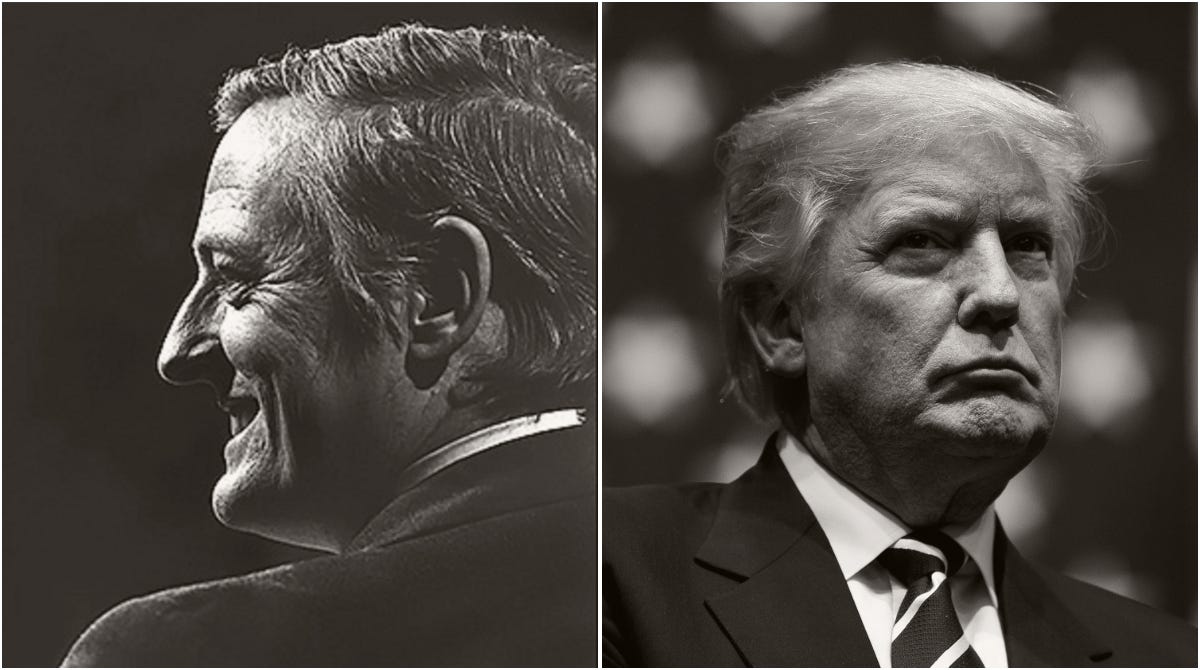

WWBBD: What Would Bill Buckley Do?

There are lessons from William F. Buckley Jr.’s 1965 New York City mayoral campaign for Trump’s 2020 primary challenger.

Last week, former Massachusetts Governor Bill Weld announced the formation of an exploratory committee for a 2020 primary challenge against President Donald Trump. There is evidence to suggest that Maryland Governor Larry Hogan, former Ohio Governor John Kasich, and others are considering challenges, too.

A primary campaign against a sitting president would excite the media, of course. But it could also be a watershed moment in American conservatism. And in many ways, it would resemble another watershed moment in American conservatism: William F. Buckley, Jr.’s 1965 third-party campaign for mayor of New York City.

In announcing his candidacy in National Review on June 24, 1965, Buckley wrote that

Mr. [John] Lindsay’s Republican party is a sort of personal accessory, unbound to the national party’s candidates, unconcerned with the views of the Republican leadership in Congress, indifferent to the historic role of the Republican party as standing in opposition to those trends of our time that are championed by the collectivist elements of the Democratic party.

Trump is no Lindsay, but the parallels to today’s conservative political environment are striking. As such, Buckley’s unusual campaign offers three key lessons for a would-be challenger in 2020.

(1) The high likelihood of defeat is a major asset that can be exploited. When Buckley entered the New York mayoral race, he knew a victory was unlikely. He famously told reporters his first act as mayor would be to “demand a recount,” and joked that he expected to earn just one vote. Following this attitude, he ran a bare-bones campaign, only campaigning part-time and refusing to conduct conventional photo-ops around Manhattan and the outer boroughs. Ultimately, his quips drew media coverage and exposure. And the knowledge that victory was all but impossible allowed him to run a flexible campaign focused on the issues he cared about—and on giving Lindsay headaches.

It is safe to say that even in extraordinary circumstances, the president is an overwhelming favorite to win the Republican nomination. But a challenger could look to Buckley’s example and use those odds to run an asymmetrical campaign. With no need to build an organization or a ground game, or kowtow to interest groups, the challenger could run an inexpensive, streamlined campaign, focused on Trump’s points of weakness.

With Trump’s support among Republican women teetering, for example, the candidate could focus on engaging this demographic group. Similarly, the candidate could challenge Trump on policy issues such as the failure to repeal Obamacare, the pointless government shutdown, the inability to pass legislation funding the wall, the attempt to secure this funding through an extra-legal emergency declaration, and the ineffectual negotiations with Kim Jong-Un.

(2) Ideas can be wielded as potent political weapons. Buckley, the self-proclaimed long-shot candidate, focused on shaping the 1965 race and New York politics by churning out policy proposals. These included constructing widespread bicycle paths and other ideas that were subsequently implemented in New York City.

By producing proposal after proposal, Buckley drew the attention of his adversaries to him, and forced them to spend time responding to him on his own terms. According to one analysis of the race, “After mostly ignoring the Conservative candidate, both Lindsay and Democrat Abe Beame shifted their attacks to Buckley in the campaign’s final days.”

Given Trump’s temperament, he could well be drawn into a fight over policy and he has not, historically, been adept at such arguments.

(3) Even an unsuccessful primary challenge can help lay the groundwork for the future. In the end, Buckley’s predictions mostly held: Lindsay won the race with 45 percent of the vote, holding off Beame at 41 percent and Buckley at 13 percent. But Buckley changed the character of the election, and, in the long run, changed the character of the Republican party.

Losing to Trump will plant a flag for the post-Trump Republican party to rally around, because in the aftermath of Trumpism, the GOP will need to chart a new course for the future. It could even leave a challenger well-positioned for 2024, if they were so inclined.

To be sure, the 1965 New York mayoral race is not the 2020 Republican presidential primary. They differ in too many ways to count. But they are fundamentally similar in one very big, important sense: In both, the Republican favorite was highly imperfect and stood in opposition to mainstream conservative ideology.

Buckley understood that these two facts created room to run in 1965. And they’re creating room to run today.