The contrast between Elizabeth Warren and Joe Biden is stark: Biden is comfort food; Warren is food for thought with, to some tastes, a dollop of spinach.

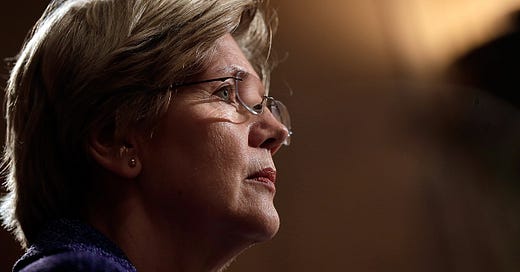

Warren stands virtually alone in the field by offering comprehensive, and specific, proposals for reanimating American democracy by reforming capitalism to reconcile its long-term interests with the needs of Americans writ large. She is, in substantive terms, by far the most important Democrat seeking the presidency.

Whether one tends right or left, Warren's importance to the political dialogue transcends the eventual fate of her campaign. That’s because she is asking an essential question: Can we repair our deepening economic and social fissures by making large corporations more responsive participants in a revitalized democracy which expands economic opportunity, reinvigorates competition, and redefines corporate citizenship. Her candidacy is an attempt to rescue contemporary capitalism from its potentially fatal excesses.

To attempt this, Warren takes two broad pathways. The first reimagines the traditional Democrats’ curative of aggressive federal spending to equalize opportunity by lowering the barriers to advancement facing average Americans. The second would recast Warren as Teddy Roosevelt reincarnate: a rigorous regulator who would make the marketplace more accessible, and democracy more inclusive, by curbing the accretion of corporate power.

In contrast to the array of candidates who propose to banish Donald Trump by channeling outrage or inspiring hope—or, in the case of Bernie Sanders, conjuring a fantastical "political revolution"—Warren offers specific proposals to define our future. Says David Brooks: "I might agree or disagree with some of Elizabeth Warren's zillions of policy proposals, but at least they're proposals. At least they are attempts to ground our politics in real situations with actual plans, not just overwrought bellowing about the monster in the closet."

By her own account, Warren's worldview derives from her own experiences. "I want to fix the systems in this country," she says, "so they work for Americans, not just for giant corporations or Big Pharma or the Goldman Sachs guys. That's not just my political career. That's my whole life."

To an uncommon degree, biography—from Warren's modest beginnings through her unplanned transition from academic to late-life politician—seems central to assessing her policy prescriptions. She was born in Oklahoma to a struggling middle-class family that was nearly derailed by her father's heart attack. Their car was repossessed; foreclosure loomed; her mother went to work; at 13 Warren began waiting tables. Unable to afford college, Warren attended George Washington on a debate scholarship. She married young, finished law school while juggling childcare, then worked from home until a beneficent aunt moved in.

As an academic, her research focused on the causes of middle–class bankruptcy. Contradicting her original assumptions, she concluded that in most cases the principal cause is not profligate spending, but medical emergencies, random misfortune, and families stretching to advance to buying homes in better school districts. This led to her first engagement with high stakes politics: opposing federal legislation backed by credit card companies which made declaring bankruptcy harder for families in debt - precipitating a clash with then-Senator Biden which still rankles Warren today.

"Middle–class Joe" spearheaded the bill. Testifying before his committee, Warren strenuously objected that it punished average Americans for circumstances beyond their control. “You're very good, professor," Biden responded.

Warren was not mollified. In her reading, the bill's enactment captured the interplay between politics, public policy, and corporate influence which slights the interests of ordinary people. But those who dismiss Warren as hostile to business overlook the considerable prescience which pushed her even further into the arena of public policy.

Beginning in the early 2000s, Warren predicted that economic inequalities, predatory lending, burgeoning consumer debt, and the rising cost of housing, healthcare, and education would help precipitate an economic catastrophe. It happened in 2008: the collapse or near-failure of major Wall Street institutions and the ruination of millions of Americans whose mortgages went underwater—which in turn precipitated a bailout of banks deemed "too big to fail."

Asked by Congress to chair a committee overseeing the government's Troubled Assets Relief Program, Warren immersed herself in the toxic aftermath of private irresponsibility and governmental indulgence. This led to a central role in drafting legislation which created the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, which she designed to protect Americans from deceptive marketing and predatory lending.

