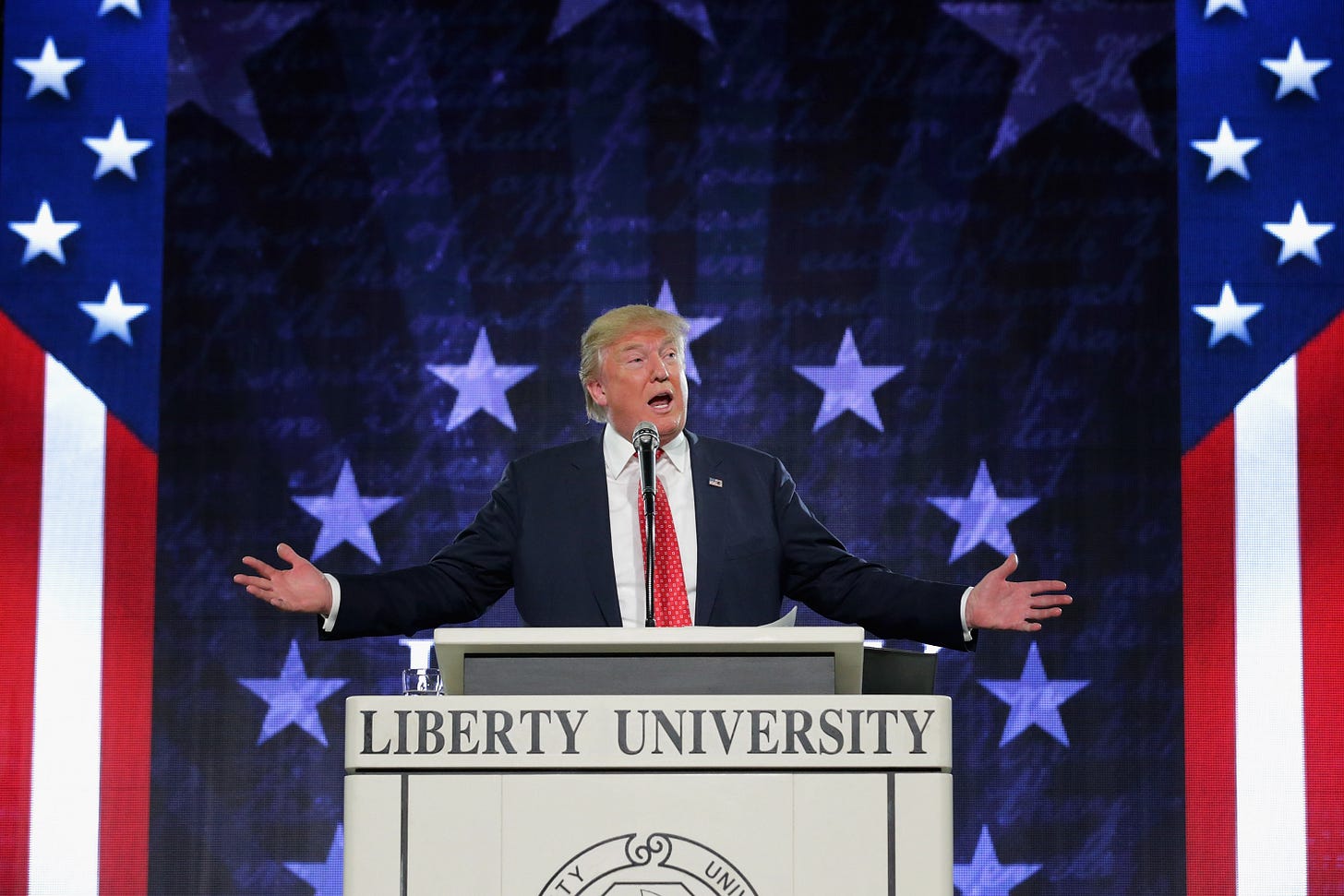

Why Evangelicals Support Trump—and Why They Shouldn’t

Worry about ‘Christianophobia’ is understandable. But Trump is no true ally—and his immorality, race-baiting, and sexism give his Christian supporters a bad name.

[This article is adapted from an essay that appears in The Spiritual Danger of Donald Trump: 30 Evangelical Christians on Justice, Truth, and Moral Integrity, edited by Ronald J. Sider and just released by Cascade Books, an imprint of Wipf and Stock Publishers.]

When Donald Trump came down that escalator in 2015, I had nothing but contempt for the man. I had heard him a couple of times delivering political commentary on Fox News and soon learned to go to CNN or MSNBC as soon as he came on (I watch news across the political spectrum). I had heard of his show The Apprentice, which also did not inspire much respect for him. I figured that he, like many nonpolitician presidential candidates, would be the candidate of the week for the Republicans and then we would get to the more serious candidates.

