What Mike Pompeo Leaves Out

In a memoir clearly intended to prepare for a presidential run, the former secretary of state toots his own horn—but his silences are louder.

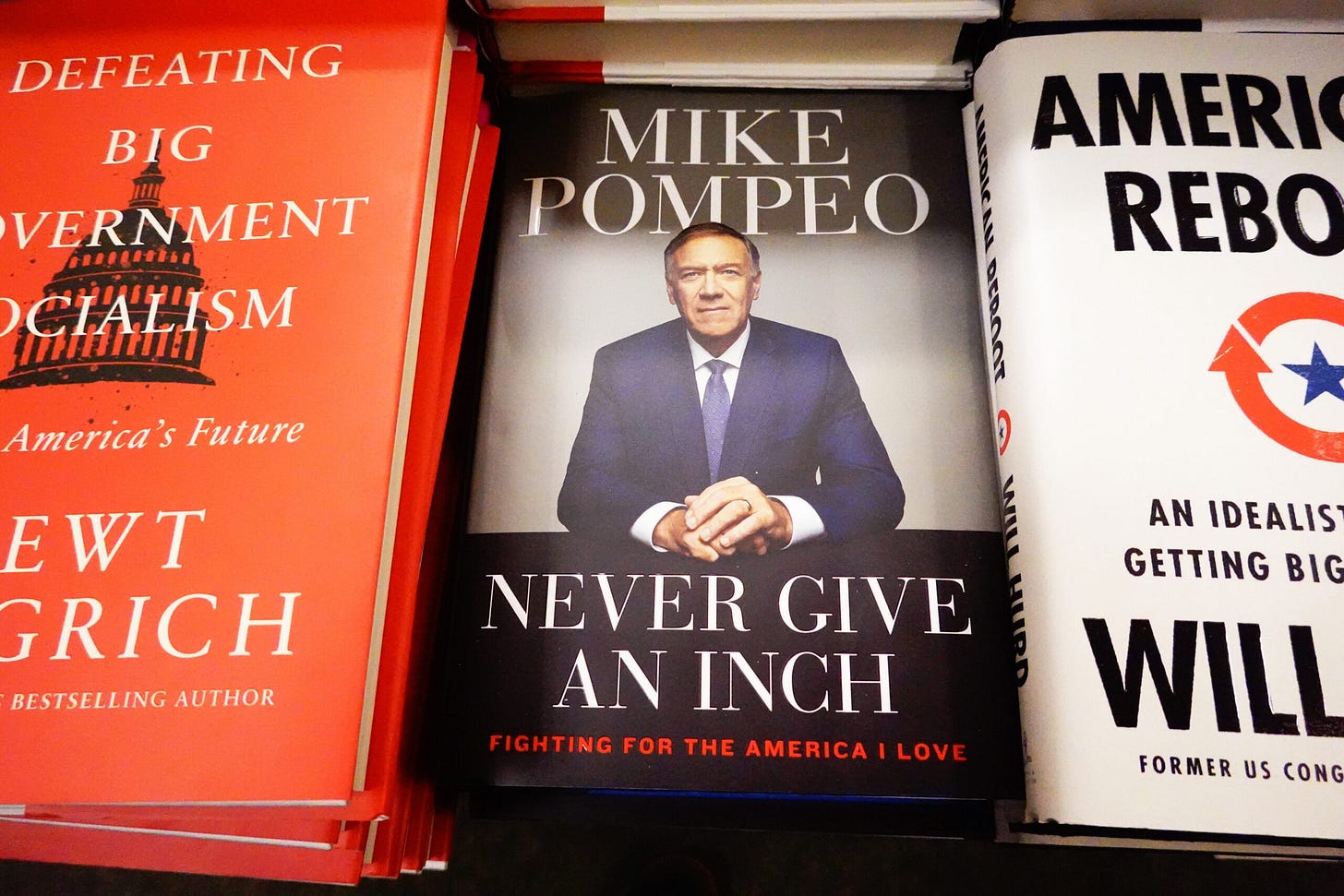

“My Mike” was the nickname that President Trump bestowed on Mike Pompeo, who served first as his CIA director and then as his secretary of state. The appellation was fitting, for among Trump cabinet appointees no one was more faithful to the boss. As Pompeo notes in his new memoir, Never Give an Inch, while his peers were being dismissed by tweet, he prospered and thrived. “In the end,” Pompeo writes, “I was the only member of the president’s core national security team who made it through four years without resigning or getting fired.”