Prevented from squelching the CFPB, Wall Street and its Republican allies stymied her hope to become its first director. In what must be counted as a cosmic irony, they succeeded in converting Warren into a 62-year-old novice candidate for senator from Massachusetts.

As a candidate, the main line of attack on Warren was that she was engaged in progressive class warfare which included raising taxes on the wealthy. Her response invoked the realities of societal interdependence:

There is nobody in this country who got rich on his own. Nobody. . . . You moved your goods to market on the roads the rest of us paid for; you hired workers the rest of us paid to educate; you are safe in your factory because of police forces and fire forces the rest of us paid for. You didn't have to worry that marauding bands would come and seize everything your factory. . . . Now look, you built a factory and it turned into something terrific. . . . God bless. Keep a big hunk of it. But part of the underlying social contract is, you take a hunk of that and pay forward for the next kid comes along.

What's most telling about this unvarnished view of social comity is that a conventional politician - such as, say Joe Biden - would never think to say it. Her foundational perception informs their differences now.

In Biden's account, Trump is an aberration—as though America got hit by a moon rock. His tacit slogan seems to be "back to the future": all we need to restore the supposedly Halcion days of Obama-Biden is to excise Donald Trump. In contrast, Warren views Trump as a warning that we must change the economic and social dynamics which produced him.

It's no surprise that for many on Wall Street, and among America's wealthy, Warren is anathema. With honorable exceptions—Warren Buffett leaps to mind—the contemporary rich are not notable as social visionaries who grasp that their long-term self-interest may require political and economic conditions which give average people what they consider a reasonably fair shake. Instead the economic elites seem to view Warren with the same myopia with which their generational antecedents saw the two Roosevelts—both of whom wound up rescuing capitalism from its own excesses.

That Warren has foresworn big-dollar fundraising—a crucial wellspring of the distrust average Americans feel for politicians and their donors—deepens this unease among the wealthy. By contrast Joe Biden is outright cuddly, subsumed by the rituals of self–abasement which politicians privately acknowledge shrivel their souls and saps their independence—phone calls and fundraisers spent captive to the solipsism of their funders. Booker, Harris, Gillibrand, Klobuchar—even Mayor Pete—are similarly engaged, thereby assuring wealthy donors that, unlike Warren, they are adequately socialized.

The obvious comparison is to Sanders. But those who conflate Warren with Sanders misconceive her. Until 1996, she was a registered Republican "because I thought those were the people who best supported markets." She decamped upon concluding that the interests who dictated the GOP's economic nostrums were subverting how a truly free market should work. By her own account, she's a "capitalist in her bones" who would liberate the marketplace from the suffocating dominance of quasi-monopolists; break the corrupt nexus between government and special interests; restore a vibrant middle-class; and broaden economic opportunity.

In short, where Sanders seeks to steer capitalism toward socialism, Warren is bent on saving capitalism for all—and from itself.

One of her two major tributaries prioritizes tackling the problems which beset her family, and overwhelm many ordinary Americans today—including the increasingly prohibitive costs of healthcare, childcare, housing and education. Her proposals are distinctive, detailed, comprehensive—and, she squarely acknowledges, expensive.

She is least original concerning healthcare: in a rare pander, she wanly endorses single-payer, a progressive litmus test which, once the details are known, polls badly enough to become a purple state poison pill. Clearly aware of this, she acknowledges cheaper alternatives for achieving universal coverage, including Medicare For All. More distinctively, she proposes that the government manufacture affordable generic drugs where the marketplace fails to provide them.

Far more transformative is her plan to provide universal childcare. For average families, the cost of childcare consumes 10 percent of their income, and frequently more. This is a particularly heavy yoke for low income families and single parents. The quality of care is often poor; those providing it are generally ill-paid. Collectively, these burdens can erode family finances and discourage second earners from entering the workplace or working full-time, a vicious cycle which also damages the economy at large.

To ameliorate this, Warren proposes a network of childcare facilities, supervised and paid for by the federal government, which charge families based on a sliding scale which reflects their income. Her plan would "create a network of childcare options that would be available to every family." Families earning less than twice the federal poverty line would pay nothing, while higher income families would contribute a commensurate fee, lowering the overall cost of the program.