As his lead persisted in the Republican party through the winter early spring of 2016, I became more worried. I wanted two viable candidates for president. I used my Facebook page to deride Trump and tried to convince some of my conservative friends not to support him. When he won the nomination, it was disheartening to think that one of the major political parties would have such an incompetent candidate. I assumed he would lose but discouraged my Christian friends from voting for him. I even placed articles in The Stream, a conservative Christian online magazine largely favorable to Trump, to discourage Christian support. I knew my effort would have little influence, but I wanted to be able to tell my kids years later that I did my part in stopping Trump from becoming president.

On election night I settled in to watch Hillary Clinton become president. That prospect did not make me happy, as her many flaws were quite apparent. But at least she was not Trump and overall, I felt the country was better off having her as president. As I watched the returns at around 8 p.m. it began to dawn on me that Trump could become president. Ashen faced, I told that to my wife, who stared at me in disbelief. Until that moment, I did not think he could win. About an hour later the possibility became reality and I knew that Donald Trump would be the next president of the United States.

I had hopes that perhaps Trump was elected president without outsized support from Christians. That hope was dashed when I learned that a higher percentage of white evangelicals supported Trump than supported previous Republican presidential candidates. I expected more white evangelicals to vote for Trump than Clinton as they are Republicans. But for evangelicals to support Trump more than other Republican presidential candidates blew my mind. I did not know what just happened. I still wonder how a crude, incompetent, race-baiting sexist could win the presidency of our country.

Ultimately what I think happened was that Trump had spoken to needs among evangelicals that were not being addressed by other political candidates. One of the most important issues can be seen in my research on Christianophobia—the unreasonable hatred or fear of Christians. Many evangelical Christians see Trump as someone who will save them from Christianophobia. And while I understand and respect the nature of these Christians’ fears—in fact, I share them—I believe that Trump is not only not a solution to these issues but in the long run he will make things worse.

Is Christianophobia a Problem?

When the topic of Christianophobia comes up there are those who argue that it is merely Christians who have lost their privilege. Yet is it a privilege to be able to obtain a job in academia free of religious bias?

Is it a privilege to have religious leaders in student organizations who believe in their religion? The development of all-comers policies and the way they have been used to target Christian groups has revealed this threat to freedom of association.

Outside of academia there are episodes of a lay-pastor being fired from his position as a district health director due to his sermon and a fire chief being fired due to a Christian book he wrote.

It is more reasonable to see these events as rights, rather than privileges, being denied to certain Christians.

My own research shows that those with anti-Christian hatred tend to be white, wealthy, educated, and male.

They also tend to be politically progressive and irreligious. I suspect that they are quite powerful in cultural centers of our society such as academia, media, and entertainment. Many Christians, especially conservative Christians, see evidence of Christianophobia in their lives yet see no attempt in our cultural institutions to document it. It is the frustration that comes from this disconnect from their experiences—and the way it is not portrayed in the larger culture—that led some to Trump. Indeed, when I talked to many of my friends who voted for Trump, one common phrase I heard was, “Well, he may be bad but at least he does not hate me and will leave me alone. Clinton hates me and will not leave me alone.”

I want to say to my Christian friends, especially the evangelical ones who most support Trump: I hear you. Christianophobia is real. I have studied it and debated with those who do not believe it exists. Trump has promised to protect Christians. The seeking of political control is one way to try to deal with Christianophobia. But it is the wrong way.

The Problem Is the Culture

We may not know exactly what has led to the rise of anti-Christian attitudes, but we do know the arguments used to support it. Many of those with such attitudes envision Christians as bigoted, intolerant, racist, unthinking, and crude. These are also qualities that are tied, with good reason, to President Trump. To have Christians seen as supportive of Trump is to reinforce some of the Christianophobic stereotypes. Support of Trump will ironically reinforce many of the cultural stereotypes working against Christians in the long run. I do not doubt that in the short term there are protections gained by Trump. But that is shortsighted. In the long term any legal protection gained because of Trump will be overturned by a culture that is more anti-Christian because of current evangelical support of Trump.

Let me deal with a couple of replies that I have encountered when presenting this argument. One argument is that we should look at what President Trump is doing to the courts. If there is one area where he has shown some degree of competence, it is his naming of judges and the ability of Senator Majority Leader Mitch McConnell to get them appointed. It is presumed that these judges, when facing cases that touch on political issues that conservative Christians care about, will rule in a way that conservative Christians would like. That presumption may be wrong, but let’s stipulate that President Trump has been good for those issues in the short term—and that since federal judges are appointed for a lifetime, the effect might last in the long term, too.