Now Pompeo appears to be preparing for a presidential run himself. To that end, he has produced a volume that sets the stage for the campaign, rehearsing the accomplishments of his term in government, offering maxims for leadership, and projecting an image that combines ostentatious Christian piety with profanity-spewing alpha toughness. He hopes this will propel him to the Republican nomination and, beyond that, the White House.

Pompeo’s path to power began with an education at West Point, where he was first in his class. After five years of service in the Army as a cavalry officer, he went on to Harvard Law School, then a career in law, and then a stint in business. In 2010, he successfully ran for Congress, where he served for three terms. He had won a fourth in 2016, but only days later, President-elect Donald Trump tapped him to be CIA director.

The agency, in Pompeo’s telling, had become risk averse during the Obama years under the leadership of John Brennan, who is characterized here as “a total disaster.” Pompeo saw his task as rebuilding the agency’s morale and preparing it for risky jobs. Initiatives were set in motion to break from “past failures,” with President Trump granting the agency additional authority to, in Pompeo’s words, “give top jihadi leaders their death wish more quickly.” Pompeo also worked to recement ties with Israel’s Mossad, establish the Iran Mission Center to counter Iran’s nuclear threat, and, at Trump’s direction, create a channel for talks with North Korea.

Just as he was getting into gear at the agency in the summer of 2017, Rex Tillerson, Trump’s first secretary of state, called the president “a fucking moron,” or so it was reported. Several politically fraught months later, the former Exxon CEO was out the door, and Pompeo was asked to fill the empty slot.

Following contentious confirmation hearings, a raft of foreign policy issues immediately floated toward him. Among them: pushing NATO allies to spend more on defense, breaking out of the nuclear arms agreement with Iran, disarming nuclear-armed North Korea, reviving ties with both Israel and Saudi Arabia, confronting Putin’s Russia, and turning the ship of state’s rudder hard against Communist China.

Pompeo deserves credit for several real accomplishments. Some of the initiatives he championed, like fundamentally altering the terms of our relationship with Beijing, were both necessary and overdue. Taking out the Iranian warlord Qassem Soleimani, a gutsy step that drew fierce criticism from liberals, looks in retrospect to have been a successful gamble, a bold assertion of American power that dealt a serious blow to the Islamist regime. Fostering the Abraham Accords between Israel and the Gulf states (where Jared Kushner and U.S. ambassador to Israel David Friedman played the leading roles) deserves hearty applause.

But along with success on some central issues, there was a lot of failure, and a great deal of it stemmed not from Pompeo’s ineptitude, but the peculiar character of the president he devoted his considerable intelligence and energy to serve. Crowing about his successes, Pompeo says unsurprisingly little about the discomfiture of working at the behest of Donald Trump. But the little he does say is both disingenuous and revealing.

One of Pompeo’s first ideas in his first role in the administration was that the newly inaugurated Trump should make an early appearance at the CIA headquarters to show the world that the president—who had just compared U.S. intelligence officials to Nazis—did not hate the agency and that the CIA was “back.” So, on his first full day in office, Trump came to Langley, where he made a spectacle of himself in front of the CIA’s memorial to its fallen officers with a bragging, meandering rant about the crowd size at his inauguration. All that Pompeo says about the episode is that President Trump “treated the event a bit too much like one of his campaign rallies.” Yet all in all, Pompeo opines, it “was incredibly productive for America and our team.” Rubbish. The speech was both bizarre and a disgrace. (The text of the entire speech remains essential reading, a preview of much that was to come.)

There is a great deal of such unconvincing spin in Pompeo’s book. And there is a great deal of failure dressed up as success. Diplomacy with North Korea’s absolute dictator, Kim Jong-un, is a case in point.