Further, Warren would establish national quality standards for child care facilities and raise workers' wages to approximate those of local public school teachers. By reinventing American childcare, Warren means to better the lives of parents and kids alike.

Some critics are reflexively repelled by the idea of federally-supervised childcare, regardless of its quality or who benefits. Others note that her proposal skips nuclear families struggling to keep one parent home—whether to care for an infant or very young child, or simply because this is the familial model they prefer. A less expensive childcare option would be expanding the Child Tax Credit. And increasing the Earned Income Tax Credit would help stay at home parents.

But neither option would provide the universal quality childcare that Warren envisions. Here, as elsewhere, she challenges her rivals to do so—or say why not.

The same is true for our middle- and lower-class housing crisis. Affordable housing is a grave concern for millions of Americans—many of whom find homeownership beyond their reach. But it's of special moment to African-Americans.

Among the instruments of America’s systemic discrimination were redlining, the denial of mortgage financing, predatory lending, and racially motivated zoning—all countenanced or actively encouraged by the federal government during the New Deal and beyond. This prevented blacks, then and now, from building wealth the way so many whites do: homeownership. Warren makes this point explicitly.

Further, the embedded concentration of low-income housing isolates struggling families by race and class, limiting mobility and access to quality education. And the 2008 financial crisis, as Warren well appreciates, saddled homeowners with mortgages far greater than the worth of their home, generating bankruptcies or foreclosures.

Housing security is essential to millions of families, and homeownership is integral to the American dream. Both of these ideals are dear to conservatives as well as liberals. Yet only Warren offers comprehensive proposals to address them: Leveraging federal funding to build over 3 million new housing units for low- and middle-income families while lowering rents by 10 percent. Assisting those hurt by federal housing policies through helping communities historically denied fair mortgages. And providing financial support for those whose housing equity was destroyed by the financial crisis.

She would fund all of this by raising estate tax thresholds to their levels at the end of 2008 and then raising rates above those thresholds—which, Moody's Analytics estimates, would totally offset the cost. The bargain she proposes is essentially this: raising the estate tax on an estimated 14,000 families in order to extend homeownership and decent housing to many millions of Americans.

Most controversial is Warren's plan to provide free college and student debt relief for America's young people. There is a direct correlation between educational attainment and adult earning power; the ballooning expense of higher education limits the ability of the young to realize their potential and thereby enrich our society. Some qualified students don't attend college, others drop out, still others graduate burdened with debt.

All of which contributes to a class system based on birth, not merit, and an increasing lack of social mobility between the top 10 percent of Americans and everyone else. In response, Warren would eliminate tuition and fees at every public college in America; offset expenses like books, room, and board by extending Pell Grants for lower-income families; and allow historically black private colleges to opt into her tuition-free model.

There are important criticisms of Warren’s model. For instance, should we be paying for free college for the affluent? Others worry that a federal windfall would further balloon tuition and fees, burdening taxpayers in turn. Or, perhaps, that this plan would relieve colleges of the obligation to address the root causes of inflated tuitions, while encouraging students to study the wrong things at leisure in pursuit of degrees which confer little benefit.

All fair points. The unique obligation of Warren's rivals is to specify how, or whether, they would attack this problem; to whom they would provide benefits; and how they would control costs. Warren's plan may be over-inclusive and thus gratuitously expensive. But credit her with yet another specific proposal to create individual opportunity while buttressing America's workforce.

Her student-debt relief plan is less fiscally problematic. She argues that burgeoning tuition has generated potentially stifling debt. Moreover, she notes, "Students of color are more likely to have to borrow money go to college, they borrow more money when they're in college, and they have a harder time paying for it when they get out of college"—all while having fewer family assets to draw on.

To offset these effects, she proposes to cancel up to $50,000 in loan debt for an estimated 42 million Americans with a household income under $100,000. For those making more, she would establish a series of income tiers which provide diminishing relief, providing none for households earning more than $250,000.

This plan, she contends, would erase debt altogether for 75 percent of beneficiaries; would substantially increase wealth for minority families; and would provide a middle-class stimulus that would boost economic growth, increase home ownership, and fund small business formation.

