If Trump Wasn’t Lying, That’s Worse

A delusional president is far more dangerous than a mendacious one.

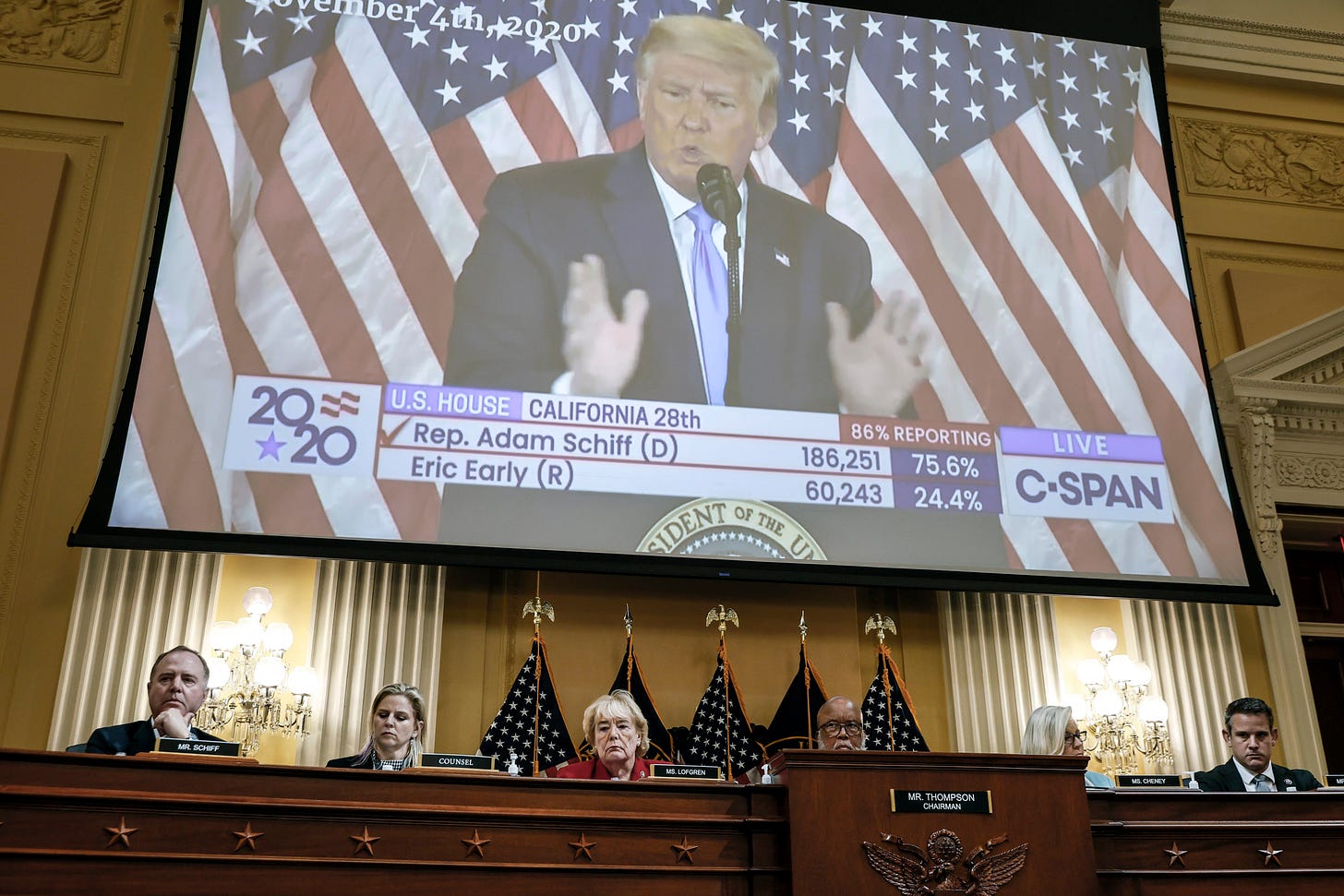

On Monday, the House January 6th Committee presented evidence that Donald Trump, after losing the 2020 election, promoted allegations of voter fraud that his own advisers had told him were false. According to the committee, this evidence proves he was lying.

But the evidence actually points to a different conclusion: Trump wasn’t lying in the way that other presidents have done. He was simply impervious. He refused to accept unwelcome facts. And that degree of imperviousness, in a president, is much more dangerous than dishonesty.

Testimony at Monday’s hearing showed that many people around Trump—Mark Meadows, Jared Kushner, Ivanka Trump, and others—knew his claims were false. But the testimony about Trump himself was different. Nobody recalled the then-president privately admitting, in the style of Richard Nixon, that he was hiding the truth. Instead, everyone who had interacted with Trump described him as batting away information he didn’t want to hear.

Exhibit A: Trump’s statements before the election.

A video reel compiled by the committee showed Trump stipulating—months before November 2020—that if he lost, fraud was the only possible explanation. One clip showed him saying on Aug. 17, 2020: “The only way we’re going to lose this election is if the election is rigged.” Another showed him in a debate on Sept. 29, 2020: “This is going to be a fraud like you’ve never seen. . . . This is not going to end well.”