But even lifetime appointments come to an end. If our culture changes so much to widely accept Christianophobia then those cultural sentiments will outlast those judges. Eventually they will be replaced by judges who are more in line with those hostile sentiments. All the achievements can be overturned just like the state political victories against same-sex marriage. With a culture deeply ingrained with Christianophobia, it is uncertain if the changes brought about by judges and justices with less sympathy to Christians will ever be remedied if religious bigotry is accepted. Trump’s judges and justices may protect today’s Christians. But our children and grandchildren will have to suffer the brunt of the hostility the support of Trump has generated. Working on cultural change is the proper long-term play.

The second major pushback I receive is that those who hate Christians will continue to hate us regardless of whether we support Trump or not. True. Some people have such hatred in their hearts that nothing we do short of capitulating to all their political and social causes will satisfy them.

But thankfully, they do not make up most of the country. A lot of folks do not hate or love Christians. They live their lives not thinking much about Christians. But when they see Christians massively supporting a race-baiting, bombastic, sexist, and sexually immoral president, they can naturally begin to think of Christians as hypocrites. They can also become more open to Christianophobic arguments when frustrated by having a president with those qualities and blame Christians for putting him into office. Whether we support Trump or not will not matter to those who already have high levels of anti-Christian animosity, but it can raise that animosity in those who previously had a neutral attitude towards Christians but are turned off by the vices of Trump. It is a mistake to think everyone’s mind is made up about what they think of evangelicals. There are many people who will still be influenced by the support evangelicals have given to Trump.

Political Leaders and Scripture

To deal with Christianophobia, we must challenge the cultural values emerging from this type of intolerance. But in a very practical manner, evangelical support of Trump is making our culture even more toxic for Christians. For utilitarian reasons alone, Christians should not throw their support behind our current president.

But my argument is not limited to utilitarian concerns. The way Christians have come to support Trump does not fit with a proper understanding of the Scriptures. I acknowledge that I am not a trained theologian and so people may rightly argue with my interpretations. But I am confident that the evidence for Christians to be cautious about putting too much faith in their political issues is very strong.

Any fair assessment of the Old Testament and the trials of the children of Israel consistently comes back to the theme of relying on political figures instead of God. From the very beginning of the formation of Israel, Jews were warned about seeking a king to be the solution to their problems.

And what were the problems that the Jews needed to address? They were a nation in the middle of other nations that did not like them. The idea was that a king could fight for them and they were jealous of the kings in other nations. And the problem of looking to political leaders was not limited to recruiting Saul as their first king. The children of Israel not only sought to rely on other Jews for the projection and leadership they wanted. They also looked to powerful foreign nations for protection.

In other words, they believed more in the protection they could obtain from individuals who did not accept their God-given values than a God who has said he would protect them. Sound familiar?

I am not arguing that Christians should not get involved in politics. Christians should feel the freedom to engage in politics just as much as anyone else. And there is nothing sinful about advocating for issues of life, religious freedom, and justice—quite to the contrary. But when we become so loyal to a political party that we are afraid to correct the leaders of the party, then we are not merely participating in politics. We are looking to politics to save us.

This explains not only the hesitation of many Christians to condemn some of the ugliness that comes from President Trump’s mouth, his constant tweets, and administration, but also their surprising willingness to change their attitudes about moral values. After the 2016 election, surveys showed that conservative Christians went from being the people who were most supportive of requiring moral political leaders to being those who least required such morality. Efforts by Christians to placate President Trump suggest an undeserved level of loyalty.

I cannot help but think that this type of placating and loyalty is due to a sense of desperation among conservative Christians. In a society where they feel the effects of Christianophobia, they want to turn to a powerful political leader for protection. That sentiment is humanly understandable, but it is not in keeping with biblical commands to not live in fear and to not prioritize human resources over God’s resources. If we claim to have a power beyond what those outside of our faith enjoy, then we have to live it out. Looking for political muscle just like any other special interest group is the opposite of living out that faith.

Trump and the Split among Christians

Beyond connecting Christians to some of the more unsavory parts of Trump, the danger of Trump is also the danger of division within the Christian church. Trump is especially unpopular among young people and people of color. There is evidence that even among evangelicals, younger persons are less likely to support Trump. At a time where it has become more important for Christians to hang together and deal with anti-Christian attitudes, President Trump has created even more division. To be sure, the division is our fault more than it is Trump’s fault. The way some Christians have placed Trump on a pedestal has created a divisive situation considering the way he freely dehumanizes others.