Here the objections are less persuasive. One expert insists that forgiving just $10,000 in loan would eliminate debt for a third of borrowers, and that we needn’t spend so much money on diminishing returns. Others argue that Warren’s plan is regressive, providing the most relief to people who pursued the most expensive educations. Another is that taxpayers who did not attend college would help fund relief for those who did—a critique that applies to a myriad of existing federal programs.

Overall, the most compelling is who would pay for Warren’s sweeping proposals—and how.

Again, Warren is unflinchingly specific: Her principal engines are a 7 percent tax on corporate profits over $100 million and a 2 percent tax on wealth over $50 million, rising to 3 percent above $1 billion.

Warren is unrepentant about complaints that this amounts to an un-American bleeding of the rich. "Here's the stunning part," she says. "If we put that 2 percent wealth tax [per dollar] in place on the 75,000 largest fortunes in this country . . . we can do universal childcare for every baby, 0 to 5, universal pre-K, universal college, and knock back the student loan burden for 95 percent of our students—and still have nearly $1 trillion left over."

Among voters, support for her wealth tax polls around 60 percent. Little wonder: As Warren Buffett notes, the only successful class war in America is being conducted by the wealthy, and the wealthy are winning—as evidenced by Trump's budget-busting corporate tax cut.

The most telling criticism of Warren’s plan is that wealthy Americans will simply duck the new taxes by shipping liquid assets overseas. While this is not the most attractive argument—some unreasonably resentful souls view tax avoidance by billionaires as more venal than patriotic—it is inarguably real. Shortfalls in collectability have caused most European countries to abandon a wealth tax. Nonetheless, Warren argues, her proposal contemplates tax avoidance at 15 percent, and enhances enforceability by strengthening the IRS and imposing heavy fines on those who undervalue assets, hide wealth abroad, or renounce their U.S. citizenship.

As always, the salient question is what alternatives—if any—the other candidates propose and, if put to the choice, what measures the tax-averse wealthy would dislike least. Options include a substantial raise in marginal rates, hiking the estate tax, treating capital gains as ordinary income, repealing all of Trump's tax cuts, eliminating the carried-interest loophole, and closing individual and corporate tax shelters.

All of these options may eventually become exigent: The need for revenue flows not just from spending proposals like Warren's, but from the crippling deficits arising from decades of tax cuts which, whatever their proponents claimed, have never paid for themselves. Once more, Warren issues a critical challenge to other candidates: How would you fund government, and what is your concept of fiscal responsibility and equitable taxation?

This much is certain: If she were to be thwarted on one revenue measure, a President Warren would advance others. Her vision for America is that true capitalism must serve the many, and opportunity should be lived every day in the homes and workplaces of ordinary Americans.

But this vision includes much more than taxing and spending. The second aspect of Warren's program may be the most interesting: her comprehensive plan for pre-tax reforms which would seek to fortify American democracy by transforming corporate behavior while costing taxpayers virtually nothing.

Specifically, Warren would try to use government to ground corporate decision making in a far-sighted ethic which transcends the accretion of shareholder value and political power. While this rebalancing of interests may sound revolutionary, it’s not. American businesses adhered to it in living memory..

Warren evokes the prevailing corporate credo which existed between World War II and the late 1970s—a communal compact which included fair wages, a secure retirement, proportionate executive compensation, equitable taxation, hard bargaining between businesses and unions, and curbs on corporate power and size. The economic results from this compact—rising opportunity and diminishing income inequality—used to be viewed as the essence of America.

But beginning in the 1970s, this version of capitalist America slowly vanished. Faced with global competition, corporate executives prioritized deregulation, reducing taxes, resisting unionization, depressing wages, cutting benefits, and overpaying themselves for maximizing shareholder values by firing workers at the cost of shared prosperity. Ayn Rand's unfettered corporate superman, as repackaged by Milton Friedman, symbolized the superior wisdom of "free markets" liberated from larger social concerns to grow the GDP—while appropriating its largesse to a diminishing percentage of Americans.

The potentially destabilizing social dynamics have become obvious. True, unemployment is low and yes, the stock market thriving. But beneath this lurks the political iceberg of yawning gaps in wealth and income not seen since the 1920s.

