Why You Should Buy an OLED on Black Friday

A $1,000 home-theater setup will give your local multiplex a run for its money, technically speaking.

The crucial technology that could enhance the cinema experience is a COVID vaccine. Someday (soon, please!) life will return to normal and we won’t have to watch every bit of entertainment on our home theater systems. Once that happens, is there any reason to watch movies in a commercial theater?

There’s a lot to consider when choosing a theater over home, including the seats, the ability to pause for a bathroom break, snacks that do not require a separate line of credit to consume, fellow patrons (and their unimpeachable behavior), the shared experience, and finally the sound and picture.

Most of these issues are easy for consumers to discern for themselves. Nobody needs me to tell them the technical reasons to prefer Cheetos popcorn over their home-popped popcorn (since Cheetos popcorn is self-evidently amazing). But information comparing the image quality of a movie theater to a home system isn’t readily available, and it can be very difficult to compare specifications between these two situations. So let me help with that. In passing I’ll also mention sound quality, but judging sound quality always descends into the madness of the audiophiles, who (as everyone knows) are best avoided.

For comparison, let’s consider three situations: a relatively inexpensive home theater system, a fairly high-end home theater, and a standard movie theater. I’m leaving out premium large-format theaters like IMAX and Dolby theaters, which have much more complicated specifications and aren’t as widely available across the country. Let me just stipulate that these and other high-end brands specifically work to have higher technical quality in their auditoriums.

But it’s fair to talk about standard theaters because there’s a written standard for digital movie projection, called DCI (which stands for “Digital Cinema Initiatives, LLC,” the company that holds and maintains the standards). These “DCI-compliant” theaters represent all the theaters that aren’t premium format theaters. Every theater is designed to meet these specifications, so (when everything is working properly and the dust and grease are cleaned out) you should expect a reasonably standard movie experience regardless of which movie theater you go to. This is obviously not completely true, and there are quality control differences from theater to theater, but we’ll talk about the average experience in a standard theater.

For our “relatively” inexpensive home theater, let’s go shopping with just a kilobuck. Something like a $650 LCD 55-inch UHD TV and a $300 sound bar with subwoofer. You can have a pretty nice setup with a streaming system built in and have some dollars left over to buy a standard Blu-Ray player because we like physical media. (Notice that we do not use the speakers built into any television because we have self-respect.)

Then there’s the high-end home theater setup, where we will spend less than five thousand dollars. This system has a $2000 65-inch UHD OLED television, a $750 7.2 channel object-sound compatible receiver, a $170 UHD Blu-Ray Player, and all the rest on really nice speakers for immersive sound.

The first image-related item to address is how eye-filling the screen is. For the movie theater, this would depend on where you sit, but typically it’s recommended to sit about 1 to 2 “screen-heights” from the screen, which is usually midway back in the house. For the both home theater setups, this means sitting 3 to 6 feet from the screen. For a good cinema experience, sitting closer would be recommended, but nobody does that. Most people sit about 8 feet from their screen regardless of the size of the screen, so in almost every home setup the screen is not very eye-filling. Notice that for very wide aspect ratio movies with letterboxing, you’d need to sit even closer because “screen-height” is the height of the image on the screen, not the height of the TV.

Next let’s look at resolution. Both the home theaters have 4k resolution. The movie theater might be 4k, as almost all new projectors installed in the past few years are, but the standard only calls for 2k resolution. And here’s the secret: almost no cinema content is distributed in 4k, and very little of it is even produced at any level in 4k resolution. The streaming services are driving 4k content creation, so more content has a 4k workflow from camera through edit to distribution, but the final content sent to theaters is almost always 2k even if the master was 4k and the projector is capable of 4k projection. That said, a 4k projector will still produce a much nicer picture on screen than a 2k projector for 2k content because it will reduce the “screen door” effect caused by large blocky pixels on the screen.

In real-world audience testing, a large fraction of the viewing audience can’t tell the difference between 2k content and 4k content when properly projected and when the audience is sitting at typical viewing locations. So the extra cost associated with 4k distribution has been avoided without anyone really noticing. Also, I should point out that the DCI standard for content distribution in movie theaters does not support 4k resolution for 3D movies, so all 3D movies are 2k.

For color reproduction, the technical term used is “color space” of the display and content. Since high definition television came along, the standard range of colors for HDTV and Blu-ray discs has been something called “Rec. 709.” It’s a good color space that reproduces lots of color. Digital movie theaters use a wider color standard called “P3,” which can create deeper blues, reds, and greens. P3 covers all the colors that can be seen in the real world by reflected light off pigments, but cannot reproduce “unusually” created colors like the iridescent colors of a peacock feather or a red neon sign. The $5k home theater system can cover almost all of P3, so to any normal viewer it will present the same colors as a movie theater.