Pompeo speaks of how “we vowed to avenge” the murder of Otto Warmbier, the young American college student who had been taken captive in Pyongyang in early 2016, apparently tortured, and returned to his parents the following year in a coma from which he would never wake. But the administration did nothing of the kind. To the contrary, Trump absolved Kim of the crime. “He tells me,” said Trump of Kim following one of their summits, “that he didn’t know about it and I will take him at his word,” adding that in fact Kim “felt badly about it. He felt very badly.” About this appalling whitewash, Pompeo says not a word.

Then there was the violent language Trump employed, warning that North Korean threats against the United States would be “met with fire and fury like the world has never seen.” Writes Pompeo, “I thought the strategy of matching Kim’s incendiary rhetoric was brilliant. No other administration would ever have done this.” This last sentence was true, but what Pompeo entirely neglects to mention is the fawning language Trump also directed at the tyrant, exalting him for sending “beautiful letters,” so beautiful in fact that “we fell in love.” Not brilliant. And no other administration would have done that, either.

What did such extravagant diplomacy achieve? About one of his visits to the Hermit Kingdom, Pompeo writes that Kim “committed to completely getting rid of his nuclear weapons, saying that they were a massive economic burden and made his nation a pariah in the eyes of the world.” But despite two presidential summits, the commitment was not honored, and it was Kim Jong-un who never gave an inch. All that was accomplished was the elevation of the North Korean dictator from outcast to global statesman. Trump’s claim, following his summit with Kim in Singapore, that “there is no longer a nuclear threat from North Korea,” was either a delusion or a lie, and if the latter, one of thousands.

Pompeo has gotten a bit—but only a bit—of a bum rap for downplaying the murder of Jamal Khashoggi by Saudi Arabian intelligence operatives. After all, he does say of the crime that the killing and subsequent dismemberment of the Washington Post journalist was “outrageous, unacceptable, horrific, sad, despicable, evil, brutish, and of course, unlawful.” But without reservation, he extols the leader behind the crime, Mohammed bin Salman, the crown prince of Saudi Arabia, as “one of the most important leaders of his time, a truly historic figure on the world stage.” Even worse, he heaps praise on the Saudi agency responsible for the killing, writing, “I . . . had the occasion to meet with my former counterparts in the Saudi intelligence services—great guys who understood the dark world of espionage and how to operate in it.” Great guys? This is perverted.

Is it campaign strategy or genuine conviction that leads Pompeo to position himself as a fierce culture warrior against an “establishment [that] too often loathes the citizens it purports to represent and seeks to destroy our nation’s Judeo-Christian founding”? In this and similar lines, the book’s authorial persona, which awkwardly mixes piety and belligerence, comes to the fore. In addition to immoderately salting his prose with references to the “good Lord” and to “His grace,” Pompeo uses a great deal of crude rhetoric in his book. While praising the Saudi intelligence operatives to the skies, we find Hillary Clinton aide Susan Rice described as Clinton’s “henchwoman.” Barack Obama’s nuclear deal with Iran may have been dangerously misguided (as I believe it was), but was it “staggeringly stupid”? The Foreign Service Officer Corps may be liberal in its orientation, but is it really “overwhelmingly hard left in its cultural sympathies”? Pompeo makes it sound as if his State Department underlings were members of Antifa. Like his former boss, Pompeo evidently lacks a subtlety gene.

As the Trump administration drew to its ignominious end, Pompeo also contributed his bit to the great election lie. On November 10, 2020, days after Trump was defeated at the polls, Pompeo pronounced that “there will be a smooth transition to a second Trump administration.” In Never Give an Inch, he explains this away as having “a bit of fun,” with the reality being that “there was still ongoing litigation, and the president had every right to ensure that that the election had been conducted in a fair and lawful manner.” Disingenuousness yet again. His book offers not a word of criticism—or any discussion at all—of Trump’s conspiracy to cling to office in defiance of the electorate’s will.

There is a great deal of such sidestepping going on. Across four years of service in the Trump administration and yet again in this memoir, Pompeo has amply earned the former president’s nickname for him of “My Mike.” Whether clinging so tightly to the man from Mar-a-Lago will work as an electoral strategy in 2024 remains to be seen.