[On the October 7, 2022 episode of The Bulwark’s “Beg to Differ” podcast, guest Steve Vladeck discussed the Supreme Court and Voting Rights Act.]

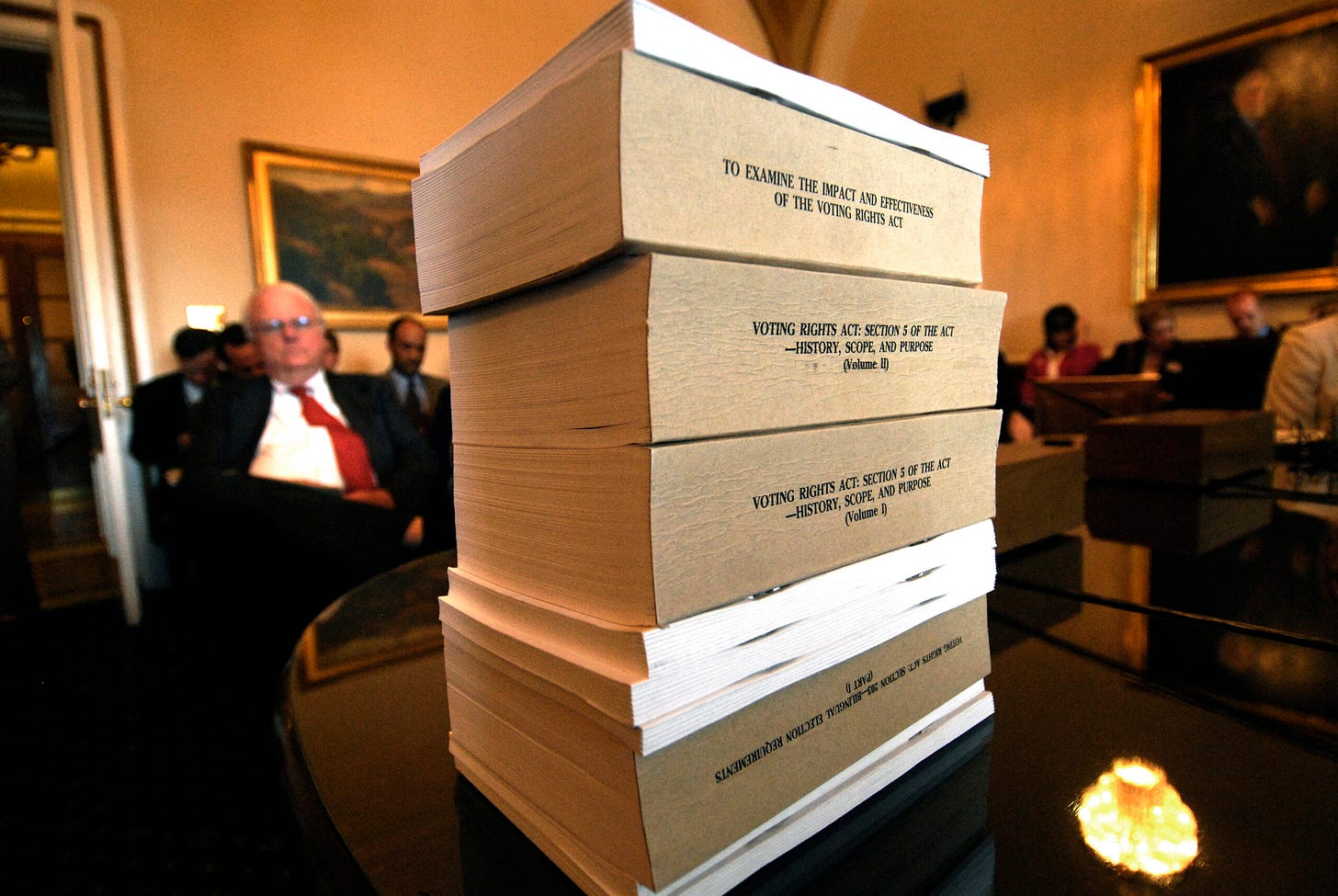

Steve Vladek: It’s not just the affirmative action cases this term that have the Supreme Court in the middle of a national racial debate. The redistricting cases in Alabama are basically about the centerpiece of the Voting Rights Act—section two—and whether Congress has the ability to require states to draw so called “majority minority” districts, that is to say, to have districts that are somehow reflective of the diverse breakdown of a state. Alabama, about 28 percent of its population is black. Black Alabamians live in compact areas, which under the Supreme Court’s precedents mean they are entitled to representative proportional apportionment in Congress, and Alabama drew a map that actually only has one district that would cover the black population. A three-judge district court with two Trump appointees said that this violates the Voting Rights Act. The Supreme Court blocked that decision with no explanation, allowing Alabama to use unlawful maps. . . .

Mona Charen: Steve, can I interrupt just to ask a clarifying question for me. . . . The state of Alabama is arguing that if they had created a second majority black district, that it would violate the Constitution’s Fourteenth Amendment and Fifteenth Amendment, because it would have required them to take race into account and to draw a specifically racial district. But does the Voting Rights Act demand that? I’m a little confused about that. . . .

Vladek: The Voting Rights Act, as it has been interpreted by the Supreme Court in a series of cases, most prominently a 1986 case called Gingles, does, in fact, require legislatures to take into account the sort of packing of districts, the representativeness of minority populations in a state, including racial minorities, for the purpose, Mona, of preventing discrimination on the basis of race.

So the argument is that, right, what Alabama is proposing is not neutral. The map Alabama proposed, according to the district court, discriminated against black Alabamians by only having one seat in the congressional delegation that would represent out of seven . . . that would represent a population that was more than two-sevenths of the state population. . . .

Here, unlike in the affirmative action cases, where we have moved away from the argument that the racial preferences are a response to racial discrimination, here, there’s a direct connection. Here, the argument is that Alabama is required to draw a second majority-minority district because to not draw that district is to discriminate on the basis of race as the Voting Rights Act has defined that. . . .

What is remarkable about this case is not just that it really brings to full froth, right . . . whether the centerpiece of the civil rights movement, the Voting Rights Act, is itself unconstitutional by creating these race-infused rules. But it also I think, really drives home how much the Supreme Court has injected itself into the midterms. Because based on the February emergency ruling on the shadow docket in the Alabama case, a ruling in June in a Louisiana case and how lower courts have interpreted those rulings, Mona—there are as many as ten House seats that are going to be safe Republican seats in the midterms, that had these lower court rulings not been affected or blocked by the Supreme Court would almost certainly have been safe democratic seats. I think it reinforces both how much race is hanging over this entire Supreme Court term, and how invested the court has become for better or for worse, really, in what may be who controls the House come January 2023.