But where things get interesting is in the image contrast. One of the things that really makes an image “pop” on screen is how different the bright areas are from the dark areas. This is very hard to do in a movie theater. The projector itself can’t make the screen completely black--some light always leaks through the guts of the digital projection optics. Also, dust on the lens or port window will cause light to scatter from bright areas of the scene and fog the dark areas, making the colors there look muddy and indistinct. Finally, a bright image on part of the screen will light up the whole auditorium, reflect off the chairs, walls, ceiling, and people in the auditorium, and put light back onto the dark areas of the screen and make the image a bit dull. (Tests of the impact of audience clothing on the image quality have been performed and the results showed that what people wear to the theater has a greater impact on the image contrast than the architecture of the auditorium. It was suggested that patrons should be given black viewing robes to improve cinema contrast. I hope they were joking.)

Flat-panel televisions don’t have the same kinds of image contrast issues, but they do have different ones. The $1k system uses an LCD television, and all LCD based sets have problems producing good images in dark regions and rely on a series of backlight tricks to try to overcome this deficiency. The result is usually … not great. The OLED television in the $5k setup is, however, fantastic in this regard. It is demonstrably superior in every way to the contrast of a movie theater, and by a large margin. The colors and detail in dark regions of the image look deep and pure even when very bright highlights exist on the other side of the same image.

The new technology of the last few years has been high-dynamic-range imaging (HDR). This comes in several flavors, and the image will have greatly enhanced highlights without sacrificing the dark regions. The glints of sunlight off of water or the sharp brightness of fireworks in a dark sky are strikingly rendered. (A Dolby senior engineer once used the example of glints from sweat beads on my bald head as a great use of HDR. I remain unamused by this example.) Standard theaters do not support HDR, and the currently installed projectors simply cannot create that level of dynamic range. On the other hand, both the $1k and the $5k system support HDR on paper, but the difference in quality between the two systems will be striking. The OLED system will deliver HDR in a way that is much more vibrant, but both televisions will outperform a movie theater in terms of dynamic range.

In passing, I should mention 3D. Most standard cinemas are 3D capable using circular polarized glasses, and the 3D standard is written into the DCI specification (although it is not required). Neither of our example home theater systems is capable of 3D viewing, and no television manufacturer has made a 3D capable set for several years now. There is a standard for 3D viewing in home theaters, but it’s only supported by standard Blu-Ray discs (not UHD). 3D Blu-Ray discs of new movies are still produced, but very seldom. Very serious home-theater nerds still set up 3D at home with shutter glasses or passive circularly polarized glasses and projectors. But for practical purposes, 3D isn’t really an option at home.