It would not be fair to place the entire responsibility upon those defending Trump. But it should not surprise us that a political leader who traffics in divisive rhetoric would have followers who spread division. I have heard again and again that some Christians not only fail to critique the dehumanizing comments of Trump, but they also like him because of that “tough man” approach. They often say that there is a need to go to “war” against progressives and that Trump’s hostility towards those progressives is a welcome change over other, more civil political leaders.

Let us admit that there are progressives who will mistreat Christians the first chance they get. Even in that situation, Trump’s attitude is the opposite of how we, as Christians, are called to approach those progressives. We are not to treat them with the same type of dehumanization that we perceive them willing to direct against us. That does not mean we have to be a doormat, but there is a big difference between standing up for our own rights and seeking to destroy our political opponents by maligning them.

I fear that many of Trump’s evangelical supporters have brought this “we are in a war” perspective into their interactions with other Christians. They are impatient with those of us who are not willing to sign up for this battle. We are seen as traitors. I have been accused of acting out of fear due to my opposition to Trump. Unfortunately, I have seen a good deal more fear on the part of those who support Trump. They are reacting out of fear because of what may happen if progressives take over our government. They fear a loss of their rights and the passage of laws of which they disapprove. Trump is seen as the solution to their fears. And out of those fears, they often lash out at those of us who will not support him. As such, while there is no doubt that at times Christians who oppose Trump have acted in ways that have made these divisions worse, many evangelical Trump supporters feel pressure to force those who will not support him to join in their pro-Trump agenda.

Only when we can detach ourselves from this unholy alliance with our contentious president will we be able to turn down the temperature in this heated conflict and concentrate on building the Christian community we will need in a post-Christian world.

What to Do?

To some degree the damage has already been done. No matter what happens in 2020, the image of Christians putting Trump into power in 2016 will remain. However, it may be possible to limit the damage if we refuse to continue supporting him. Perhaps rejecting Trump now will resonate with some individuals. In the Doug Jones/Roy Moore Alabama Senate race in 2017, there was a fear that Christians would overlook the problems connected to Moore and send him to the Senate. Instead they stayed home. They could not support Jones, but neither were they willing to back Moore. That removed the potential of Moore being yet another cultural noose around our neck. Perhaps with a noticeable drop of evangelical support and a Trump loss, we can lose some of the cultural baggage of the linking of Christians to Trump. But we should not be naïve about that possibility either. The damage may have already been done.

But perhaps even more troubling than the vote for Trump is the unwillingness of Christians to challenge him. It is one thing to argue that we must vote for Trump because of the alternative. There is a rational argument of selecting the lesser evil. But there is no rational argument for once having selected that evil, to go on to allow that evil to go unchecked. We have already seen that Christians have altered their stance on the morality of leaders to suit Trump. Perhaps most notably is the public statement of Tony Perkins about giving Trump a sexual “mulligan.” How much will we be willing to sully our reputation to protect Trump?

But it is not only his moral failings that Christians are too eager to defend. Too often I have encountered Christians who twist themselves in all sorts of knots in their efforts to defend Trump on his race-baiting. I had one encounter with a leading Christian supporter of Trump who insisted that Trump does not engage in race-baiting. When I pointed out that Trump had clearly lied about not knowing “anything about” David Duke and that he did this to pacify white nationalists, his response was that all politicians lie. I could not believe what he had just argued. Do politicians lie to make racists feel better? The denial of this person to see any problems with many of Trump’s race-baiting statements indicates a desire to defend Trump no matter what he says or does. This must stop.

If Christians do not push back on the disturbing attributes of Trump, then we will own those attributes. For example, if enough Christians accept the perceptions of the leader in the previous paragraph, then our faith will become known for not caring about the race-baiting statements of our president. This will translate into Christians not caring about racism and people of color. The argument that we must vote for Trump as the less-bad option will not save us from being labeled racist if we do not challenge Trump’s race-baiting.

Or let me put it this way. Many conservative Christians accuse Democratic Christians of endorsing abortion because they vote for pro-choice candidates. If those Christians stay silent on that issue, then they have a point. But if Democratic Christians vote for Democrats despite abortion and make it plain that they opposed that plank of their political party, then they do not own the pro-choice label. It is fairer to say that their vote is due to the reality that neither political party accurately reflects their overall political beliefs and they had to make the best of a bad situation. Likewise, if you cannot find it in yourself to not vote for Trump—although I really hope that you won’t vote for him—I would urge you to hold him accountable by becoming vocal about his dehumanizing, race-baiting, and sexism. Too many evangelicals have supported Trump without condemning his vile speech and actions. That failure tars our faith with his actions. We dare not allow him to continue to poison the good name of Christians.