Where’s the Chief?

John Roberts should be presiding over the Senate’s second Trump impeachment trial.

While Republicans howl at the supposed unconstitutionality of the second impeachment of Donald J. Trump—with only five Republican senators joining Democrats to defeat an attempt to dismiss the charge of incitement of insurrection on the grounds that only presidents who successfully overthrow an election and secure a second term can be impeached—the chief justice of the United States has bowed out of the impeachment business altogether. This is puzzling, to say the least.

Equally puzzling is the Democrats’ supine willingness to accommodate John Roberts’s “out to lunch” demand. It has fueled the feigned outrage that this impeachment effort is just another partisan political attack on Donald Trump rather than a legitimate attempt to hold him accountable for provoking the Jan. 6 mob attack on the Capitol that left five people dead.

Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-N.Y.) told MSNBC’s Rachel Maddow on Monday that Chief Justice Roberts “did not want” to take part in the second impeachment trial. Senate president pro tempore Patrick Leahy (D-Vt.) is presiding over the trial instead.

Keep in mind that the conservative 6-3 majority on the Supreme Court is stacked with professed textualists, including Justice Amy Coney Barrett who explained at her confirmation hearing: “In English that means that I interpret the Constitution as a law, that I interpret its text as text, and I understand it to have the meaning that it had at the time people ratified it. So that meaning doesn’t change over time and it’s not up to me to update it or infuse my own policy views into it.”

Article I, Section 3 states: “When the President of the United States is tried, the Chief Justice shall preside.” Remarkably, this is the only mention of the office of chief justice in the Constitution, a fact that speaks to the importance of this responsibility of the office.

Reading between the lines, Roberts’s argument for standing down is that the Constitution uses the present tense: “When the President is tried.” Joe Biden is now president; Donald Trump is an ex-president; therefore, Roberts has no constitutional obligation to serve. Some distinguished legal and constitutional scholars, such as former solicitors general Paul Clement and Neal Katyal, have indicated agreement with Roberts.

The problem with this argument is multifold. First, let’s dispense with Senate Republicans’ claim that impeaching a former officeholder is unconstitutional. It is far from clear that trials of ex-presidents are unconstitutional, particularly as the Senate has once before held an impeachment trial for an official after he left office. And while scholarship is mixed on the question, logic would seem to suggest that trials and convictions of former officials—especially officials who were impeached while they were still in office—are constitutional.

Second, Roberts is one of nine justices whose jurisdiction is confined to cases and controversies properly before the Court under Article III—he has no unilateral constitutional authority to interpret the Constitution’s language. Even if the question of Article I, Section 3’s meaning were put before full Court, it could not issue what are known as advisory opinions. Cases must emerge through the jurisdictional confines of Article III and its enabling legislation, lest courts start doing the business of the political branches.

Third, Roberts’s decision to absent himself from the Senate trial has stoked the flames of partisanship—not quelled them. Sen. Rand Paul (R-Ky.)—who moved unsuccessfully to dismiss the impeachment article as unconstitutionally too tardy for a trial—has argued that “If the chief justice doesn’t preside, I think it’s an illegitimate hearing and really goes to show that it’s not really constitutional to impeach someone who’s not president.”