Rep. Zoe Lofgren, a member of the committee, summarized Trump’s mentality: He had “decided even before the election that regardless of the facts and the truth, if he lost the election, he would claim it was rigged.” No evidence to the contrary could shake his conviction.

Exhibit B: Election night.

In video testimony, Bill Stepien, Trump’s 2020 campaign manager, told the committee that on Election Night, he had advised Trump that “it was too early” to know who had won and that Trump shouldn’t claim victory. “The president disagreed with that,” Stepien recalled. “He thought I was wrong. He told me so and [that] he was going to go in a different direction.” Trump then went on TV and told the public: “Frankly, we did win this election.”

Trump had been warned before the election that because Democrats were more likely than Republicans to vote absentee, he would lose ground in key states as mail ballots were counted. In claiming victory, he defied that warning. But even in private, he expressed his defiance as belief, not deceit: He thought I was wrong.

Exhibit C: Trump’s rejection of “Team Normal.”

Stepien recalled the Trump campaign’s investigation of a claim that thousands of illegal immigrants had voted in Arizona. The campaign’s lawyers found that the claim was false.

At the hearing, Lofgren explained what happened next: “When these findings were passed up the chain to President Trump, he became frustrated, and he replaced the campaign’s legal team.” Lofgren played video of Stepien’s testimony, in which he described how the campaign’s lawyers, having given Trump findings he didn’t want to hear, were “moved out” and replaced by Rudy Giuliani and others who told Trump what he did want to hear.

Exhibit D: The Trump-Barr breakup.

On Dec. 1, 2020, then-Attorney General Bill Barr told the Associated Press that he had seen no evidence of fraud sufficient to cast doubt on Joe Biden’s victory. Later that day, Trump called Barr into the Oval Office and raged at him. In video testimony aired on Monday, Barr recalled the president telling him, “You must have said this because you hate Trump.” Barr testified that in the meeting, he refuted Trump’s fraud allegations point by point, calling them “bullshit,” “idiotic,” and “crazy.” But in a video released the next day, Dec. 2, Trump repeated the allegations Barr had just debunked.

Again, there’s no sign of Trump grappling with the facts presented to him. Instead, in a narcissistic reflex, he dismissed them as an expression of hostility: You hate Trump.

Exhibit E: Trump’s conversation with Rich Donoghue.

Donoghue, who served as acting deputy attorney general during the post-election crisis, testified on video about a conversation in which he had guided Trump through the bogus allegations the then-president was promoting. This conversation provides the strongest evidence that Trump knew he was spreading lies. But it also shows how easily and rapidly he shifted his mental defenses to maintain the myth of massive fraud.

In the conversation, which took place some time after the election (the date wasn’t specified), Donoghue refuted Trump’s claim of a high error rate in mechanical counting of ballots in Michigan. According to Donoghue’s testimony, “The president accepted that. He said, ‘OK, fine. But what about the others?’”

So Donoghue proceeded to the next allegation: that a truck driver had transported rigged ballots from New York to Pennsylvania. Donoghue told Trump that federal investigators had looked into the truck’s loading and unloading and that their findings didn’t support the allegation. Donoghue says Trump didn’t press him on this point: “Again, he said, ‘OK. . . . What about the others?’”

Next, Donoghue proceeded to allegations about a ballot-stuffed suitcase and multiple scanning of ballots in Georgia. He explained to Trump that video evidence contradicted the allegations. Again, Trump responded by moving on: “Then he went off on double voting . . . He said, ‘Dead people are voting. Indians are getting paid to vote.’”

In the face of Donoghue’s refutations, Trump kept retreating: OK, fine. But the retreats were just tactical. Trump was committed to his belief in massive fraud, and he was determined to find a story—the trucker, the suitcase, whatever—to justify that belief. As Donoghue explained to the committee: “There were so many of these allegations that when you gave him a very direct answer on one of them, he wouldn’t fight us on it, but he would move to another allegation.”

If Trump truly believed, despite all evidence, that the election was stolen, that might buy him some relief from criminal charges that require corrupt intent. But in terms of his fitness for office, the theory that he was deluded—not lying—is more alarming, not less.

In his testimony, Barr described a meeting with Trump on Dec. 14, 2020. Trump was still ranting about Dominion and other fantastic tales. “I was somewhat demoralized,” Barr told the committee, “because I thought, boy, if he really believes this stuff . . . he’s become detached from reality.” Barr speculated that Trump had “lost contact.” He recalled that each time he told Trump “how crazy some of these allegations were,” Trump brushed aside the information: “There was never an indication of interest in what the actual facts were.”

“I felt that before the election it was possible to talk sense to the president,” Barr testified. This sometimes required “a big wrestling match” with Trump, he explained, but “it was possible to keep things on track.” But “after the election, he didn’t seem to be listening.”

Detached from reality. Lost contact. No interest in facts.

We can’t have a president who thinks—or doesn’t think—this way. We can’t put the world’s most powerful armed forces and nuclear arsenal back in the hands of a man who believes, no matter what, that he has the mandate of the people—and is willing to use violence to stay in power. In the Oval Office, a madman is far more dangerous than a liar.