor remains to be seen, but on the campaign trail, at least, he has offered open arms to moderate Republicans who want to get on board:

I believe Larry Hogan is a patriot . . . I believe that while we don't agree on everything, and while we have some policy distinctions . . . our coalition actually includes Republicans and folks who are supporters of Larry Hogan.

Maryland’s Republican governor didn’t quite share the warm feelings. On CBS recently, Hogan said he was “not endorsing anybody in the race” despite calling Dan Cox, Moore’s opponent, “mentally unstable.” You’d think the easy call for Hogan would be to support Moore. But we might be in for a replay of 2020, when Hogan, perfectly aware of the Trump threat, made a show of writing in Ronald Reagan instead of casting a ballot for Joe Biden.

While Hogan acts as if he’s above the politics of it all, Moore doesn’t have that option. Before he can start navigating statehouse politics in Annapolis or fielding the inevitable calls from the Sunday shows, he still has to take care of business against his insurrectionist opponent. Moore's only debate with Cox will be on Maryland Public Television on October 12.

(Photo by Hannah Yoest)

As Moore walks to an SUV outside the detention facility with a private security guard, he pauses to chat with The Bulwark. We brought along a library copy of the young adult adaptation of his first bestselling book. He chuckles; it’s been nearly ten years since this version was published. When we asked Maryland’s likely future governor to write an inscription in it—something to delight the next person to take out the book—Moore wrote: “Keep Leading! Elevate.”

It’s as much a message for himself as for them.

Correction (27 September 2022, 1:45 p.m. EDT): As originally published, this article stated that Moore pulled out of a second debate with Cox. The Moore campaign says they had not agreed to a second debate with Cox.