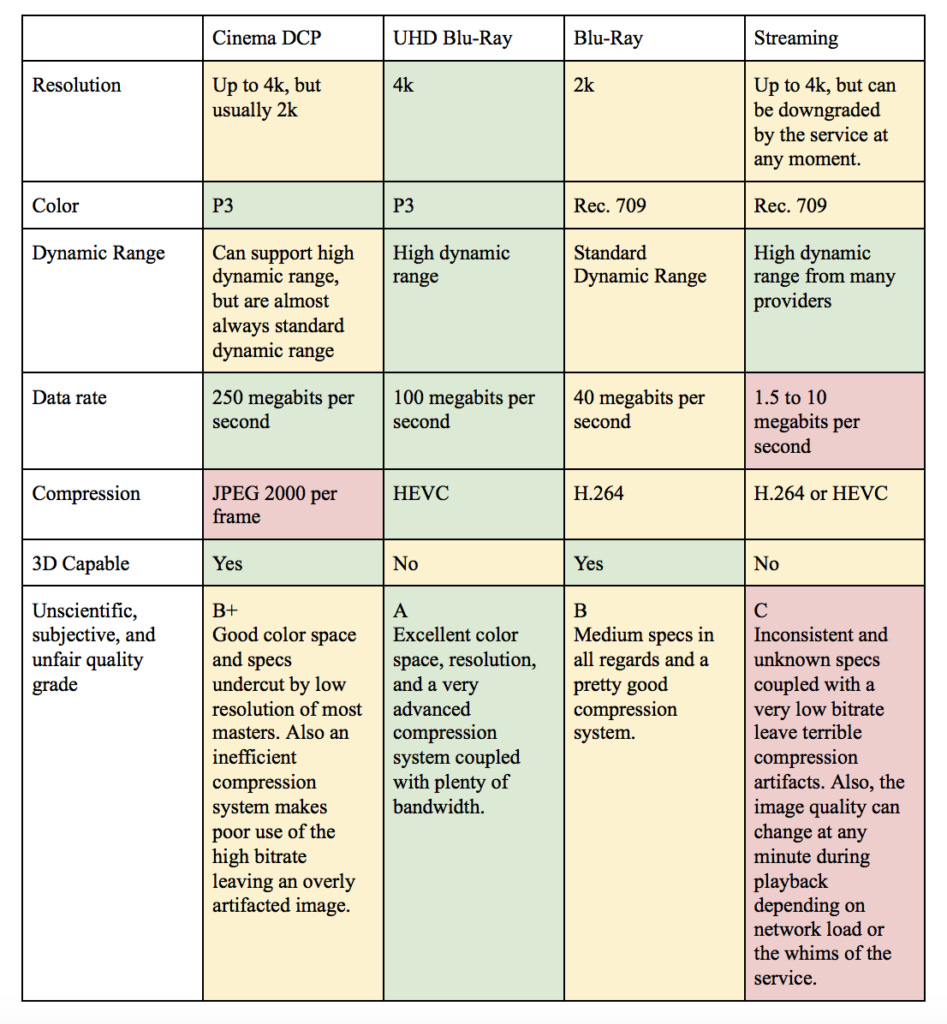

The hardware for watching a movie is one part of the puzzle, but the way we actually receive the movie data is another. For the movie theater, the movie is transmitted as something called a “DCP,” or Digital Cinema Package. In our home setups this is either a Blu-ray, a UHD Blu-ray (a/k/a, a 4K disc), or a streaming service.

In movie theaters, movies are usually shipped in on hard drives containing DCPs. Each frame of the movie is stored as a separate JPEG 2000 file. It’s a high-quality format, but is getting a bit old compared with the technologies deployed at home. While DCPs support 4k, HDR, and high frame rates, almost all movies are distributed as 2k, 24 frames-per-second, and in standard dynamic range. DCPs have a maximum data rate of 250 megabits per second, which is quite a lot, but because the compression system is relatively inefficient, the final image on-screen still suffers from compression artifacts.

Blu-ray discs use a more modern compression system than DCPs, but are limited to a much lower data rate of about 40 megabits per second. Also, Blu-ray has a narrower color range than movie theater DCPs, and is limited to 2k resolution and standard dynamic range.

UHD Blu-ray is the newer standard for Blu-ray discs, and it uses an even more modern compression system. It also provides a higher bit rate of 100 megabits per second, and the color space is the same as a movie theater (P3). Also, UHD Blu-ray discs support HDR and 4k resolution. Although the bit rate is lower than movie theaters, because they use a more efficient compression system, the image quality of UHD Blu-Ray discs in many situations exceeds the quality of a cinema DCP.

Streaming services have different quality specifications, and many can provide 4k HDR content. The bitrate of all streaming services are quite a bit lower than even standard Blu-ray discs, and they range from 1.5 to 10 megabits per second. This means that streaming content will often show compression and block artifacts that would not exist on physical media. For good quality movie presentation, physical media currently beats streaming by a very large margin.

If we take all of these metrics together, a good case can be made that a $1k home theater system is almost comparable to a standard movie theater, and a $5k home theater system is demonstrably better in every metric except for how eye-filling the screen is (unless you sit a bit closer). For most people, the cost of a multi-thousand dollar home setup won’t be offset by avoiding movie tickets. But I have to own some sort of home theater if I want to watch streaming-only titles, so it’s not usually an option to simply forgo a home theater and only watch movies in the cinema.

When I’ve asked theater chain executives about the danger of people staying home and watching movies on their own home theaters, they have often pooh-poohed the idea by pointing out that people have been wringing their hands about TV killing movies since the 1960s. But I suggest that the current threat to movie theaters is different because the technical quality at home is now objectively superior to movie theaters. It is as if in 1960 you had a 70mm CinemaScope projector in your house instead of watching 35mm movies in the theater.

The main draws to go to movie theaters are non-technical at this point: the community experience, the big-room feel, and of course the timing of new releases in theaters and the delay in release to home theaters. The only technical advantages are the slightly more eye-filling screen and 3D.

I believe that if movie theaters are going to compete in the future, they’re going to have to step up their technical game. There are many innovations right on the edge of deployment in movie theaters, including better resolution, better dynamic range, more brilliant color, and better sound. These technologies exist already, and the price has been coming down. Some of these technologies would be very difficult to implement in a home environment and could make a big differentiation between the home and cinema experience. Premium format companies have been deploying some of these technologies for a while now but they aren’t part of the common cinema experience. Hopefully as the moviegoing public returns to their local theaters next year they could be greeted with dramatically improved image and sound quality that will impress.

In the meantime, there are fantastic home theater options out there. And if you mix Cheetos in with your popcorn, you’ll have the whole shebang.