America's top 10 percent averages more than nine times the income of the bottom 90 percent. For the top 1 percent it’s over 39 times as much—and this has doubled since 1968. When you get to the top 0.1 percent, they possess more wealth than the bottom 80 percent, while the top 1 percent controls twice the wealth of the remaining 99 percent—another gap which has widened dramatically in the last 40 years. This does not bode well for our sense of common citizenship and shared opportunity—or for the long -term health of our political system.

This change was accelerated by another: that corporations have become “people” with the right to spend unlimited money to influence public policy. Far from promoting democracy, too often mega-corporations and the wealthy use government to protect them from the consequences of democracy. As Louis Brandeis argued, “We may have democracy, or we may have wealth concentrated in the hands of a few, but we can’t have both.”

It’s little wonder, then, that more average citizens—and especially millennials—are now asking whether "democracy" or "free enterprise" as currently practiced are inimical to their interests. This is what accounts for the rising interest in socialism (albeit multiply-defined) among young people. As best she can, Warren means to restore the capitalism which gave baby boomers lives that their millennial children despair of replicating.

One of Warren’s goals is to redefine corporate responsibility to the society which enables businesses and their shareholders to profit. Warren means to broaden corporate decision-making, curb corporate political activities, and re-incentivize CEOs to balance the interests of shareholders with that of customers, employees, and the community they inhabit.

Specifically, her plan requires that large corporations obtain a charter of corporate citizenship which codifies their greater obligations to society; that employees select 40 percent of board members; that 75 percent of shareholders and directors approve corporate political activities; and that executives hold shares they receive as compensation for at least five years, thereby preventing them from cashing in on short-term decisions made for personal gain.

No doubt many shareholders would object. But Warren's proposals cost the taxpayer nothing. Nor do they empower government to make economic decisions—they simply repurpose corporate governance to benefit society writ large.

In this spirit, Warren wants to improve the lot of workers. In recent decades, large corporations began dictating the terms of existence for millions of Americans, particularly non-union workers: depressed wages, vanishing benefits, longer hours, rising insecurity, diminished privacy, strains on family life, and a pervasive sense of political and personal impotence. Warren would safeguard unions, raise the minimum wage, and curb mandatory arbitration and non–compete clauses in employment contracts—restoring some of the dignity and security capitalism once afforded working people.

Our most existential challenge involves climate change. In concept, Warren somewhat tepidly endorses the Green New Deal, perhaps wary of its utopian appendages and vagueness about how to realize its transformational goals. Of more immediate efficacy is her plan to bar further fossil fuel extraction from public lands, thereby reducing by one-quarter all U.S. greenhouse gas emissions, while using them to produce 10 percent of our energy needs from renewable sources—which is a practical and affordable beginning.

Beyond this, she would make environmental accountability another aspect of corporate citizenship by mandating that corporations disclose their greenhouse gas emissions; their ownership of fossil-fuel related assets, and their strategy for ameliorating the physical and regulatory risks posed by climate change. Again, this costs taxpayers nothing—it simply asks corporations to publicly reckon with their environmental impact.

Similarly, Warren addresses the ethical quagmire in which corporations spend billions to rewrite public policy by compromising its authors—exemplified by polluters who, behind closed doors, influence the EPA to minimize curbs on pollution. Inevitably, this unseemly process generates undue influence, outright corruption—or, in Trump's case, a blatant commingling of governance with private financial interests evinced by his pursuit of projects in Russia.

Warren would buttress public integrity by barring selected public officials from owning individual stocks or later pursuing lobbying careers; requiring the president and vice president to place assets which raise potential conflicts of interest into a blind trust; compelling them to release their tax returns; barring direct political donations from lobbyists to legislators; forcing lobbyists to disclose the interests they represent and their meetings with public officials; and creating an independent agency to investigate ethics violations. Beyond the concern that this regime keeps expertise from moving between government and business, one struggles to imagine a principled objection to Warren's reforms.

Similarly, millions of Americans have already paid for the de facto immunity granted white-collar criminals and predatory financial institutions. Warren would discourage such predation by prosecuting financial malefactors, establishing a unit dedicated to investigating crimes at large financial institutions and requiring senior executives at banks with over $10 billion in assets to annually certify that they have "found no criminal conduct or civil fraud."