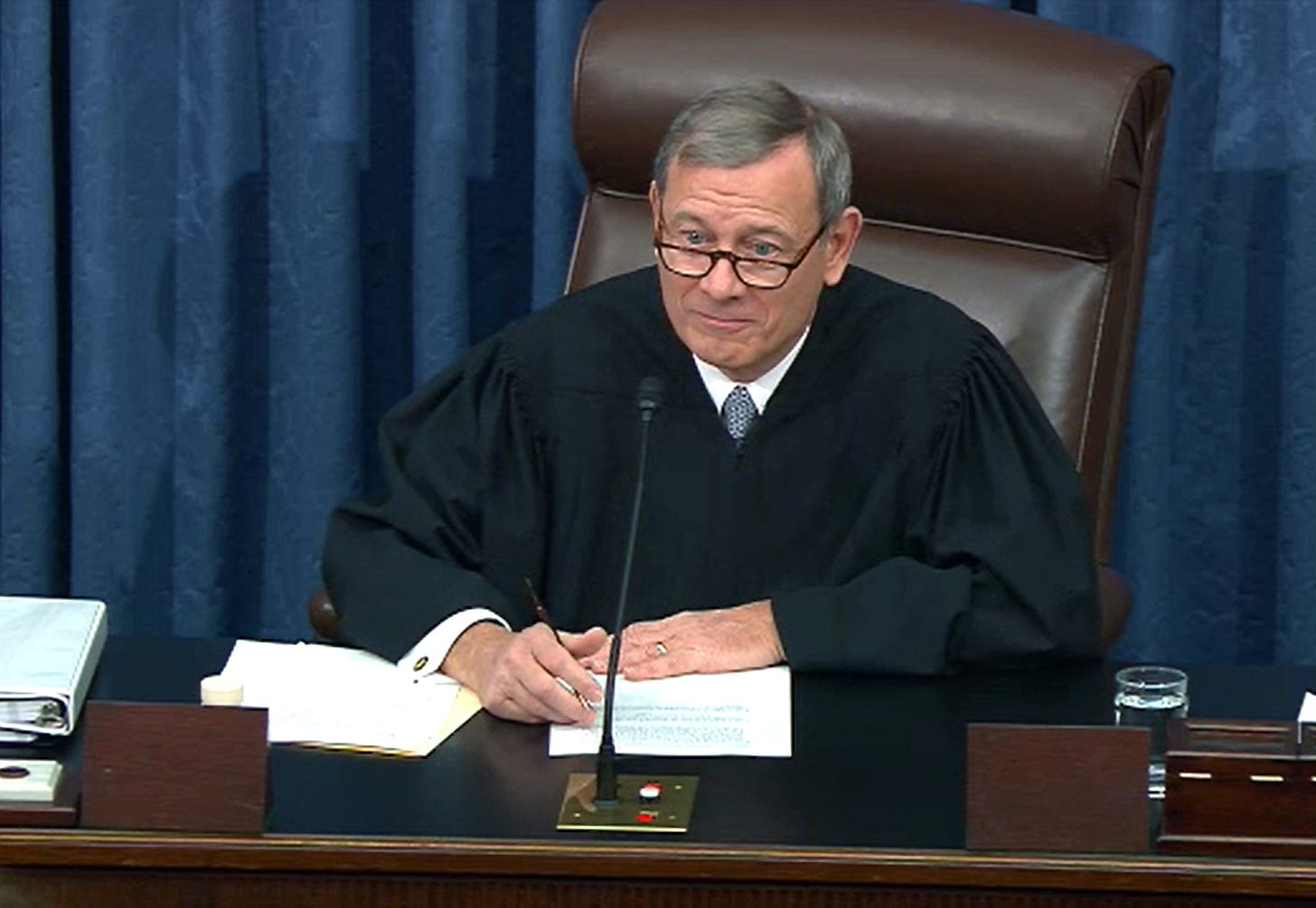

Chief Justice John Roberts presiding over President Donald Trump’s first impeachment trial in early 2020. (Photo by Senate Television via Getty Images)

Assuming for the sake of argument that the question of who must preside over an impeachment trial of an ex-president were properly before the full Supreme Court, and assuming further that a majority were to agree with legal scholars that the question has no easy answer, then conservative justices would presumably look—as Justice Coney Barrett explained—to the intention of the Framers of the constitutional text.

A number of delegates to the Constitutional Convention (including James Madison) argued that the judiciary should conduct impeachments. After a motion by Gouverneur Morris of Pennsylvania to table the issue, what eventually prevailed was a process that gave the Senate the power to try impeachments. In Federalist No. 65, Alexander Hamilton defended the choice as avoiding “double prosecution” if a court were to preside over an impeachment trial and a criminal trial of the same person.

Under the Constitution’s plain text, the role of the chief justice is unique to presidential impeachments; when federal judges and other “civil officers” are impeached, the president of the Senate (that is, the vice president of the United States) or the president pro tempore presides. Scholars have long reasoned that having the chief justice oversee presidential impeachments “is a device for avoiding the prejudicial effect of a conflict of interest,” since the vice president and the president pro tempore are both in the line of succession. With Trump now out of office, the line of succession upon removal of a president is not a concern.

But there other concerns that counsel against the chief justice’s absence on Feb. 9, the date now set for the start of the trial.

Preceding debate over whether to impeach President Richard Nixon, the House Judiciary Committee in Feb. 1974 issued a report on the inevitable ambiguities in the constitutional text. Its conclusions bear repeating:

The framers understood quite clearly that the constitutional system they were creating must include some ultimate check on the conduct of the executive, particularly as they came to reject the suggested plural executive. While insistent that balance between the executive and legislative branches be maintained so that the executive would not become the creature of the legislature, dismissible at its will, the framers also recognized that some means would be needed to deal with excesses by the executive. Impeachment was familiar to them. They understood its essential constitutional functions. . . . The emphasis has been on the significant effects of the conduct—undermining the integrity of office, disregard of constitutional duties and oath of office, arrogation of power, abuse of the governmental process, adverse impact on the system of government.

The chief justice of the United States should likewise adhere to this vision of the immense importance of the role of impeachment in our constitutional system rather than leave the process entirely to the politicians, based on what seem like textual gymnastics. (The Supreme Court has declined to comment on Roberts’s decision.)

Sen. Leahy is hardly unbiased, having voted to convict Trump the first time around. The lack of bias—or even the appearance of bias—is precisely why federal judges have lifetime appointments devoid of the pressures of re-election. Both parties in Congress, along with the chief justice, have assisted in a cheapening of a hallowed lever of presidential accountability. Once again, it’s the people who lose.