Holding the citizens of Wall Street to the standards of honesty which govern everyone else is, if one thinks about it, the very opposite of class warfare.

So is the revival of antitrust enforcement. At the behest of large corporations and Friedmanesque ideologues, government stopped enforcing the laws which prevented private enterprises from becoming so large that they slipped beyond control—stifling competition, limiting innovation, retarding new businesses, and using their leverage to gain economic dominance and political immunity.

Notably, Warren's own party abetted this burgeoning consolidation. From 2005 to 2015, the number of independent retailers fell by 85,000; small manufacturers by 35,000. Since 1980, the number of new firms launched every year has fallen by two-thirds. A survey of small business owners in 2016 found that 61 percent said that the federal government "should more vigorously enforce antitrust laws."

Despite Republican claims to champion their cause, protecting small businesses informs Warren's plan to resuscitate antitrust enforcement and crack down on what she perceives as monopolies. "Promoting competition used to be a central goal of economic policymaking," she writes. "Today, in market after market, competition is dying as a handful of giant companies gain more and more market share."

Here Warren stresses the power of tech companies like Amazon, Google and Facebook to kill or acquire competitors. Overall, the New Yorker reports, Amazon, Apple, Google, Facebook and Microsoft "have hoovered up 436 companies during the past ten years, almost all without antitrust reviews. Facebook even deployed an app that looked for rivals that it could either buy or kill."

Beyond this, Amazon uses its platforms to sell its products while dictating the rules for its competitors. In one notorious incident, it leveraged its negotiations with a major book publisher over book prices by restricting customer access to its books.

Inevitably, political puissance follows. Last year, Google, Facebook, and Amazon spent $48 million in lobbying, purchasing the sway through which they—Facebook in particular—have forestalled regulation.

As Warren sees it, "today's big tech companies have too much power . . . over our economy, society, and our democracy. They've bulldozed competition, used our private information for profit, and tilted the playing field against everyone else. In the process, they have hurt small businesses and stifled innovation. . . . [They] act, in the words of Mark Zuckerberg, 'more like a government than a traditional company.'"

In response, she calls for a revival of the trust busting traditions Theodore Roosevelt invoked during the Gilded Age. She would break up Google, Amazon, and Facebook; forbid them from owning any participant on their respective platforms; unwind mergers like Facebook's acquisition of Instagram and What's App, and Amazon's purchase of Whole Foods and Zappos; bar tech companies from sharing or transferring user data with third parties; and reverse "illegal and anti-competitive tech mergers" in order" to help America's content creators . . . keep more of the value their content generates."

Ironically, Warren announced this plan on Facebook—after all, it reaches roughly 68 percent of Americans. In a self-revelatory coda, Facebook removed her ads, stating that they violated corporate policy on the use of Facebook's logo. It restored the ads only after Warren remarked: "I want a social media marketplace that isn't dominated by a single censor."

No doubt Facebook provides a service by linking the willing, even as it peddles their privacy, gives misleading testimony to Congress, serves as a vehicle for undermining democracy, and injects hatred and deception into the American mainstream—most recently by refusing to remove blatantly doctored videos of Nancy Pelosi, presumably because they did not abuse its logo. Similarly, Amazon benefits Americans in their capacity as consumers while underpaying and bullying its workers.

For some experts, these malignancies are outside the reach of antitrust law which, as currently written and interpreted, focuses on companies which lower output or raise prices. Given an increasingly conservative judiciary, to use the antitrust laws as Warren proposes may require additional legislation—a heavy lift, though she proposes to facilitate the passage of her program by eliminating what remains of the filibuster.

For thoughtful Americans across the political spectrum, Warren's candidacy raises a fundamental question: What version of democracy and capitalism do you want? Warren speaks to the inclusive ideal of fairness, opportunity, and a government responsive to all. She posits a future in which we have a genuine democracy and a market which is truly free.

The central question Warren herself asks is: "How do we think government should work and who do we think it should work for?" Her answer is clear. Those to whom her proposals give pause should pause to consider what they propose instead. For by reforming capitalism, Warren could save it from far worse: a downward slide toward oligarchy which invites a Sanders-style counter-revolution.